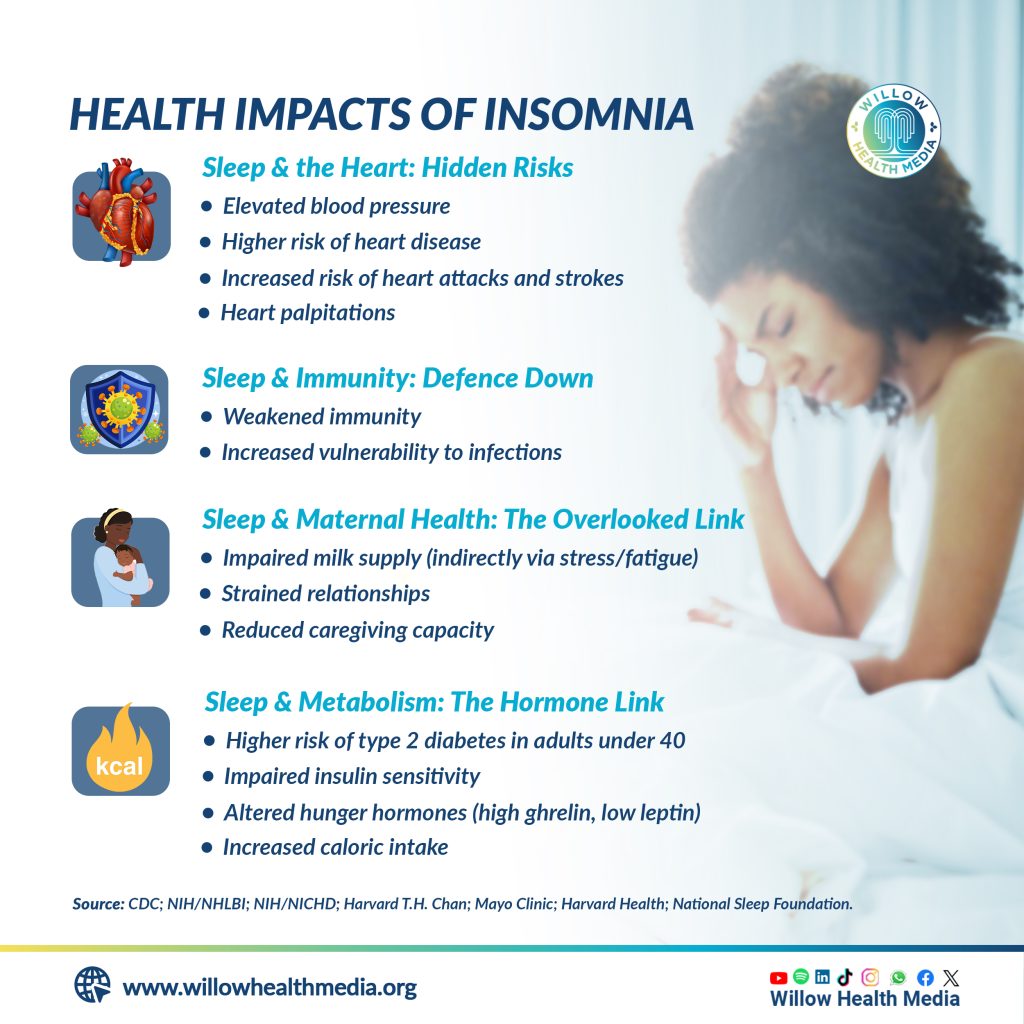

Chronic sleep deprivation elevates blood pressure, thickens arterial walls, weakens immunity and raises the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

