The most powerful vaccine against malnutrition isn’t manufactured in a lab—it’s stirred in a village pot, served with love and copied across homesteads…

The fight against child malnutrition in Kenya unfolds in different realities, from the vibrant, communal kitchens of rural villages to the sterile wards of urban hospitals. In Bar Agulu Village, Siaya County, mothers gather to cook nutritious meals together, embracing the Positive Deviance Hearth (PD Hearth) approach- learning from neighbours who successfully keep their children healthy with limited resources.

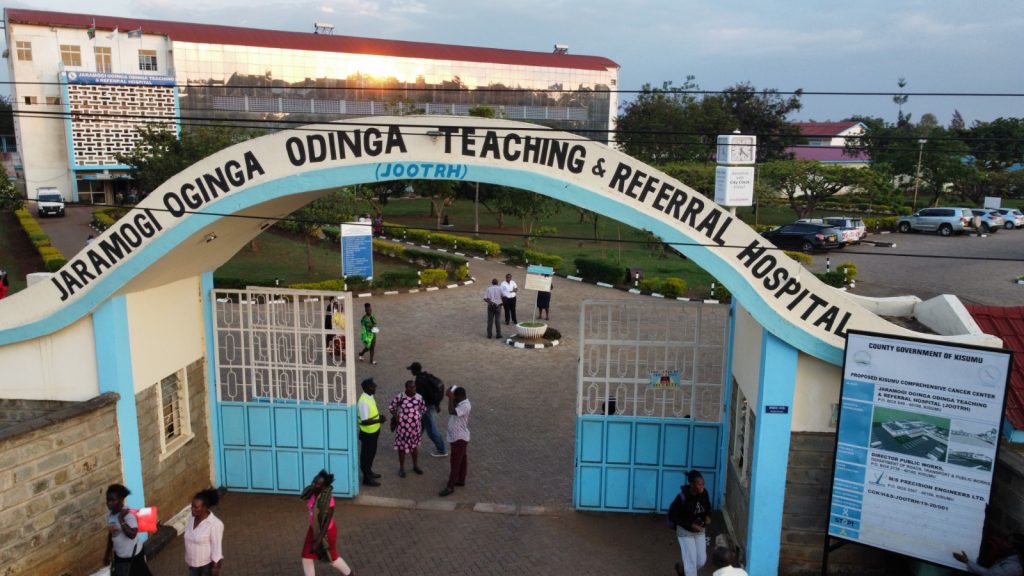

Meanwhile, at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH), doctors work around the clock to save severely malnourished children proving why prevention is crucial – treatment comes too late, too costly.

From village kitchens to hospital wards, Kenya is working to give every child a healthy start.

Take the 10 mothers in Bar Agulu village who are transforming lives via a PD Hearth session. Like Carolyn Adhiambo and Mary Akoth. They pool resources, bringing Nile perch, nutrient-rich greens, millet, cassava and bananas for a communal midday meal. The aroma of ugali wafting from the mud-thatched kitchen is proof to their collective effort, a scent bringing joy to children who, just ten days ago, struggled to eat.

In Siaya County, severe malnutrition has been a leading cause of under-five mortality

“My son barely ate before,” shares Akoth, whose child was underweight. “Now, seeing the others eat, he does too.” Such is the power of peer influence and community support, the cornerstones of the PD Hearth approach in Siaya County, where severe malnutrition has been a leading cause of under-five mortality.

Three PD Hearths are now active as part of a community-based internationally recognized model which rehabilitates malnourished children within their own homes.

“This approach aligns with the Kenya Nutrition Action Plan,” explains Dr Patrick Amoth, Director General for Health, emphasising the focus on prevention and optimal nutrition practices.

Christine Akoth, a Siaya County nutritionist, details their strategy: “We identified moderately malnourished children with the help of 15 community health assistants. We measure their weight, height, and arm circumference to track progress.”

For 12 days, the mothers attend daily sessions, learning about nutritious foods and preparing meals together. Playtime is also emphasized, with mothers crafting toys from readily available materials, fostering both physical and cognitive development. “Children eat better when they see others eating,” Akoth notes, highlighting the importance of social learning.

Treating a child with severe malnutrition costs about Ksh25,000

Carolyn Adhiambo shares her success: “My child is eating well now, gaining 200 grams in just ten days. We expect 500 grams by the end of the month.” This tangible progress fuels the mothers’ determination.

They create their own meal plans, using local ingredients like omena, fish, leafy greens, and chicken. “I used to think I was saving food by giving only one type at a time,” admits Amondi, a PD Hearth member. “Now, I understand the importance of balance. My child is active and walking, something I never thought possible.”

Contrast this with the situation at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching & Referral Hospital (JOOTRH), where six-week-old twins Sharon and Shadrack, alongside 18-month-old Ochieng, are among the many children battling life-threatening conditions.

Teenage mothers and grandmothers struggle to care for these emaciated children who’s underlying health conditions are exacerbated by malnutrition. “We receive children in shock,” says Dr Ogola Don, a paediatrician. “Malnutrition is often the root cause.”

