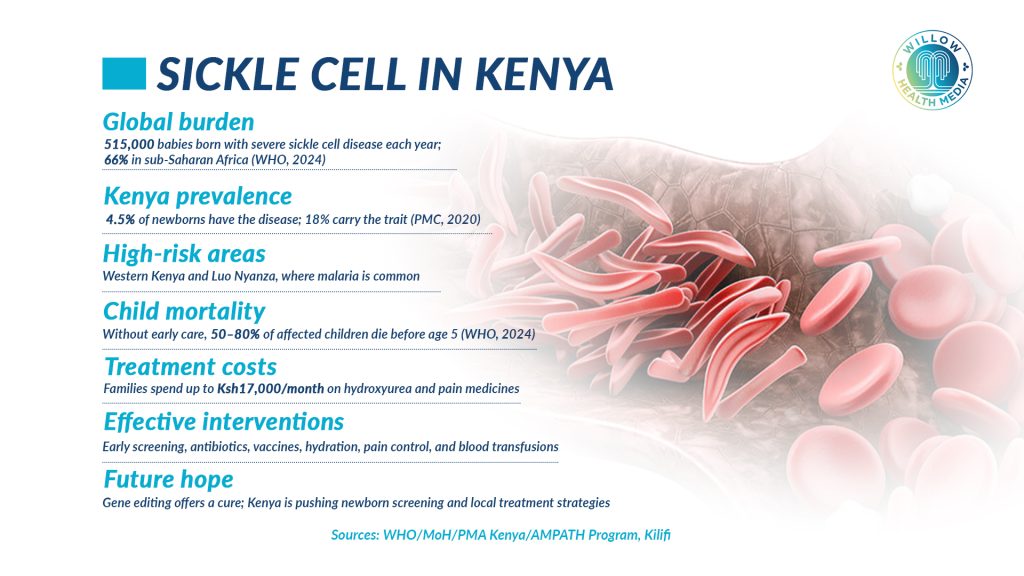

Sickle Cell Disease strikes hardest in malaria-endemic zones in Western Kenya and Luo Nyanza where one in 20 babies is born with sickle cell, while nearly one in five carries the trait.

When Selina Olwanda’s son was admitted to the hospital as a baby, she expected a routine check-up and a quick discharge. Instead, a doctor asked a single question: “What is his surname?” The answer “Ogweno” instantly raised concern as the doctor knew families from western Kenya have a high prevalence of sickle cell disease. The doctor then ordered a

Two weeks later, Selina heard the words that changed everything: “He has sickle cell.” The diagnosis, she remembers, “was delivered so casually it left me with more questions than answers.”

It became a pivotal moment that pushed Selina from a worried mother into an advocate who now leads the Children’s Sickle Cell Foundation.

Sickle cell is a genetic condition. It is not infectious. A child with the sickle gene from both parents develops it, while one who inherits only one copy becomes a carrier. Sickle cell is such that red blood cells become rigid and sickle-shaped, getting stuck in small blood vessels, triggering severe pain, infections, and organ damage.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that about 7.7 million people live with sickle cell disease globally, with three-quarters of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

Early signs are missed, yet they’re the most important, like swelling of hands and feet

For Selina, the first signs came at six months old: persistent jaundice, repeated vomiting and diarrhoea, and severe anaemia that sent them to hospital, where medics “found out he was anaemic” and, with tests confirming the diagnosis, the long road of learning started.

Dr Catherine Mutinda, a geneticist and paediatrician, explains that sickle cell symptoms start between four and six months, but early signs are often subtle and easily missed, yet they are the most important, including “Swelling of the hands and feet, frequent infections, and unexplained anaemia are usually the first warning signs.”

Why is sickle cell so common in some places, like Western Kenya and Luo Nyanza?

The short answer is evolutionary history. The sickle gene rose to relatively high frequency in many tropical regions because being a carrier (one sickle gene plus one normal gene) offered protection against severe malaria; a selective advantage in malaria-endemic regions where it was a major killer, especially around lakes and other water bodies, according to Global Health NOW. As Selina puts it, “Unfortunately, Kenya is a country that has sickle cell disease. So, everybody is a target. Get to know your status first… and once you understand your status, make informed choices.”

