January 2025 marked a turning point after USA, the largest international donor to the HIV response, temporarily zipped its wallet.

When donor funding from the USA dried up early this year, the signs of collapse were immediate. Clinics closed quietly. Outreach vans stopped appearing in villages and informal settlements. WhatsApp groups once buzzing with reminders about support groups and ART refills fell silent. Outreach teams, many of whom had spent years building trust with the most vulnerable, were dismissed by text message.

For many people living with HIV, especially those in rural and marginalised communities, the sudden disappearance of services felt like the world had turned its back on them.

In Kenya, programmes focused on key populations stopped almost entirely. Nigeria saw at least five clinics serving key populations close, while Uganda experienced disruptions in nearly half of all such programmes.

Across several countries, harm reduction services were severely disrupted, with 77 per cent of programmes reporting major interruptions. The consequences have been immediate: hostile attacks and harassment of key populations have risen, according to community organisations.

“This is an attempt to erase our existence,” says Jeffrey Walimbwa of Ishtar MSM, a Nairobi-based organisation serving gay men and men who have sex with men, as captured in the UNAIDS 2025 report.

“There is a lot of fear because people are not sure what is happening.”

‘I thought I was going to die,’ says a 37-year-old sex worker and mother of three

For those dependent on these services, the ground seemed to shift beneath them.

“I thought I was going to die,” says a 37-year-old South African sex worker and mother of three, who requested anonymity, told the UNAIDS team during compilation of the World AIDS Day 2025 report.

For four months, she could not access the antiretroviral therapy (ART) that keeps her alive. “All I could think about was my kids.”

Her experience is far from unique. Across dozens of countries, abrupt cuts in international funding have pushed the global HIV response to the brink. The World AIDS Day 2025 report by UNAIDS delivers a stark warning that sudden disruptions in funding now threaten to undo years of progress made and put many lives at risk.

At stake is more than the global target to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. It is about whether millions of people, already living on the margins, can hold onto decades of hard-won progress.

About 31.6 million people were on lifesaving HIV treatment

By the end of 2024, the world was making steady, if uneven, progress. New HIV infections had fallen by 40 per cent since 2010, and deaths from AIDS had dropped by more than half.

About 31.6 million people, which represents about three-quarters of all people living with HIV, were on lifesaving treatment. Much of this fragile success was built on a combination of domestic investment and massive international funding, led by PEPFAR and the Global Fund.

Clinics in East, Southern and West Africa, Southeast Asia, and parts of the Caribbean were among the first to feel the impact. Frontline health workers were laid off. Community-led programmes were forced to close abruptly.

“The vulnerable populations we take care of do not trust our services anymore,” says Byrone Chingombe of the Centre for Sexual Health and HIV/AIDS Research in Zimbabwe. “They say, ‘You went away without notice.'” The cuts coincided with a projected 30–40 per cent drop in global aid for health in 2025, compounding the crisis.

Stock outs of condoms, HIV test kits, treatments for STIs

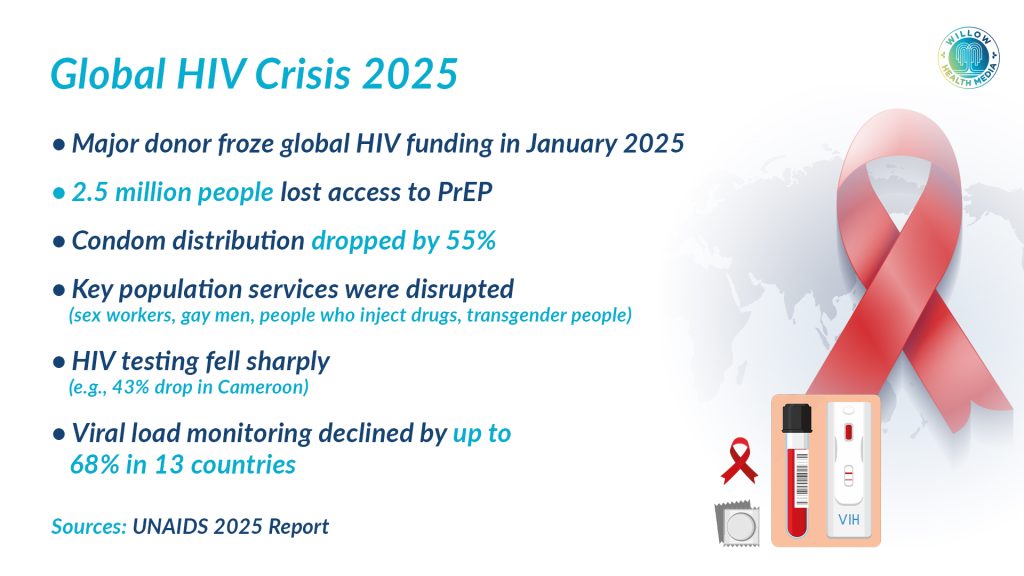

Prevention services absorbed the deepest blow. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) saw catastrophic declines. By October 2025, an estimated 2.5 million people who used PrEP in 2024 had lost access.

