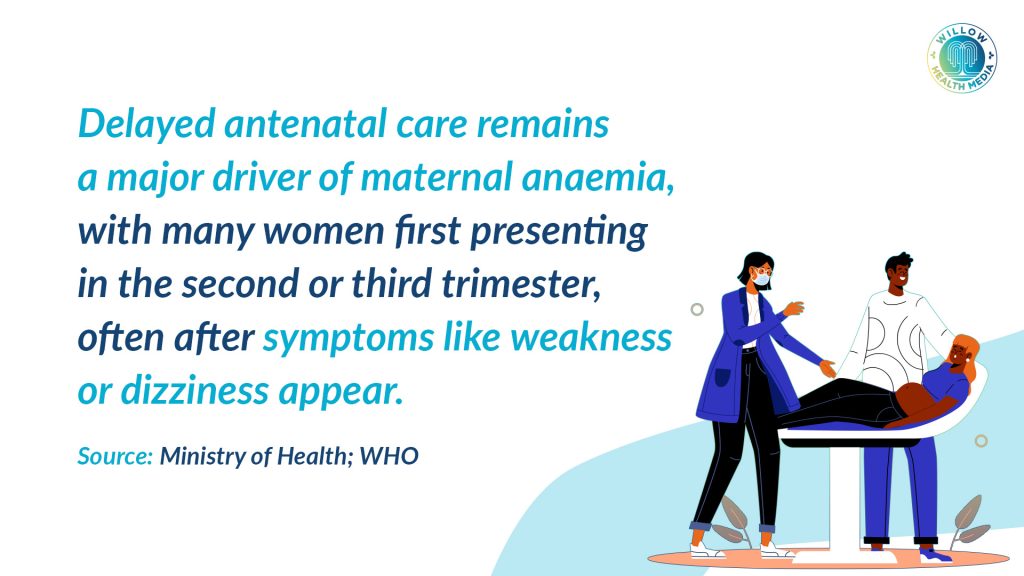

‘Most women don’t even know they are anaemic until they start feeling weak or dizzy,” says Nancy Gichana. ‘Some wait until five or six months to visit a clinic, thinking it’s too early, or they have no transport.”

When 19-year-old Amanda Ayuma became pregnant in October 2024, maternal anaemia struck within weeks. “I was so nauseous, I wasn’t eating, I couldn’t even drink water,” she recalls. Doctors diagnosed anaemia and prescribed iron and folic acid tablets, then Ranferon syrup when her condition didn’t improve. Yet by her due date, her haemoglobin was still at a concerning 9.2.

At Kangemi Health Centre, health workers referred her to Pumwani Hospital in case she needed a transfusion during delivery. “In case of excessive bleeding, they could not manage it here,” she explains. Though her delivery was safe, the experience left her shaken. “I felt dizzy most of the time. I ate greens and fruits daily, but nothing changed.”

Amanda’s mother, Rachel Afundi, is a Community Health Promoter (CHP) in Kangemi who had also experienced anaemia during pregnancy. She now guides her daughter and other women on a condition she sees repeated across the settlement.

“Many pregnant women are anaemic, but they don’t know it,” Afundi says. She believes the root cause often lies in food insecurity.

“Some haven’t tasted a fruit for two months. They just drink tea because they can’t afford food.” Her advice is practical: “If you can’t buy meat, eat greens and fruits available in the market.”