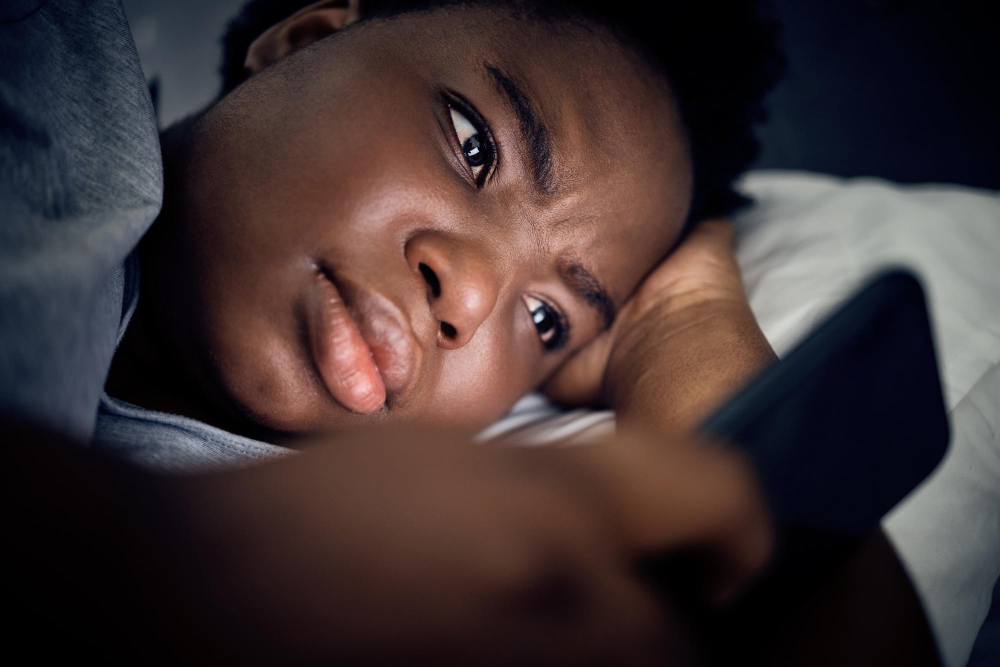

I once heard a man call Nairobi the city of light. When I asked what he meant, he said the skyline at night is dotted with thousands of tiny light bulbs. At 3 a.m., the city is still alive with the clatter of matatus and touts calling out for passengers. In Kibera, Judy, a tailor, stitches under a flickering bulb, her fingers steady but her eyes heavy with fatigue. In Parklands, Kevin, a young software developer, squints at his screen, chasing a deadline with an empty coffee mug beside him. This 24-hour hustle isn’t unique to Nairobi; it pulses across Kenya, from Nyahururu to Mombasa, stealing sleep and taking a deep toll on our health.

Take Omosh, a 37-year-old boda boda rider from Kayole. By day, he weaves through Nairobi’s chaotic traffic; by night, he guards an apartment block, sustained by three hours of sleep and endless cups of black coffee. His life mirrors countless others: students cramming for exams under dim lamps, healthcare workers pulling 36-hour shifts, hawkers counting shillings at dusk.

For many, the hustle is survival. But chronic sleep deprivation elevates blood pressure, thickens arterial walls, and raises the risk of heart attacks and strokes. At 37, Omosh is among the approximately 18 per cent of young Kenyans aged 18-29 facing hypertension, a condition that reflects Kenya’s overall hypertension prevalence of 24-29 per cent in the adult population, according to recent health surveys.

A 2019 study in Diabetes Care also links sleep loss to a 40 per cent higher risk of type 2 diabetes in adults under 40, due to impaired insulin sensitivity. Poor sleep weakens immunity, too, leaving people like Omosh vulnerable as he patrols chilly nights.

In Nairobi’s Kilimani and Parklands, Wangui, a 29-year-old virtual assistant, and Kevin, the developer, embody Kenya’s booming remote workforce. Tethered to international time zones, Wangui answers client queries at all hours, while Kevin codes for Silicon Valley startups until 5 a.m. One night, Wangui froze mid-call, her mind blank, “drowning in fog.” Kevin battles palpitations and weight gain, his body rebelling against a clock disconnected from the sun.

