He introduced Manual Vacuum Aspiration (MVA) in the whole of Africa, which changed management of abortions. Prof Khama Rogo considers it one of his greatest global achievements.

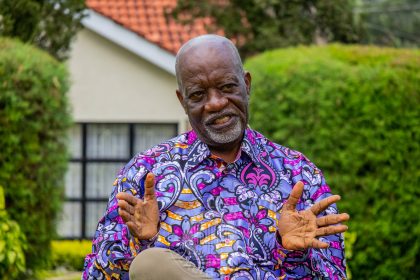

When a stout man sporting a box-cut hairdo opens the non-imposing black gate to a neat compound, a lean figure bending his 70s, receives the Willow Health Media crew at his home in Gem, Siaya County.

Today, Prof Khama Rogo is in a floral Mandela shirt, beige cotton pants, a baseball cap, and beige Sketchers that have seen better days on the road to the nearby Sagam Community Hospital, which he founded and funded.

Behind the simple mien lies a witty, restless bolt of energy whose achievements would drive some people to ostentatious lifestyles and self-destructive hubris. In case you’re wondering, Prof Rogo is the sibling of the late flamboyant politician and fashion icon, Orie Rogo-Manduli.

But at first sight, you will be forgiven for seeing in Prof Rogo, an ordinary pensioner who has kept himself well against the vagaries of success, maintaining a neatly trimmed circle beard and a KCD-registration Toyota Harrier.

As the interview progresses, you realise he would have no heartburn fueling a 5.7-litre, bi-turbo V-8 behemoth that has become a mobility uniform for Kenyans who “have been there”, but that’s not him.

Prof Rogo was Lead Health Specialist and Head of Health in Africa Initiative at the World Bank

For starters, Prof Khama Rogo is the universally recognised health systems consultant, reform guru, and restless warrior for health justice.

The professor in Obstetrics and Gynaecology holds a PhD in Gynaecologic Oncology from Sweden’s prestigious Karolinska Institute, where the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded in Stockholm.

That is not all.

For ten years, Prof Rogo was the Lead Health Specialist and Head of the Health in Africa Initiative at the World Bank Group, in charge of Public-Private Initiatives. Not to mention his transformative contribution to Kenya and Africa’s health sector.

Prof Rogo was head-hunted for the World Bank job, and “It took a lot of persuasion for me to leave. I didn’t go there for the money. I was fine with my clinic in Nairobi,” he says.

After he left the World Bank, it took four people to fit in his shoes, which is hardly surprising.

Indeed, his intellectual footprints are found in far-flung lands, the USA, India, Francophone and Anglophone Africa, as we found out during our eight-hour interview on his well-kept lawn, a venue we chose in preference to the neat gazebo that boasts a miniature bar from where the shoulders and neck of a Bacardi bottle peep at visitors. But we are not here for fun.

Oburu Odinga and brother, Raila, were older and ahead of him in primary school

Prof Rogo, we learn, was born in Kaloleni Estate in a “perfectly apartheid Kisumu” of the 1940s and 1950s when “Whites were first (class) citizens, followed by Asians and Somalis and ‘Africans’ third,” he recalls.

Oburu Odinga and his brother, Raila, were older and therefore ahead of him at Kaloleni Primary (for Africans only), and where his parents were pioneer teachers.

“Manyatta and Nyalenda were African reserves just like wildlife reserves, and you needed a pass to go to Kisumu. If you were found in Milimani, where white men lived, you were a vagrant.”

A white police officer would knock on doors at night looking for vagrants. If the door wasn’t opened by the third knock, he just kicked it open.

Kaloleni was tough with all manner of people, including the faithless and the tribeless. Lucky for little Rogo, in their household, “It was work, learn and pray. Our firstborn was Orie. We all knew how to cook. My chapati is as good as any girl’s. We were brought up equally.”

In Kaloleni Primary, the doctor in him manifested after being exposed to hospital dressers in their white uniforms. In his football team, he was always the “team doctor, treating” victims of vicious tackles and other injuries.

But it was at Dr Ochieng’s clinic in Kisumu where the medical bug planted its stingers. A young Rogo had delivered a letter from his father to Dr Ochieng, who was among the first Africans to graduate from Makerere with a medical degree, besides being a pioneer private doctor in the town.