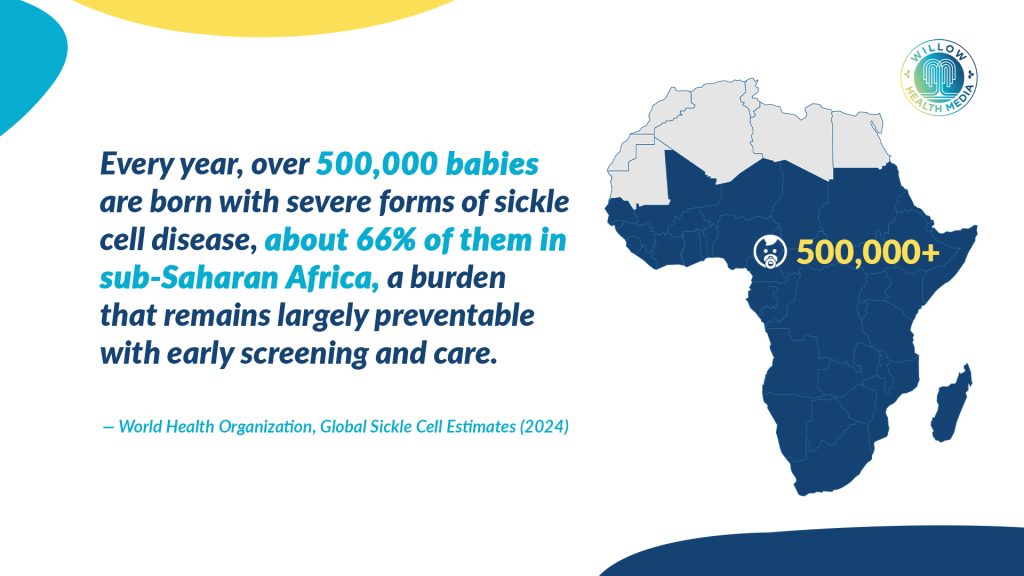

Over 500,000 babies are born with severe forms of Sickle cell annually, mostly in low and middle-income countries, with sub-Saharan Africa accounting for about 66 per cent, notes the WHO estimates for 2024.

“In western Kenya, newborn screening has shown that about 4.5 per cent of children are born with sickle cell disease and 18 per cent carry the trait, notes the High Acceptability of Newborn Screening for Sickle Cell Disease report (PMC, 2020), underlining the urgency of county-level screening programmes.”

Caregivers carry a heavy emotional toll of managing frequent hospitalisations

Selina says testing should reach young people in secondary schools and colleges, so that they understand their status before starting families and can make informed choices.

Selina’s testimony paints the day-to-day reality for families: the endless hospital visits, the unpredictability of crises, the cost of medicines, about Ksh12,000 each month for hydroxyurea, plus an additional Ksh3,000–5,000 for pain management, totalling up to Ksh17,000 monthly, out-of-pocket, without factoring in emergency blood transfusions, which can sharply increase costs.

On top of this financial burden, caregivers carry the heavy emotional toll of managing frequent hospitalisations and the uncertainty of crises. “You adjust your lifestyle to always battle between bills,” she says. “Sometimes you’re in the hospital more than you’re at work.” Many caregivers work informal jobs with no sick leave or employer support; they juggle clinic appointments, pay for medicines, and sometimes miss work because of emergencies.

Stigma makes the journey even harder. In schools, children with sickle cell may be unfairly labelled as lazy when fatigue sets in. Often, teachers are unaware that simple adjustments like giving extra fluids, allowing short rests, or planning for sudden absences can make all the difference. In the workplace, many employers still judge people by their illness rather than their abilities.

To challenge these misconceptions, Selina’s foundation brings together children with sickle cell through sports and thanksgiving events, as “Some people think sickle cell is contagious. It is not. Children should not feel left out because I have this disease.”

Detecting sickle cell at birth is crucial, as it lets doctors start preventive treatments

Dr Mutinda reiterates that “Sickle cell is not a curse. It is a genetic condition passed down from both parents. Education is key to helping families understand and manage it without blame or stigma.”

Detecting sickle cell at birth is crucial. It lets doctors start preventive treatments, like prophylactic vaccinations and regular check-ups, that protect babies from life-threatening health problems.

Kenya has started introducing newborn screening in counties like Kisumu, but Selina reckons that alone is not enough as “Screening is just a small blood test” which must be backed by accessible treatment, well-trained clinicians and genetic counselling, which is one of the things that’s lacking in this country, without which families are left with a diagnosis but no support.

Genetic counselling provides guidance after a positive test, whether it’s about planning, preparing, or seeking further diagnosis during pregnancy. Selina recalls sitting with her mother and tracing the source of the sickle cell gene to her father’s side, opening conversations about the condition, besides perspective on management and care.

Selina now advises her sons to go for testing with their partners, “When you’re ready to settle down”, to avoid going “through the same struggles again in your own family. It is about making informed decisions.”

Gene editing offers the only curative pathway we have today, but management remains very effective

There are signs of hope. Community clinics, partnerships with regional hospitals, subsidised clinic models, and targeted blood-donation drives have made a tangible difference where they exist. Like the Children’s Sickle Cell Foundation, which works with public and private hospitals to create clinic days, counselling sessions, and outreach in schools.

Others are simple, practical, proven interventions. Like prophylactic antibiotics for infants, routine vaccinations and managing pain and hydration to prevent crises and save lives.

As Dr Mutinda explains, “Gene editing offers the only curative pathway we have today, but management remains very effective. Medicines like hydroxyurea, preventive antibiotics, vaccines, and timely transfusions all significantly improve survival and quality of life.”

African researchers and policymakers are also working to improve care by expanding newborn screening and developing treatments specific to the continent.

Selina remembers meeting adults in their 30s living with sickle cell; living proof that it is survivable with the right care, and “That gave me hope,” she says. “With support, knowledge and solidarity, children with sickle cell can live full and meaningful lives.”

In a nutshell, Selina’s journey proves genetics may tell part of the story, but community, policy and simple acts of care write the rest, while Dr Mutinda’s hope is for every baby in Kenya to be screened for sickle cell at birth to “Save lives, reduce the burden on families and the health system.”