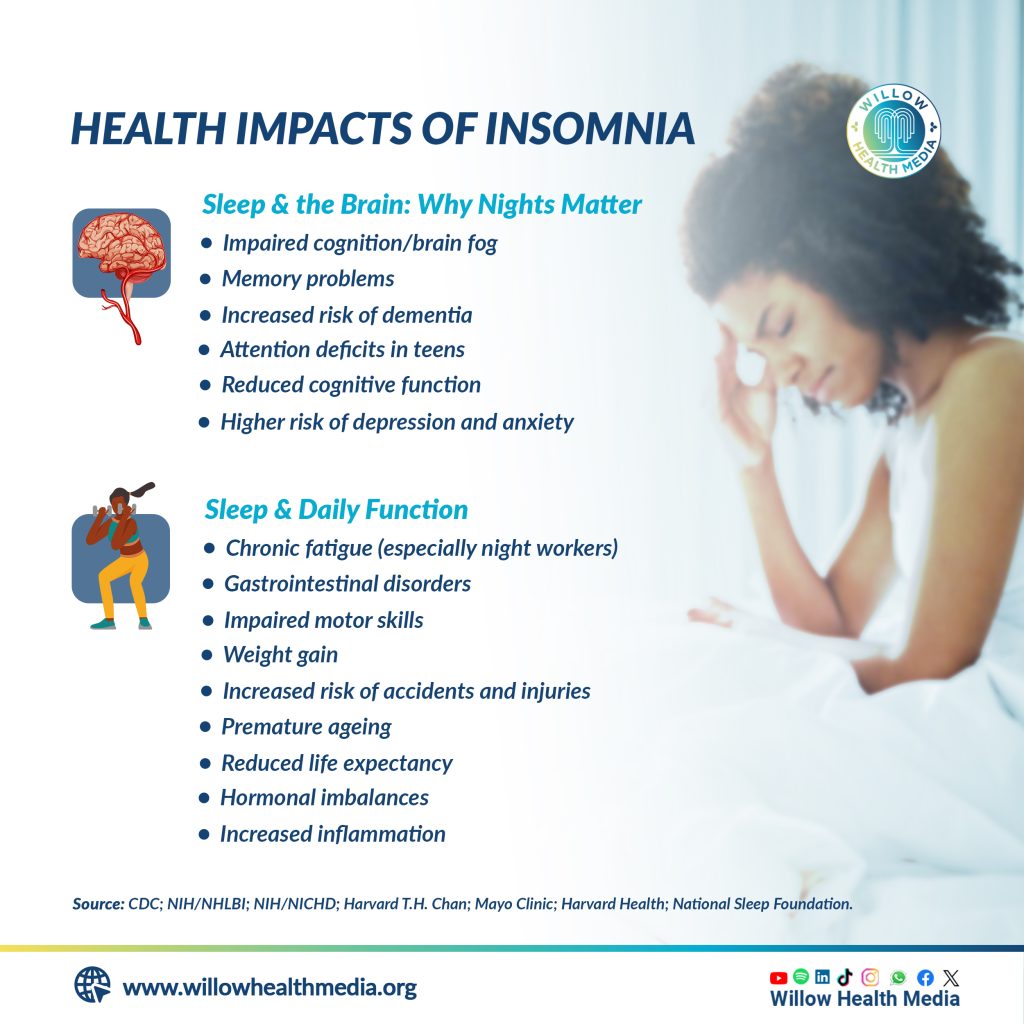

Chronic sleep loss shrinks the brain’s memory centre, increasing dementia risk

Kenya’s English proficiency and cost-effective labour market fuel this surge as local skilled workers often charge 50–70 per cent less than Western counterparts. But the “always-on” culture comes at a cost: 70 per cent of digital platform workers report irregular hours, and many moonlight in a precarious economy with 67 per cent youth unemployment, according to the Federation of Kenyan Employers. Night shifts disrupt circadian rhythms, raising the risk of metabolic syndrome by 35 per cent and heart disease by 18 per cent.

One study in Nature found that a single sleepless night impairs cognition like a 0.05 per cent blood alcohol level. Chronic sleep loss also shrinks the brain’s memory centre, the hippocampus, by up to two per cent, increasing dementia risk. For Wangui and Kevin, economic promise teeters on the edge of burnout.

This sleepless grind isn’t limited to adults. Terry, 14, wakes at 4:30 a.m. to catch a matatu to school, her eyes heavy from finishing homework past 10 p.m. Across the country, children rise before dawn, navigate long commutes, and stay up late with assignments. Studies show up to 60 per cent of secondary students get poor sleep, often linked to academic stress.

A 2016 study on university students found that stress from family, finances, and relationships reduces both sleep and cognitive function. Teens sleeping less than eight hours face a 50 per cent higher risk of obesity and a 40 per cent increase in attention deficits. Sleep is critical for brain development, especially the prefrontal cortex, which matures in young adulthood. Slipping grades and irritability aren’t laziness; they’re often signs of a brain starved for rest.

Postpartum sleep deprivation increases risk of depression, anxiety, impairs motor skills

Mothers carry a heavy load, too. A neighbour recently gave birth and confessed she never anticipated how severe the sleep deprivation would be. Her newborn wakes every hour or two, leaving her with fragmented rest, about four hours on a good night. Many new mothers report poor sleep due to night feedings.

A 2019 study found that postpartum sleep deprivation increases the risk of depression and anxiety, impairs motor skills, and hinders bonding due to reduced oxytocin. For breastfeeding mothers, it can affect milk supply. Poor sleep is also tied to strained relationships and inadequate care for the child.