Prof Rogo chose medicine as law, which his high school teacher recommended, was not challenging enough

Dr Ochieng looked at him and remarked, “I can see it in your eyes; you are a doctor, and it just entered my head that I would be a doctor.”

Rogo would later play for Kisumu Stars as a University of Nairobi first-year medical student.

This ended when, upon seeing a picture of him airborne while fighting for the ball with the legendary Kenya Breweries’ right winger Binzi Mwakolo appeared on the sports pages, Prof Joseph Mungai, who taught Human Structure and Walking, advised him to choose between medicine and football.

“On Friday, I was on an Akamba bus to Kisumu to play for Kisumu Stars with Bobby Ogola,” he recalls. This stressed his studies as he would catch the same bus at one O’clock on Sunday, arriving in Nairobi at 7 am for classes.

Rogo had no option. Medicine was not like Law, which his high school teacher, a Mr Taylor, had recommended, but he thought it not challenging enough.

“Passing exams was not a problem. I had a one [distinction],” he says, referring to his O-Level results at Homa Bay High School before proceeding to Duke of York School, now Lenana School, and then the University of Nairobi in 1973, where he says, “we were the best from East Africa.”

Other students juggled lab coats and football boots, which is how we had Dr William Obwaka and Dr JJ Masiga

At the university, things were harder than he had reckoned. “In the first year, you had to cram human anatomy and embryology. You enjoyed your Boom (student’s stipend) and realised how much you had missed once you were back in class. The first two years in medicine were the toughest, but rewarding.”

Later, other students would somehow juggle lab coats and football boots, which is how you had football stars named Dr William Obwaka and Dr JJ Masiga.

Rogo graduated in 1978, but not before traversing a rough patch as the chairman of the Association of Medical Students of the University of Nairobi, AMSUN. “I am still the chairman of the class 50 years later,” he says.

At the university, Rogo hadn’t decided whether he would be a physician or a surgeon, but he knew paediatrics was out for him.

“I didn’t like the way kids cried even when you tried to do the best for them.” So, he became an obstetrician-gynaecologist because it rolled a physician and a surgeon in one role.

He had noticed suffering at the infamous Ward 6 of septic and incomplete abortion patients

Prof Rogo would be the Medical Officer in charge of the Kwale District Hospital, but his passion for obstetrics and gynaecology found a home in Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), where he had noticed the suffering at the infamous Ward 6 of septic and incomplete abortion patients. It tugged at his heartstrings.

“You go to the theatre and find the suffering young girls and women coming in. You go to the theatre; you find the uterus is rotten. I said something must be done about it.”

Prof Rogo had also been disturbed by the high maternal mortalities at Kenyatta. The pathos and ethos that shaped his zeal to do the best are encapsulated in the stream of consciousness below:

“I loved saving lives. I have never seen a place where the lives you save become more immediate. Whether it’s a newborn or the mother. She is coming in; bleeding, collapsed. You resuscitate, you remove the placenta… sometimes it’s a placenta that is retained, and life just comes back to this person, and then there is the baby you struggle to deliver, and you do a caesarean section. He can’t breathe.”

Saving lives bestowed on Prof Rogo spiritual, moral and intellectual worth. “The rewards were very immediate and very real. Then they live to thank you. The “thank you” from a mother whom you have saved, and the baby is there. Those things just overwhelm you. And I said, ‘This is it.’ I said this is why I went to medicine, and reproductive health became my mantra.”

This method of terminating pregnancy using suction is done when the patient is awake

Armed with a master’s degree and now a university lecturer, the future professor vowed to transform Ward 6 from a place of suffering by replacing theatrical surgery with a technique called MVA, Manual Vacuum Aspiration.

This method of terminating pregnancy using suction is done when the patient is awake with a narrow tube attached to a syringe that is used to empty the womb using aspiration (gentle suction), according to one authority.

“It was battle royale,” he recalls, referring to the opposition of the potentially life-saving technique by the Catholic Church.

With Ward 6 ever full of incomplete septic abortions, and nurses incessantly bringing in more patients from casualty while others were recovering from anaesthesia, it was hell.

As a student in KNH, Rogo had once conducted 75 uterine evacuations from 8am to 8pm because, in his words, “the ward is full and is being filled every time from casualty, and you have to be in theatre because the women are brought in bleeding.”