Some husbands refuse to give money for supplements or hospital visits

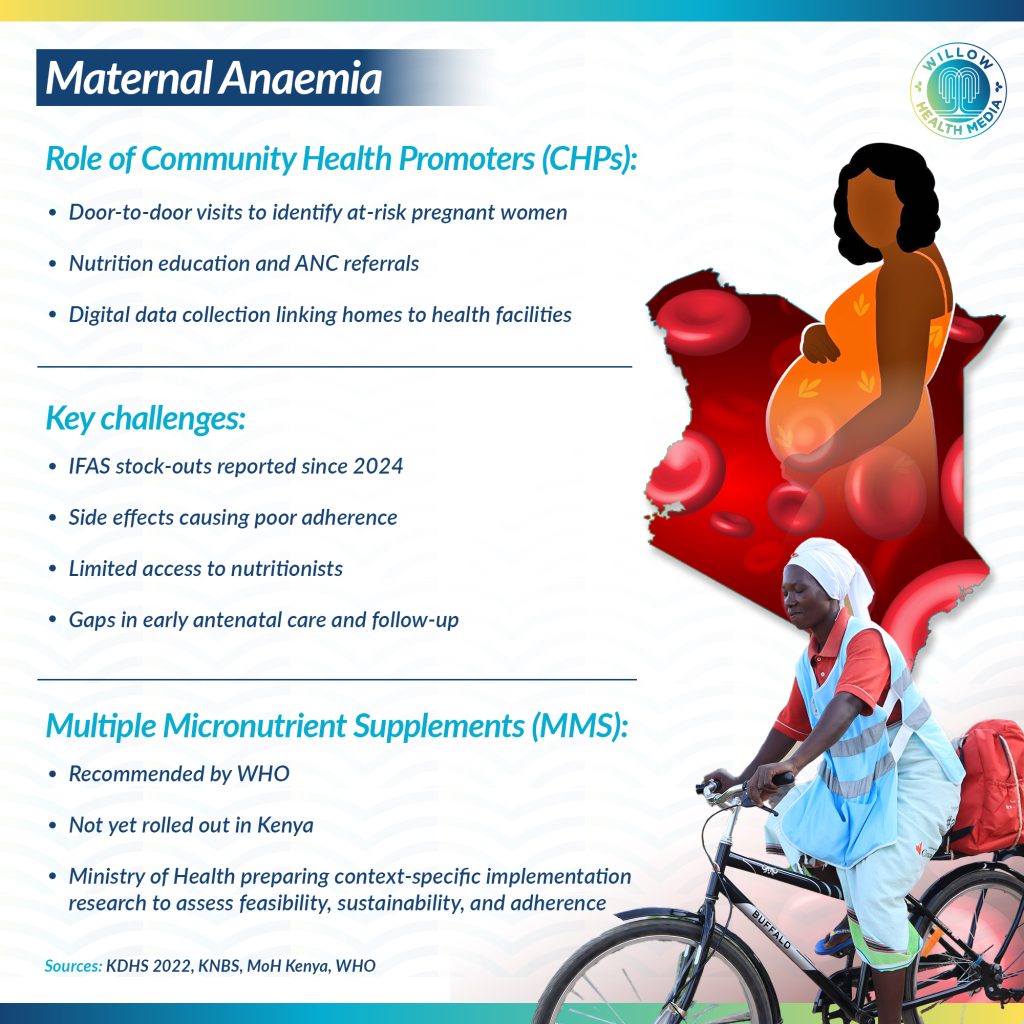

Like Afundi, CHP Nancy Gichana works door-to-door in Nairobi’s Kangemi area, educating expectant mothers, identifying risks, and connecting women to care.

“Most don’t even know they are anaemic until they start feeling weak or dizzy,” Gichana observes, “but some wait until five or six months to visit a clinic, thinking it’s too early or they have no transport.”

She also confronts deeper social barriers.

“Some husbands refuse to give money for supplements or hospital visits. Some teenage girls hide pregnancies until it’s too late.”

In 2023, Gichana worked with the Centre for Rights Education and Awareness (CREAW) under the Engaging Men and Boys program to encourage men to support their pregnant partners. “When men understand the risks of anaemia, they become more supportive,” she notes.

This community-level work is a critical part of the national strategy. Dr Flaviah Ogutu, a gynaecologist, underscores the importance of this early, community-driven intervention. “Coming to clinic within the first three months is where prevention begins,” says Dr. Ogutu, adding that CHPs are vital in emphasising the importance of supplements and early antenatal care.

At the Tassia Kwa Ndege Hospital, nurse Vivaline Odhiambo sees the impact of CHPs firsthand. Antenatal clinic attendance at her facility has risen to 75 per cent, and monthly deliveries have nearly doubled.

“Community health promoters have helped by visiting homes, encouraging women to attend clinics early,” she says. Vivaline’s routine involves checking for the subtle signs of anaemia-pale lips, tired eyes, brittle nails-before sending mothers for haemoglobin tests. “Anything below 10 is worrying,” she explains. “She needs urgent management to be safe by the time of delivery.”