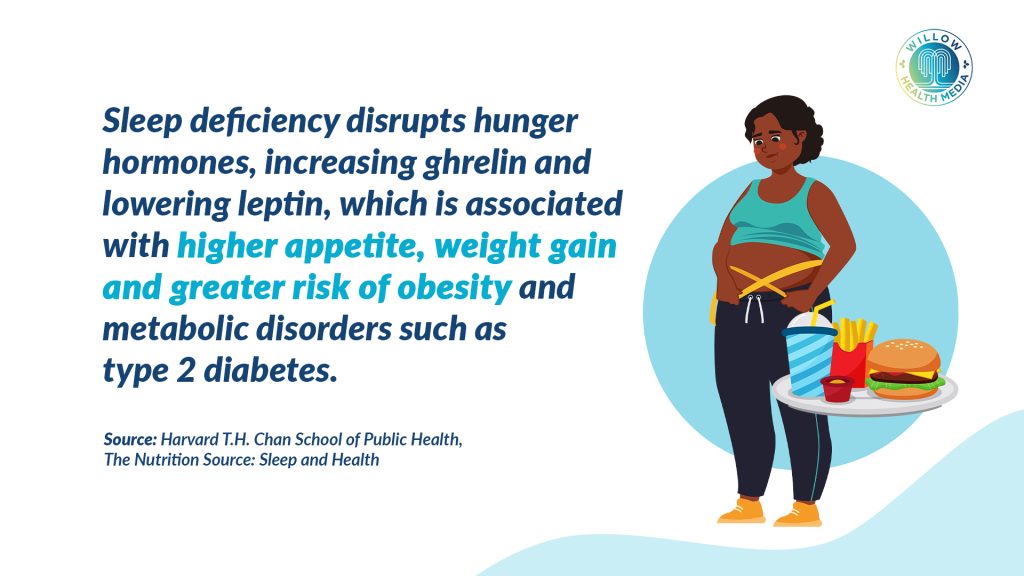

The sleepless epidemic reaches beyond cities. In Nyeri’s Mukurwe-ini, Muthoni, a 42-year-old farmer, rises at 3 a.m. to milk her cows. After a day in the fields, she weaves sisal baskets past midnight, her phone buzzing with chama (social/community group) updates, church activities, and funeral plans. Even in rural areas, smartphone penetration blurs the line between work and rest. Sleep deprivation alters hunger hormones; leptin decreases while ghrelin increases, leading to a 15 per cent rise in caloric intake and a slower metabolism. Chronic sleep loss raises body mass index by an average of 1.5 points.

But it’s not just work keeping people awake. From neon-lit urban alleys to quiet rural villages, the nightlife of drinking, partying, and drug use thrives. In informal settlements like Kibera and Mathare, young adults seek escape in cheap illicit brews, cannabis, or khat. According to NACADA’s 2022 National Survey, 4.73 million Kenyans aged 15-65 are currently using at least one substance, with young people between 15-29 identified as a particularly high-risk group.

Chewing miraa late into the night, disrupts sleep patterns, fuelling anxiety

Among university students, 26.6 per cent use alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, or synthetic drugs, often partying until dawn to numb the pressures of uncertain futures. In rural areas like Nyeri or Meru, older generations chew miraa late into the night, disrupting sleep patterns and fuelling anxiety. Urban professionals and students extend their hustle into hazy after-hours with alcohol. Some turn to over-the-counter stimulants like ephedrine or caffeine tablets to stay alert, risking heart problems and dependency.

Yet some Kenyans have no choice but to embrace the night. Security guards like Omosh, healthcare workers delivering babies, parents tending to newborns, these roles are the backbone of society, but they demand a cruel trade. A 2022 study found night workers face a 30 per cent higher risk of chronic fatigue and a 25 per cent increase in gastrointestinal disorders. Their sacrifice is noble, but the body keeps score.

Amid this crisis, solutions exist. The National Sleep Foundation recommends seven to nine hours of sleep per night to maintain cardiovascular health, metabolic balance, and mental clarity. Even a 20-minute nap can improve alertness by 30 per cent without disrupting nighttime rest. Reclaiming sleep isn’t a luxury but a necessity. For ourselves, our families, and our future.

Good sleep hygiene is essential for everyone. Here’s how to make it happen:

- Reduce blue light exposure at night: Put down the phone and step away from late-night TikTok. Cutting screen time can boost melatonin production by up to 20 per cent, helping you fall asleep faster. Since devices are designed to be addictive, therapists now recommend keeping them out of the bedroom entirely.

- Create a relaxing pre-sleep routine: Whether it’s a warm bath, reading a physical book, calming music, meditation, light stretching, or journaling, find what works for you. Consistency helps your brain link these activities with sleep, making it easier to drift off and sleep deeply.

- Optimise your sleep environment: Make your bedroom cool, dark, and quiet. Use blackout curtains, eye masks, or a white noise machine if needed. A dedicated sleep space supports better rest.

Kenya’s hustle culture celebrates hard work and resilience, but science confirms that sleep is essential. It protects your heart, sharpens your mind, and sustains your health. While the spirit of hard work shines bright, it often hides a nation on the verge of burnout. It’s time to change the story that overworking is admirable. Tonight, put away your phone, pause your hustle, and prioritise rest. By reclaiming our sleep, we restore our strength for ourselves, our families, and our future.

Dr Nyandia Maina is a Medical Doctor, Photo-Essayist and Non-Fiction Creative Writer.