With 100 patients and all that sepsis, Ward 6 was where medics were posted as punishment

“When I became a lecturer with knowledge about MVA, I said you didn’t have to be an MD doctor to do it. It could be done by nurses in a health centre. So, decentralise this thing so that people can be helped faster and closer to home. I demonstrated this at Kenyatta.”

Ward 6 was known for crowding, “with 100 patients and all that sepsis.” It was also the ward where you posted nurses and doctors as punishment.

“I said this is not right,” recounts the professor. “I said we will be having tea here, and it happened. I set a room aside for the MVA, and patients didn’t have to go to the theatre. We did it without anaesthesia because with MVA, the cervix is already open. You simply suck. You don’t scratch, and the woman walks home.”

Within a month, he had cleaned the ward and reduced the traffic and, more importantly, the suffering of patients.

It was an endeavour that won praise and condemnation, but he was ready. The Catholic Church was livid because Prof Rogo and his team were also offering post abortion and adolescent health counselling, which it considers antithetical to its doctrines.

Catholic Church head, Cardinal Maurice Otunga would write asking that Dr Rogo be fired

At the Consolata Kindergarten, Mother Superior tried to expel his youngest daughter, Paula, because of the “evil things” her father was doing at Kenyatta. That stopped after consulting his lawyers, Oraro and Rachier Advocates.

The head of the Catholic Church in Kenya, Cardinal Maurice Otunga, would write to the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Prof Nimrod Bwibo, asking that Dr Rogo be fired, only for the university to say no in recognition of his work at KNH.

Prof Rogo would introduce MVA in the whole of Africa, which he considers one of his greatest global achievements, “because it was a life-saving thing for everybody. It changed the way we managed abortions,” he says.

MVA would transform Mama Yemo Hospital in Kinshasa, Makerere, Muhimbili in Dar es Salaam and Black Lion Hospital in Ethiopia, to name but a few.

In recognition of his contribution to reproductive health in Africa, Prof Rogo would become the President of IPAS, Africa.

Prof Rogo traces endless doctor’s strikes to confusion from postgraduate medical training

With an expert on public health systems like Prof Khama Rogo, why does Kenya perennial face doctors’ strike?

Prof Rogo traces the confusion that arose from postgraduate medical training. He told Willow Health Media that Kenya once had a postgraduate fellowship arrangement with the UK, but it could not absorb all the medical graduates the country was producing.

The solution was to train the masters’ students at the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), which was easy as the University of Nairobi was the only one producing doctors. But, with time, some students started sponsoring themselves. This increased the number of master’s students, a situation that worsened with the advent of devolution: doctors employed by counties enrolled for post-graduate training, meaning they were working for KNH but were not its employees!

Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) was also training and using post-graduate medical students, thus denying the counties more medical experts.

“Who is supposed to promote them? KNH? the county governments? Or the Ministry of Health?” wonders Prof Rogo, hinting at this confusion as one of the causes of Kenya’s perennial doctors’ strikes.

Decentralise training of postgraduates to county hospital-based colleges

“Where’s the vision when KNH says it doesn’t know what 500 University of Nairobi M.Med students do there?” he wonders, adding that a similar number could be at MTRH.

The solution, says Prof Rogo, is simply administrative and not budgetary: Decentralise training of postgraduates to county hospital-based colleges, and voila, the counties will have the white coats at their disposal instead of paying the underworked lot concentrated in KNH and MTRH.

Master’s degrees in medicine aside, Prof Rogo is full of praise for our Medical Training Colleges, for which he reckons “Kenya should get the Nobel Prize because globally it’s (the MTC approach) the single most effective, low-cost production of mid-level health workers anywhere in the world in the history of medicine.”

These Medical Training Colleges are the reasons why Kenya doesn’t have a shortage of health technicians like radiographers. “They have tried it elsewhere, but it’s all fragmented.”

The problem with MTCs currently is that every MP using them to hunt votes by wanting at least one in their constituencies, regardless of the quality of equipment, facilities and training.

Mushrooming medical Training Colleges offer so many diluted courses

“They have been politicised from 20 to 87. Now they are worse than my local primary school here,” laments Prof Rogo.

No serious thinking and planning is going behind the mushrooming of the MTCs, which he says, “Offer so many diluted courses.” He blames the mess on their licensing not being done by the Medical Council or the Nursing Council of Kenya, but by the Commission for University Education.

His take on MTCs pans to the general training of health workers in Kenya, where “People are graduating without degrees. They only appear at graduation ceremonies,” he says.

