The Assisted Reproductive Technology Bill aims to devolve fertility services across all 47 counties and prevent exploitation, but treatment remains costly as a single IVF cycle can cost Ksh400,000 at a licensed clinic.

Elsie Wandera remembers the moment her diagnosis truly sank in. Her endometriosis had advanced quietly and aggressively until both ovaries had to be removed, and “I felt like an essence of my womanhood had been robbed” as she was never going to give birth.

“I felt like an essence of my womanhood had been robbed,” she recalls. Wandera, co-chair of the World Endometriosis Organisations and founder of the Endometriosis Foundation of Kenya, describes how “I was in a sad and depressed state,” knowing she was never going to give birth.

In many African societies, Wandera explains, a woman’s value is measured in children. “We live in a society that objectifies women…our only role seems to be to have children.”

If you can’t have children, a barrage of questions follows from relatives. From neighbours. From strangers at weddings. Yet infertility is a common reality for families in Kenya, affecting people regardless of their class, education or geography. According to the Kenya Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society (KOGS), one in three couples in Kenya struggles with it.

For decades, assisted reproduction in Kenya existed in an unregulated space; solutions were available but often unregulated, unaffordable and unsafe.

Now, after years of advocacy, Kenya is finally establishing laws to govern IVF, surrogacy, and other technologies that navigate the profound intersection of science and the desire to have a child.

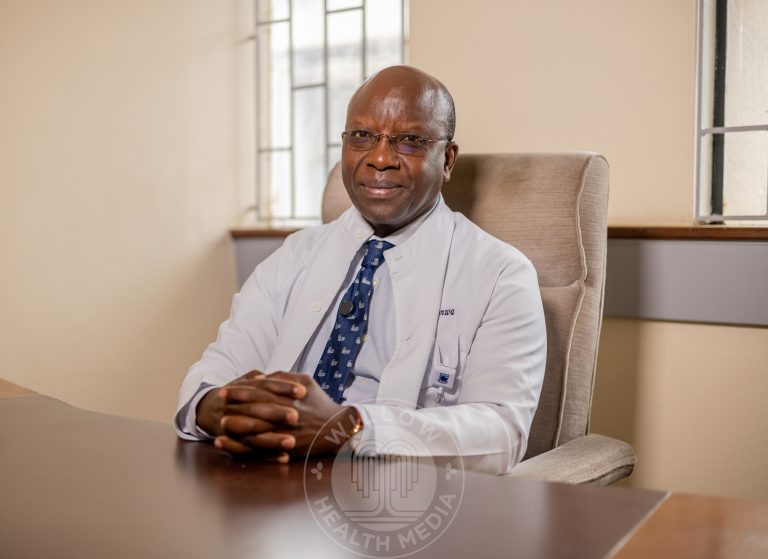

Dr Kireki Omanwa, President of KOGS, has witnessed the devastating consequences of this regulatory vacuum. “I have seen patients die because of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome,” he says bluntly.

The lack of oversight created a marketplace where desperation met profit

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, a preventable complication from fertility drugs, can cause kidney failure and death without proper medical monitoring. But without regulation, there was no guarantee that clinics followed best practices. Beyond immediate medical risks, the lack of oversight created a marketplace where desperation met profit.

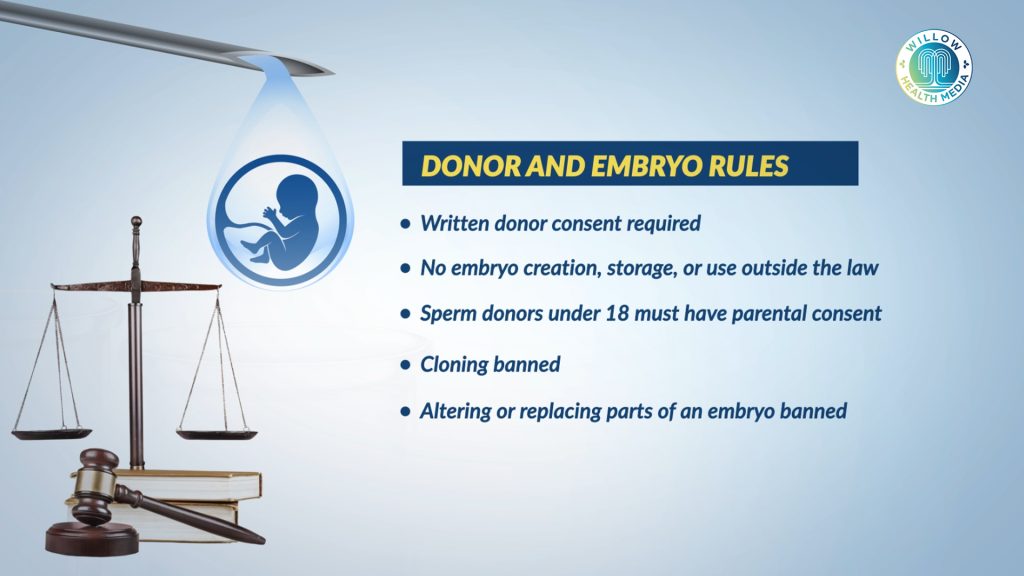

This lack of rules left critical questions unanswered: who has parental rights, what happens if intentions change, and how can exploitation be prevented?

