Men at the coast culturally never got involved in Kangaroo Mother Care, but elders, health workers and door-to-door education and public campaigns are gradually changing attitudes, practices and outcomes.

Kennedy Garero gently carries his two-year-old daughter, Nelly, close to his chest in Kwa Mbaji village, Rabai, Kilifi County. For Garero, every moment feels miraculous-she weighed less than one kilogram at birth.

“Whenever I am home and not at work, I enjoy her company so much,” he says, smiling. “She is a miracle.”

His wife, Mgeni Mbaji says, “Their relationship is so special, sometimes I feel like I am the third wheel.”

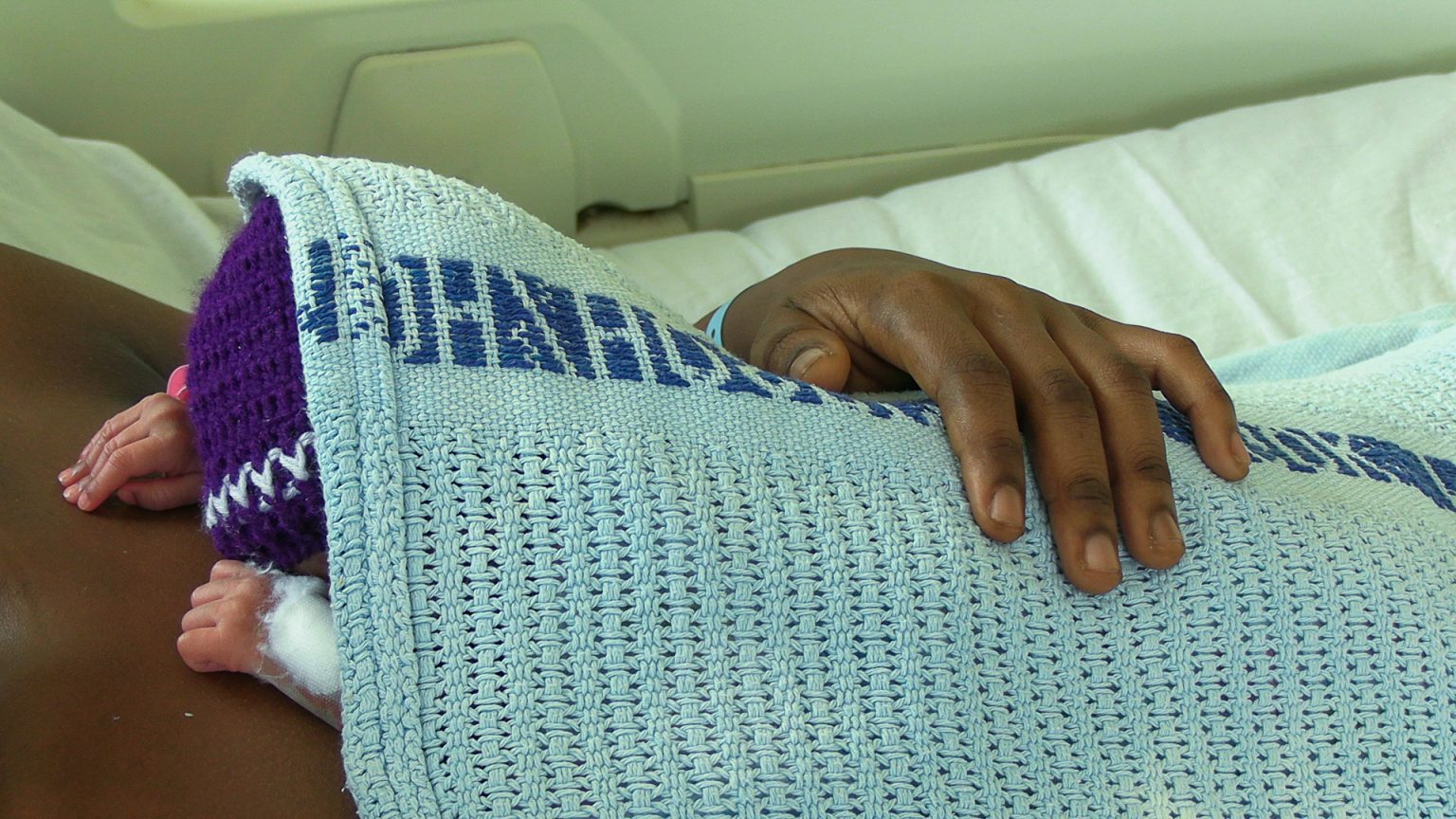

The deep bond between father and daughter was shaped in the neonatal ward through sleepless nights, anxiety, and Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC)-a simple yet life-saving method that places a premature baby skin-to-skin on a parent’s chest to keep them warm, support feeding, and protect them from infections.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends KMC as the standard of care for stable preterm and low-birth-weight babies. Studies show it can reduce newborn deaths by up to 40 per cent while lowering rates of hypothermia and infections.