Now, how on earth is this possible? “There is no indexing of medical students. Nobody has given the number of medics under training, who will graduate, and when they will do so.”

He says the Ministry of Health has been resisting the indexing of students training abroad.

“How do you pay salaries yearly to people you claim you don’t know how many there are and say you don’t have money for interns?” he wonders.

Medical internships is just another cog in MOH’s confused gearbox

Talking of internships, it turns out, they have become another cog in MOH’s confused gearbox. Initially, the internship was only for doctors, but now there are 43 recognised cadres, while the number of health courses is about 100, meaning the courses are more than the cadres.

“This is why you have ridiculous degrees such as a B.Sc. in Paramedicine.”

And it gets worse. The unrecognised cadres, it turns out, have trade unions, while some colleges don’t offer practicals, telling students that bit will happen during internships!

Prof Rogo believes the problems bedevilling Kenya and Africa’s public health sector have little to do with budgetary allocations, but rather, baffling inefficiency, wastage, lethargy and graft.

Here is how, in the professor’s books, the non-budgetary foolishness is killing Kenya’s health sector and what better way to shine the torch on the swamp through the comedy of errors at the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) in Nairobi.

KNH, explains Prof Rogo, swarms with hundreds of medical officers from the counties who are there for their postgraduate (master’s) studies.

This, he says, looks fine until “you realise the counties are paying salaries to doctors who are being underutilised in KNH and for an unknown period of time.”

Kenyatta National Hospital has 57 gynaecologists but only two theatres

Mandera has 39 doctors in training in KNH, and in the county, there are fewer than 10 doctors and a huge wage bill,” he illustrates.

Of the 600 consultants in KNH, 50 per cent are from the university, with the fees being paid by the Ministry of Health.

Again, this might sound terrific until the good professor tells us the humongous facility has 57 gynaecologists but only two theatres, meaning the fellows can only do two weeks’ surgeries in a year!

These were the findings of a task force Prof Rogo chaired, but which a court of law declared illegal.

In July 2024, President William Ruto appointed him to head the 20-member task force to audit Kenya’s health human resources, to identify the legal, policy, administrative and operational constraints impeding the performance of the health sector with regard to human resources.

But in February 2025, Justice Bahati Mwamuye ruled that the task force was illegally constituted and its recommendations [which, hopefully, would have drained the unhealthy swamp] could not be implemented. This, after the task force submitted its findings to the president.

If you want to thrive in Kenya, get posted to KNH, then do your thing

In the matter filed by the Law Society of Kenya, the judge held that the task force duplicated an earlier one set up in 2023 with a similar mandate.

Back to the underused doctors at KNH, he says: “This is why everybody is running their private clinic. If you want to thrive and do well in Kenya, get posted to KNH and do your thing”.

Things get farcical. The task force found two obstetricians posted to the hospital’s Spinal Injury Unit by the Ministry of Health. “Is it the patients who are fertile or the staff?” we asked. Mathari, a psychiatric hospital, they found, had its share of obstetricians, too!

You would think the KNH management is thankful that the free labour frees it to build more wards, replace tattered linen and have no patients sharing beds, if not sleeping on the floor.

On the contrary, Prof Rogo couldn’t believe his ears when the hospital’s management submitted to his task force that, as a parastatal, it needed billions of shillings to employ more doctors. Never mind the counties, and the University of Nairobi provide it with a thousand medics for free.

KU Hospital facilities are better than the Presbyterian Hospital’s in New York

Then there were the strange happenings at the Kenyatta University Teaching, Referral and Research Hospital, KUTRRH. Prof Rogo was a consultant and had recommended that running the Chinese-built turnkey hospital be contracted to private management, with the university doctors providing labour.

Repaying the Chinese loan wouldn’t have cost Kenya a penny if the hospital was run well, “but they chose the common African path, solutions that don’t help people who cannot afford services,” says Prof Rogo.

“I told them [government] to let the university use it as a teaching hospital and set the standards. The facilities were better than the Presbyterian Hospital’s in New York,” recalls the professor.

The recommendations were taken to President Uhuru Kenyatta, but certain forces “were more powerful,” he says.

Eventually, the Ministry of Health yanked the institution’s ownership from the Ministry of Education, kicking the university out of the hospital. Now, just like KNH, it runs as a parastatal under the Ministry of Health.