IVF in Nairobi costs between Ksh400,000 and over Ksh1 million per attempt, with no guarantee of success. The financial burden of multiple rounds can be crushing.

Suba North MP Millie Odhiambo understands this struggle personally, having lived with fibroids and childlessness. She openly shares her story, knowing it echoes the experiences of thousands. For years, she has championed laws to regulate assisted reproductive technology, skirting resistance, skepticism, and the slow machinery of government.

The Assisted Reproductive Technology Bill, 2022, which she sponsored, is the product of years of work, expert input and complex negotiations with religious and cultural leaders. On November 11, 2025, it finally passed the National Assembly with overwhelming support.

“If technology can help people whose marriages are breaking, why not?” Odhiambo said. “We will use technology to make life easier and save marriages.”

A new Assisted Reproductive Technology Directorate will set national standards, license clinics

National Assembly Speaker Moses Wetangula welcomed the decision with personal resonance: “I know many of my relatives and friends who could benefit from this law.” The Bill now moves to the Senate before Presidential Assent. If passed, Kenya would become one of the few African nations with comprehensive assisted reproduction laws, setting a potential continental example.

At its core, the ART Bill transforms a free-for-all into a structured, state-supervised system. A new Assisted Reproductive Technology Directorate will set national standards, license clinics, and conduct yearly inspections. Only licensed clinics and qualified professionals can provide services. Violations can result in fines up to Ksh5 million or up to five years in prison, or both.

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of the Bill is how it regulates surrogacy. The law strictly bans commercial surrogacy. Surrogates can only be reimbursed for medical expenses, not paid a fee. Only altruistic, compassionate surrogacy is allowed.

Kenyan parents who are divorced, widowed, or single can use surrogacy if medically certified as unable to conceive naturally. Surrogates must be at least 25, have given birth before, and give up all parental rights at birth. Every agreement must be a written contract, witnessed by two people and can only be cancelled before embryo implantation.

Despite the law, deep-seated challenges remain. In Kenya, the narrative around infertility almost always centres on women: the questions, the blame, the stigma. But statistically, male factor infertility contributes to roughly half of all cases.

Smoking introduces thousands of chemicals which disrupt sperm production

Dr Omanwa concurs and points out that “The biggest problem with male infertility is sperm quality.” Issues like low sperm count stem from genetic conditions, infections, and lifestyle factors. “Smoking introduces thousands of chemicals, including heavy metals, which disrupt sperm production,” he explains.

For women, major causes include fibroids, severe endometriosis, and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Dr Paul Kamau Koigi, a consultant obstetrician-gynaecologist, notes that couples often try herbal remedies and spiritual solutions first and delay seeking help for 10 to 20 years and “By then, fertility potential is substantially compromised.”

The ART Bill creates a vital framework for safety and ethics, but it does not solve the problem of access. Regulation prevents exploitation, but doesn’t make treatment affordable. A licensed, ethical clinic will still charge Ksh400,000 per IVF cycle, far beyond the reach of most Kenyans. Insurance hardly covers fertility treatment, and public hospitals lack the capacity.

One promising provision is the devolution of fertility services to all 47 counties, which could expand access geographically. The Bill also mandates a confidential national database for medical tracking and donor anonymity.

Beyond enforcement lies the harder, longer work of cultural change: reducing stigma

Yet, the law cannot erase the “curse of infertility” that Wandera describes. Legal frameworks do not change cultural attitudes overnight. And critically, regulation cannot guarantee success; IVF remains a complex probability game.

If the Bill becomes law, couples will have protection and clarity for the first time. But the real test lies in implementation. Will the new Directorate be properly funded and staffed to enforce standards? Will counties invest in devolved ART services? Will penalties deter bad actors, or remain paper threats?

And beyond enforcement lies the harder, longer work of cultural change: reducing stigma, educating people about fertility, and challenging the narratives that measure a woman or a couple’s worth by their children.

The law provides a long-awaited rulebook for the womb, offering hope and recourse. But for thousands of Kenyans carrying the silent grief of childlessness, the journey from legal promise to fulfilled parenthood remains fraught with financial, medical and emotional hurdles.