For the Gareros, KMC not only saved their child’s life but also redefined fatherhood.

Kenya’s neonatal mortality rate is 21 deaths per 1,000 live births, with prematurity as a leading cause

Kenya records an estimated 12 per cent to 13 per cent of babies born prematurely, according to the Ministry of Health’s Kangaroo Mother Care Clinical Implementation Guidelines 2023. Complications from preterm birth are a leading cause of newborn deaths.

Kenya’s neonatal mortality rate is 21 deaths per 1,000 live births, with prematurity as a leading cause, according to the KDHS Report 2022. The Sustainable Development Goal 3, 2030 target is to lower this to below 12 deaths per 1,000 live births.

Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest neonatal mortality rate at 27 deaths per 1,000 live births, representing 43 per cent of global newborn deaths, WHO notes.

Mgeni’s third pregnancy felt relatively smooth. She attended antenatal clinics early, determined to do everything right.

One night, she noticed a watery discharge. Unaware that her amniotic membranes had ruptured prematurely, she planned to raise it at her next clinic visit, but alas! she went into labour that same night, and she was rushed to Rabai Sub-County Hospital, less than two kilometres from home.

Her daughter weighed 800 grams -like two loaves of bread- and “she was very transparent.”

Given her medical history, including previous Caesarean section and complications, health workers referred her to Kilifi County Referral Hospital, where “I started bleeding, but the doctor kept assuring me that everything was under control.”

She arrived around 2am and “The doctor told me I would deliver in about an hour,” but when her daughter was born, joy was mixed with fear as she weighed 800 grams and “she was very transparent,” Mgeni says. “Her skin was so thin you could almost see her inside. It was scary.”

Her baby was immediately admitted to the neonatal unit, where for two months, health workers taught Mgeni about preterm and low-birth-weight babies-how fragile they are, how easily they lose heat, and how critical warmth, feeding, and infection prevention are to survival.

Garero struggled to balance work, finances, and family. Travelling from Rabai to Kilifi Hospital could cost up to Sh1,000 per trip, and “When I didn’t go, I was in agony. But we communicated constantly.”

But gram by gram, her daughter gained weight. By 1.5 kilograms, she was stable enough for discharge for Kangaroo Mother Care to continue at home, where her hubby became an active partner, though traditionally, Mgeni would have repaired to her parents’ or in-laws’ home for postpartum care.

Some people said the daughter was born prematurely because of witchcraft

“We made this child together,” explains Garero. “I had to be there for her bonding and growth”, as they practised KMC at home, where “There were moments of disagreement,” he admits. “Sometimes I felt my wife was not following the doctor’s instructions exactly. But we would talk, solve it, and continue.”

Today, Nelly is a healthy toddler- playful, strong, and deeply attached to her father. But not everyone in the community understood their journey as “Some people said the baby was born prematurely because of witchcraft,” says Mgeni. The couple ignored the whispers as “We knew the truth,” Garero says. “We focused on our child.”

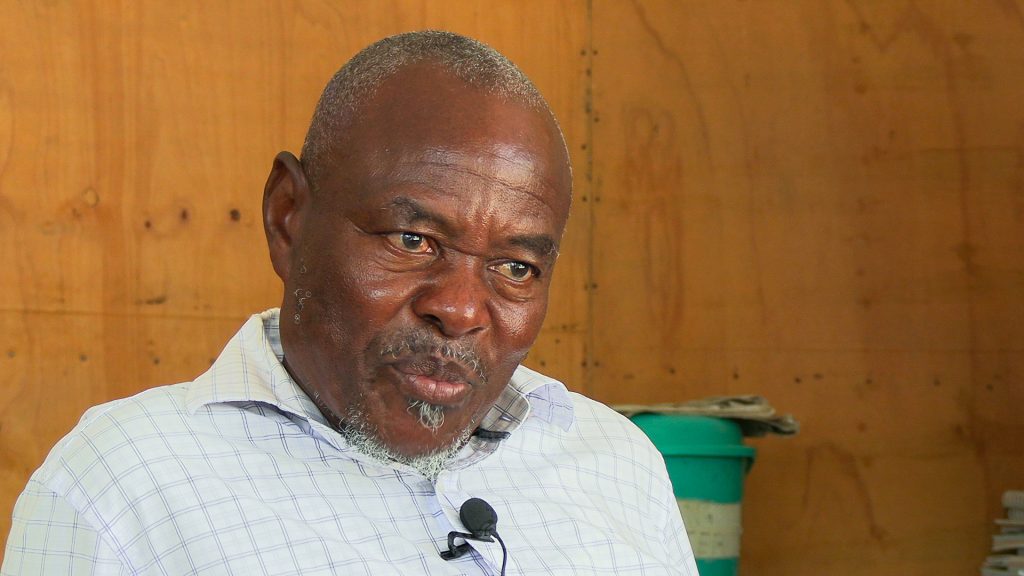

Jack Tsuma, a village elder in Rabai, says such myths are common, as “Some people associate premature birth with curses or chira (juju). But those are just myths and misconceptions.”