KU Hospital would have forced Nairobi and Aga Khan to slash charges

“They cut the university out of the hospital and started employing consultants. So the university lecturers are serving in Kiambu hospital while the [university’s] specialists can do nothing there, but the hospital (KUTRRH) is advertising for their jobs,” says Prof Rogo.

According to the professor, the services that the well-equipped KU Hospital would have offered at reduced rates would have forced Nairobi and Aga Khan hospitals to slash their charges to the benefit of Kenyans. Another wasted opportunity.

Prof Rogo has always been in high demand starting from when he was head-hunted for the World Bank job and “It took a lot of persuasion for me to leave. I didn’t go there for the money. I was fine with my clinic in Nairobi,” he says.

After he left the World Bank, it took four people to fit in his shoes, which is hardly surprising. In his “global hat” to borrow his phrase, Prof Rogo’s achievements speak for themselves.

He was once assigned to assess the entire health system of India. His unflattering report to the World Bank stopped a billion-dollar project “because they had cheated. People lost jobs,” he says.

However, the ultimate challenge was when the bank assigned him to develop a system for the world’s newest nation-state, South Sudan, which had been forged out of a 25-year-long civil war.

When a woman was in very prolonged labour, men would start digging her grave

It was as if God had granted him a wish to go to the Moon and start a new health system from scratch. “Sudan was a labour of love and passion to create a health system out of nothing. From zero to nothing,” he recounts.

“There was no health service apart from that at the garrison towns. When a woman was in very prolonged labour, men would start digging her grave,” he says of the country where he found the country’s first minister for health, a fellow that had been flown from refuge in Australia, sitting under a tree.

“No office, no nothing,” he recalls. “I moved him from the tree to a tent, to a container, to a prefab and then a ministry in two years.”

It was a South Sudan where NGOs had a field day running health camps on big money, fleecing donors to enjoy their weekends in Nairobi. This, happening when the world’s youngest nation-state, emerging from the ravages of 25 years of civil war, had only three medical doctors: Rogo himself, an anesthesiologist and the minister.

There was no bank, radio or telephone service, so when he organised the first health summit, planes chartered from Nairobi would fly to fetch ministers only to realise they couldn’t land in the bush.

Officials would collect bundles of notes to pay salaries. There was nothing like a Human Resource management system.

South Sudanese politicians lined their pockets with project funds

At one time, the rebel army stopped a consignment of drugs from entering the country via the Uganda border because it had not been informed.

It took a call from Prof Rogo, from Washington DC, to his former student, by then the minister for defence in Uganda, who ordered the army to escort the drugs to Juba.

The professor also recalls seeking the intervention of the World Bank boss in Ethiopia to explain to the Japanese government that South Sudan was a new state and therefore not subject to US-imposed sanctions against Sudan. That was after Toyota Motor Corporation had rejected an order for a fleet of Land Cruisers. The World Bank boss was Japanese.

His energies in South Sudan would experience setbacks as politicians lined their pockets with project funds. “As exiles in Kenya and Uganda, they had learned there was money in corruption,” he says.

Prof Rogo’s labour of love and passion would go up in smoke when the South Sudanese started their own civil war, destroying everything he had put in place.

Africa’s healthcare system is a story, not of scarce resources, but of plunder

But Kenya hasn’t been spared the wastage spree that grips African governments. Consider the case of how a plan to save Kenya’s public hospitals with modern, leased medical equipment was instead sabotaged by the very leaders tasked with its success.

Prof Rogo says Kenya’s Managed Equipment Services (MES), was a Public-Private Partnership in which the Ministry of Health contracted private sector providers to supply, install, maintain, and replace equipment in public hospitals.

It was meant to rid Kenya of the eyesore of unused or misused medical equipment rotting in “boxes that had never been opened or had been rained on under leaking roofs.”

Prof Rogo reasons, had the same equipment belonged to the private sector, they would have taken care of it, driven by business and reputational grounds.

“In the West, they lease functionality. You are guaranteed 80 per cent uptime, and the provider replaces equipment when it breaks down; they can repair it within 24 hours,” says Prof Rogo.

But some people in the Ministry had other ideas.

Once the equipment was supplied and installed, big shots at Afya House and governors rejected the free equipment monitoring system for the machines from the suppliers, General Electric Corporation (GEC) and Toshiba. The system would indicate the equipment’s state anytime, including when it was repaired, by whom, what was replaced, and the cost.