In Burundi, PrEP uptake fell by 64 per cent. Uganda recorded a 31 per cent decline, and Vietnam 21 per cent.

Other critical prevention tools also became scarce. Nigeria saw a 55 per cent drop in condom distribution, while Uganda experienced shortages of HIV testing kits. Botswana reported widespread stockouts of condoms, HIV test kits, and treatments for sexually transmitted infections.

The sudden collapse of the DREAMS programme was particularly devastating. “These programmes empowered me and transformed my life,” says Talent Manyoni, a young woman from Zimbabwe.

She lost access to accurate HIV information, sexual and reproductive health services, and educational and livelihood support. “I have witnessed firsthand the positive impact they have on young people’s health, confidence, and future prospects.”

A young woman in Kenya lamented ‘we were safe before, now we are left alone’

“Social support networks have been weakened,” says a Ugandan peer educator. “Thousands of girls are now isolated.” A young woman in Kenya described the closure as “hopeless. We were safe before. Now we are left alone.”

Across Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America, key populations were the first to lose services. Many drop-in centres that provided HIV testing, condoms, lubricants, peer support, and harm-reduction supplies have shut down.

Globally, the proportion of new HIV infections among key populations has continued to rise from 44 per cent in 2010 to 49 per cent in 2024.

While many countries have tried to preserve treatment programmes, data shows widening gaps. HIV testing dropped by 43 per cent in Cameroon early in 2025 and by 17 per cent in Uganda.

Viral load testing fell by up to 68 per cent in 13 surveyed countries. In Zambia, months after the funding freeze, 71 per cent of facilities still reported staff shortages, long wait times, and delays in laboratory results. South Africa experienced what observers called a “system-wide slide” in HIV service quality.

People fell out of care and returned only when disease advanced

Reduced testing and weakened community support meant that more people fell out of care and returned only when their disease was advanced, threatening to reverse years of progress in reducing AIDS-related deaths. In 2024, AIDS-related deaths stood at 630,000.

Community groups, often run by people living with HIV, deliver the majority of HIV services for key populations and vulnerable groups. Yet they remain almost entirely dependent on international support.

In 2025, more than 60 per cent of women-led HIV organisations reported losing funding or suspending operations. Youth-led groups fared no better.

“People are panicking,” says Takhmina Haidarova of the Tajikistan Network of Women Living with HIV. “If our support shuts down, women and families will have nowhere to turn.”

Even modest drops in funding could have catastrophic effects. National authorities warn that a 10–20 per cent funding cut could lead to a 135 per cent rise in new infections.

The HIV funding crisis is unfolding against a backdrop of rising repression. For the first time since UNAIDS began tracking punitive laws in 2008, the number of countries criminalising same sex relations and gender expression has increased.

People avoid clinics, stop carrying condoms, hide HIV status

In 2025, 168 countries criminalise some aspect of sex work, 152 punish possession of small amounts of drugs, 64 criminalise same sex relations, and 14 target transgender identities.

Such laws fuel fear and stigma, deterring people from accessing HIV services. Criminalisation fuels fear. People avoid clinics, stop carrying condoms, and hide their HIV status.

A study in West and Central Africa found that sex workers and women living with HIV avoid health facilities for fear of arrest. Eight in ten civil society groups operate where civic space is restricted.

Despite the turmoil, UNAIDS notes “important signs of resilience” in 2025. International donors, including European governments, have recommitted funding. The Global Fund secured US$11.34 billion in pledges for its replenishment cycle.

At the regional level, African leaders are pushing for greater health sovereignty. The African Union Roadmap to 2030 and beyond calls for diversified health financing, while the Accra Reset launched in September 2025 urges new governance and investment models.

Nigeria sharply increased its health budget, Côte d’Ivoire boosted domestic HIV spending

Some countries are taking bold steps. Nigeria sharply increased its health budget, Côte d’Ivoire boosted domestic HIV spending by up to US$85 million annually, and Tanzania introduced new excise taxes to fund HIV services. Uganda aims to double health spending, while over 30 countries are developing national sustainability roadmaps.

Uganda plans to raise domestic financing for HIV from 20 per cent to 50 per cent by 2040. Togo aims for 50 per cent by 2030, while Malawi targets 30–50 per cent by 2030.

The report says that without urgent action, the world will miss its 2030 targets. An estimated 3.3 million more people could acquire HIV between 2025 and 2030. However, the crisis also offers hope. Communities are mobilising, governments are stepping up, and new HIV prevention technologies such as long-acting injectable PrEP, now available for just US$40 a year in many developing countries, could transform prevention if countries adopt them.

“AIDS is not over,” says UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima. “But countries and communities are coming together to overcome disruption and transform the response. It is within our grasp; we must seize it.”