What is changing, he notes, is the role of men who previously left everything to women and “A pregnant woman would do all the work, even things that could harm her and the baby.”

Through door-to-door education and public barazas, elders and health workers have changed attitudes.

Men are now accompanying wives to clinics, which is a good step for child wellbeing

“Before, if a child was born prematurely or with a disability, the mother was blamed,” Tsuma says. “Now men are accompanying their wives to hospitals and clinics. That is a good step for child wellbeing.”

Mama Zipporah Mdzomba Mangi, a former traditional birth attendant and now a Community Health Promoter for nearly 20 years, stopped conducting home deliveries in 2003.

“In those days, there was no Kangaroo Mother Care,” she recalls. “There was no guidance on how premature babies need to survive. Many of them died.”

At the time, there were no clothes for children born very small and newborn clothing was regarded as a luxury. “Even small babies had nothing fitting them,” she says. “They were just wrapped in old blankets”, but today, she helps mothers follow KMC guidelines at home.

Mama Alice Mnyazi Mumba, another former TBA and CHP, agrees that it was through sheer luck that a woman gave birth to a healthy baby, as “There was no proper care. A mother could bleed, a baby could be in distress, and you would lose both in your hands.”

Common causes of preterm births include pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, and premature rupture of membranes

Cultural norms kept men away from childcare, “But now, with education and technology, fathers are more involved,” she says. “They attend clinics. They want to know, this is a digital generation.”

Kenneth Chiringa Madziwe, a long-serving CHP, says now men are involved in Kangaroo Mother Care, and he insists on educating both parents during home visits as “Bonding is for both mother and father,” he says. “Culture kept men away before, but that is changing nowadays.”

At Coast General Teaching and Referral Hospital, Dr Faiza Nassir, an obstetrician-gynaecologist and Head of Reproductive Health, says, “A preterm baby is one born before 37 completed weeks”, while “a baby weighing less than 2.5 kilograms has low birth weight.”

Dr Nassir sees eight to 10 preterm deliveries daily, with common causes including pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, and premature rupture of membranes, forcing doctors to deliver babies early to save both mother and child.

Preterm babies, she says, “Face problems with temperature regulation, feeding and infections” and hospitals use incubators and warmers to mimic the womb and Kangaroo Mother Care when they stabilize as it “supports warmth, feeding, bonding, and reduces infections.”

Hypothermia is one of the biggest threats but Kangaroo Mother Care is saving many babies

Elizabeth Njeri Kariuki, a neonatal nurse at Coast General Hospital, where she says, “I was born premature” and she’s now determined to help babies like her survive. “The smallest baby we have handled was about 400 grams,” she says. “Unfortunately, due to complications, the baby died after 10 days.”

Hypothermia is one of the biggest threats but “Kangaroo care is saving many babies,” says Kariuki. “Each baby has their own milestone. Some stay for up to three months in the unit.”

The hospital has a dedicated KMC room where mothers practice full-time care. Cultural misconceptions remain a problem as some mothers fear carrying their babies full-time could lead to ‘kuzoea mikono’, which is a misconception and “I encourage KMC as it helps in baby rapid growth and stability,” she adds.

Financial constraints limit father involvement, especially for families referred from distant counties. “But when fathers are present, the support makes a big difference,” she adds.

In the KMC ward, Mejumaa Kombo cradles her baby, born at seven months, weighing 1.6 kilograms, but who has since improved after referral from Tudor Subcounty hospital.

Sharlette Kahindi gave birth to twins, lost one baby, but refuses to give up on the other. “My baby was born at one kilogram,” says Kahindi. “Now there is so much improvement after three weeks.”

For her, Kangaroo Mother Care is not optional. “It is the best thing for my baby” and fathers like Garero slowly stepping into spaces once considered off-limits is redefining presence, warmth, and shared responsibility.

From Grams to Kilos: How Kangaroo Mother Care is saving Kenya’s smallest fighters

Both at the coast and in western Kenya, families say the same thing: prolonged skin-to-skin contact, a low-cost, evidence-backed intervention, is helping tiny infants grow from grams into kilos, even in settings where incubators and resources are scarce.