New linen had been stored for display as patients froze in hospital wards

GEC was offering free training for health technicians in its Karen nerve centre in Nairobi. Governors didn’t want the equipment because it was contracted by the Central Government, denying them a lucrative rent-seeking opportunity.

Afya House, therefore, brought in a middleman who can never be cheaper than the manufacturer. The new kids on the block would lease everything, cutlery included.

“We create our failures,” says Prof Rogo, who lists his saddest memories as including visits to Mali, Mauritania and other Sahel countries where bands would play guards of honour and brass plaques mounted on walls during opening ceremonies.

Days later, the fresh linen would be transported back now that nabobs from government had been flown back to the capital, never mind the new linen had been stored for display as patients froze in the wards.

Prof Rogo remembers Tanzania’s first President, Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, telling him how he enjoyed retirement because, after decades, his nostrils were not being assailed by the smell of fresh paint, opening institutions that were of little use to the ordinary Tanzanian.

Prof Rogo also recalls a time when AMREF was the only health NGO, and medical workers met in Special Health Sector Training Institutes, SHSTIs.

Divine interference saw them being awarded a Sh30 million contract

“We didn’t go to hotels,” he says, arguing that the huge amounts spent on hotels should be spared to revive and expand the SHSTIs. But this disease is incurable, as “The KNH board”, he says, “prefers to meet at the Silver Springs Hotel as its boardroom lies idle.”

So, is Africa condemned to live or die from a sick public health sector for good?

“Until this DNA of corruption is wiped out, the health sector will suffer,” he says, falling short of recommending the physical annihilation of the corrupt and their networks, the way Jerry Rawlings did in Ghana.

“The sacrifices we need for a new beginning are more painful than we can contemplate,” he opines. Juxtaposing the solution to the problem, he cites the case in Kenya where somebody told a parliamentary committee of a divine interference that saw them being awarded a Sh30 million contract to supply medical equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In a country he wouldn’t name, donors funded the importation of condoms to stem the spread of HIV-AIDS, but bureaucrats had other ideas. A close inspection of the consignment revealed cartons full of Viagra instead of the rubber sheaths.

Prof Rogo has seen over 30 delegations from Africa coming to learn the magic of NHIF, only for corruption to torpedo the hospital insurance fund.

He says the beauty of the defunct NHIF lay in focusing on the household “because poverty is a household thing in Africa, unlike in the West.”

An audit would discover that NHIF had settled claims involving male pregnancies

He has witnessed strange things at the Linda Mama Initiative, which was initiated by former First Lady Margaret Kenyatta.

“It covered the pregnancy but not the household. If the money that went into Linda Mama was used to cover the indigent, we would have been on our way to Universal Health Care,“ he says.

Indigents refer to people who are financially unable to afford basic necessities.

In the first year, he says, the money did not go to NHIF, which was pressured to settle claims on the promise that it would be compensated by the Treasury. This didn’t happen, throwing the Fund into a financial crisis. An audit would discover that NHIF had settled claims involving male pregnancies!

“How Kenyan men started delivering, we could not explain to the World Bank side, but we told them men are unique in Kenya.”

Next in the list of infamy was Edu Afya, the now-discontinued Sh4-billion medical insurance scheme for secondary school students.

Donor health workshops biggest cause of absenteeism in the health sector

An illustration of misplaced priorities, Edu Afya forgot that the demographic it was covering was the healthiest, as it left the ailing and ageing vulnerable segment of the population to bear the brunt of sickness.

Prof Rogo could give more depressing examples, including Kenya’s donor-driven health workshops bonanza, which he says is the biggest cause of absenteeism in the public health sector, as doctors and administrators cash in on a per diem frenzy.

“Some ‘attend’ as many as three workshops a day. All they need is to sign forms. Some are paid for 600 days in a year,” he says.

But why would anyone allow this profligacy? Because, Prof explains, donors say nobody would bother to attend the policy-generating workshops without per diems.

Prof Rogo is persuaded that the despicable state of public health services in Kenya has little to do with financial allocations.

There is not a single thing Nairobi Hospital can do that KNH can’t

“The combined budgets of the three leading hospitals, KNH, Moi and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral hospitals are bigger than what we give to all counties on top of the money they collect,” he argues, wondering why such institutions cannot offer world-class health services.