Sometimes we get 100 doses a month, then 112 mothers turn up

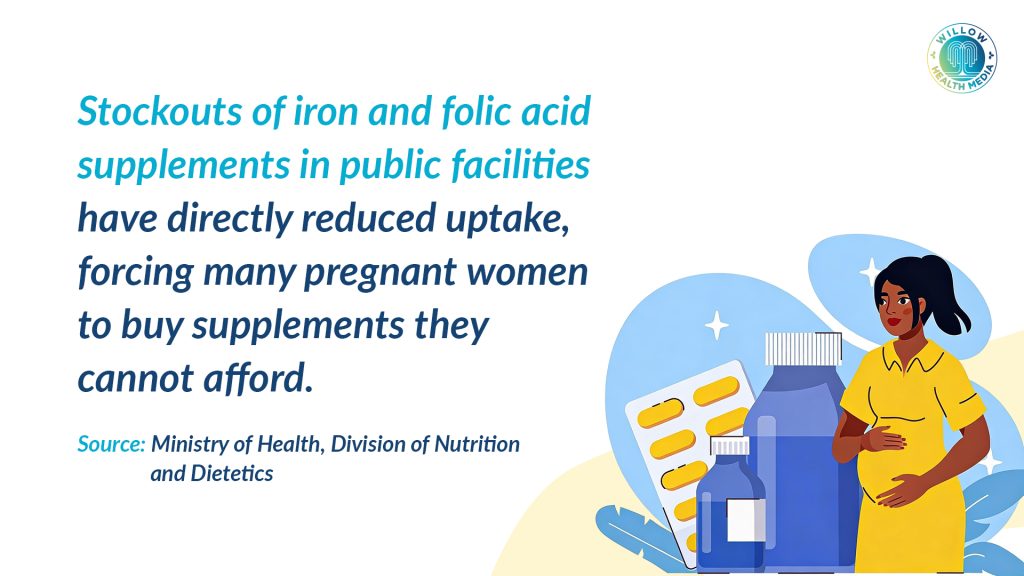

The formal healthcare system, however, faces its own severe challenges. The solution should be simple: providing free Iron and Folic Acid Supplements (IFAS) at public clinics. But shortages are frequent. “Sometimes we get 100 doses a month, then 112 mothers turn up,” Vivaline says. “When drugs run out, we tell them to buy, but many can’t afford them.” This gap in supply is a known issue.

Julia Rotich from the Ministry of Health’s Division of Nutrition and Dietetics confirms, “Stockouts started last year and were reflected in reduced uptake.” She notes that counties are now working to stabilise supply through their own procurement systems.

To strengthen the frontline response, the Ministry of Health has equipped CHPs with digital tools to track pregnant women and children under five in real time. “They form a critical link between the community and health facilities,” Rotich explains. “Through their data collection and education efforts, we get real-time information that helps shape our interventions.”

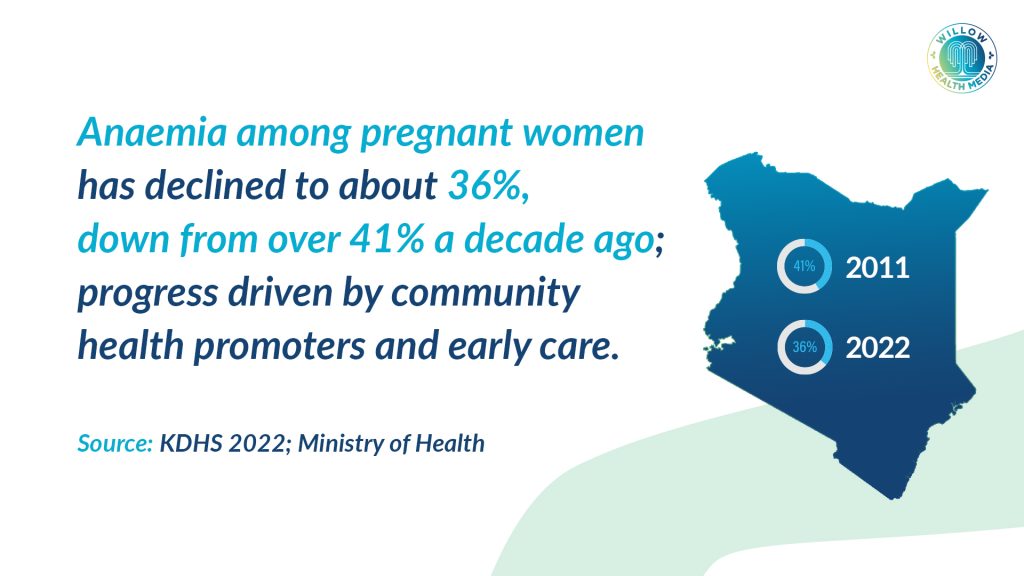

Despite the obstacles, the relentless work of CHPs in communities, coupled with policy efforts, is yielding cautious optimism. Rotich points to encouraging data: the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS 2022) shows about 36 per cent of pregnant women in Kenya are anaemic, an improvement from 41.6 per cent in 2011.

“We’ve seen a gradual decline in anaemia and improved uptake of supplements,” Rotich says. “With stronger policies, research, and community engagement, Kenya is moving closer to containing maternal anaemia.”

Graphics by Arthur Mbuguah.