“There is not a single thing that Nairobi Hospital can do that KNH can’t,” he says, explaining that the biggest driver of healthcare costs in Africa is not high charges by private hospitals but the dysfunctionality of the public sector.

“If KNH can do renal transplants correctly, Nairobi Hospital will drop charges,” he argues, citing the dropping MRI charges in private hospitals when the government introduced the Managed Equipment Scheme.

No wonder Prof Rogo has predicted that debate on the health sector in Africa will soon determine the presidency, because you cannot hide disease.

“If you are coughing now and we don’t tell you it’s TB, it doesn’t disappear”.

Our last question: Is the professor worried that he has made enemies because of his outspokenness about graft and inefficiency in the public health sector?

Not really!

“I’m in my turf. I only comment on health. In health, I’m safe. I will say it; I will defend it. I will talk about my village, my country and my continent. It’s easier to defend the truth than to defend lies because it’s very difficult to remember what the last lie was. I’ve kept my linkages, my sanity and most importantly, my integrity.”

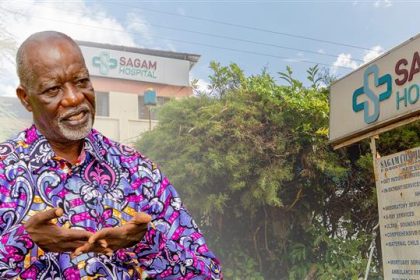

He built Sagam Community Hospital with own resources in memory of his father

At this point Prof Rogo walks the Willow Health Media team to the Gordon Rogo Memorial Sagam Community Hospital, which he built with his resources in memory of his father, greeting villagers and exchanging pleasantries.

“When you are walking to the hospital, you are also walking through your village. You greet every woman, every child,” he says, adding that he finds tranquillity in the daily rhythms of the village.

The germ seed for Sagam Hospital, we slowly learn, was planted many years ago when Prof Rogo’s grandmother, Kezia, was down with pneumonia, but she was told the only available antibiotics at the local government health facility were reserved for the more vulnerable children.

“She told them ‘thank you’, went home, covered herself with a blanket and died,” recalls Prof Rogo, voice unmistakably melancholic.

A similar episode of neglect would play out when he took an old man with a broken hip to Siaya Hospital, where he left him on the floor because the beds were full. Weeks later, he returned only to find the man suffering on the floor. He couldn’t bear it anymore.

“I said ‘never’. If the government can’t, I will do it” and after the community cleared the bush, up came the Gordon Rogo Memorial Sagam Community Hospital in 1998.

I would rather be unhealthy living in a healthy community than being healthy in a community of unhealthy people

“I used my resources,” he says, adding, “I would rather be unhealthy living in a healthy community rather than being healthy in a community of unhealthy people. Sagam is my proudest achievement, not the World Bank jobs,” says Prof Rogo, who finds therapeutic beauty in doing good. Something money can never buy.

“When people around you are healthy, they can take their kids to school. Everybody is happy; the quality of life changes for everybody. You start being happy in the village. The joys of life stop being material possessions. Countries develop because there are people who work for the benefit of the people,” he reasons.

Sagam is a no-frills community hospital off the Luanda-Siaya Road, but it trains post-graduate M-Med students from Maseno University.

“Excellence is location-neutral. We do total hip replacement under spinal anaesthesia, and people walk home four days later. Caesarean Section is so easy. You can do it on that table,” he says, explaining that medical outcomes are important than equipment and sophistication.

Sagam handles over 50 patients, admits over 30 and performs about six surgeries daily

“Did you know that the operating theatre is the most unused space in African hospitals, yet it is the most expensive space per square foot because it houses the most expensive equipment?” we are informed.

When we visit the two-floor hospital, we meet Prof Rogo’s brother, also the chair of the 100-bed, squeaky-clean facility, who had his hip replaced there. Three women are waiting at the reception as a baby sleeps on a seat, while a smiling Dorothy waits for us at the reception.

Outside the ground floor, three new mothers exchange banter in the sun as clean sheets flutter in rhythm to the chirping of weaver birds.

Sagam handles over 50 patients daily, admits over 30 in the same period and performs an average of six surgeries daily. Its X-Ray, Ultrasound, Endoscopy, and Colonoscopy units run smoothly, our guide says.

Few people walk their talk, translating passion into action that, in turn, produces a tangible, touchable, viable and measurable outcome as Prof Khama Rogo has done in the medical field.