Treating a child with severe malnutrition at JOOTRH costs about Ksh25,000 with specialised feeds like F75 and F500, essential stabilizers, adding to the financial burden. Contrast this with the community-driven PD Hearth approach.

F-75 is a therapeutic milk formula designed for the initial stabilization phase of treating severe acute malnutrition (SAM). It’s formulated to be low in protein and energy, which is essential for children who are severely malnourished and whose bodies may be unable to handle a high nutrient load immediately.

The “75” in F-75 refers to its energy content: approximately 75 kilocalories (kcal) per 100 milliliters (ml) of reconstituted formula. It’s used to help the child’s body adjust and stabilize before moving to a more nutrient-dense formula. It is used in the hospital settings for children with medical complications.

While F-100 is another therapeutic milk formula, used in the rehabilitation or recovery phase of SAM treatment. It’s higher in protein and energy than F-75, providing the necessary nutrients for the child to regain lost weight and recover. Similarly, the “100” in F-100 indicates its energy content: roughly 100 kilocalories (kcal) per 100 ml of reconstituted formula and This is also used in hospital settings.

These formulas are part of a World Health Organization (WHO) protocol for managing SAM. They are essential tools in inpatient treatment, especially for children with medical complications. It is important to understand that in recent years Ready to use therapeutic foods (RUTF) like Plumpy’Nut have become more used, especially in community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM). But that F-75 and F-100 still have a vital role in hospital-based care.

Kenya grapples with persistent challenge of stunting, wasting, underweight children

“Kenya needs about Ksh5 billion annually for nutrition,” reveals Leila Odhiambo, Assistant Director Nutrition and Dietetics. “But we often lack the resources, especially the specialized feeds.”

Kenya, like many nations, has grappled with the persistent challenge of child malnutrition. In 2021, the country faced a stark reality: 26.2% of children under five suffered from chronic malnutrition, or stunting, while 4.2% experienced acute malnutrition, known as wasting. Additionally, 11% were underweight, and four percent exhibited wasting.

However, recent data from the 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) Key Indicators Report offers a glimmer of hope, particularly in Kisumu County. Stunting rates among children under five in Kisumu have significantly decreased, dropping from 18% to 9%. Nationally, five percent of children are wasted, and three percent are overweight. The county mirrors this trend, with wasting at three percent and underweight children accounting for 3.5% of the population.

Recognising the ‘triple burden’ of malnutrition – stunting, wasting, and underweight – Kisumu County has proactively addressed the issue, especially in the face of climate change. The county adopted the Multi-Sectoral Nutrition (MSN) platforms, encouraging families to cultivate green leafy vegetables to combat malnutrition among children.

Eight million children face severe wasting, the deadliest form of undernutrition

Despite these local efforts, the global picture is heart breaking: 30 million children in 15 of the world’s most vulnerable countries are wasting away. Of these, eight million face severe malnutrition—the most dangerous form of hunger, warns the World Health Organization (WHO). Every six seconds, a child dies of malnutrition, those with severe acute malnutrition, facing an elevated risk of death from common childhood illnesses like diarrhoea, pneumonia, and malaria.

In 2020, five million children under five lost their lives—most from preventable causes. Newborns bore the cruellest burden, with 2.4 million dying before their first breath could fully fill their lungs.

Sub-Saharan Africa carries the heaviest burden. While Europe and North America see five child deaths per 1,000 births, this region suffers 74—a devastating gap that speaks to deep global inequities.

The statistics reveal a harsh truth: 45% of child deaths are linked to nutrition. Each number represents a life cut short, a potential unrealized, a family’s hope extinguished. This is not just a health crisis. It is a human crisis.

“Hospital-level intervention is costly and unsustainable,” Odhiambo emphasises. “We need a ‘business unusual’ approach, empowering households to prevent malnutrition.”

We conducted post-mortems…30% of deaths were due to malnutrition

The Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance (CHAMPS) Network data underscores the urgency. In Kisumu and Siaya, malnutrition is the leading cause of death among children under five. “We conducted post-mortems and found that 30% of deaths were due to malnutrition,” says Dr Dickens Onyango, co-director of CHAMPS Network.

Joseph Odinde, Alego Usonga Sub County Nutritionist, highlights the impact of CHAMPS data: “We decided to intervene with PD Hearths, preventing moderate malnutrition from becoming severe.”

With support from World Vision and CHAMPS, Siaya County has established three PD Hearths, equipped with MUAC tapes, weighing scales, and height boards. Community health workers are trained to identify malnutrition cases, empowering parents to take ownership of their children’s health.

The results are promising. Of the 26 children initially identified as malnourished, 22 recorded weight gain after 12 days in the PD Hearth program.

“Moderate malnutrition is silent,” Odinde warns. “Without intervention, it quickly progresses to severe malnutrition, which can be fatal.”

In Bar Agulu village, the mothers are proving that community-driven solutions, fuelled by local resources and unwavering determination, can effectively combat malnutrition. Their shared meals and collective spirit are not just nourishing bodies; they’re building a healthier future for their children and community.

The writer was a student at KEMRI Graduate School Health Journalism & Public Health Communication Course. The story is a collaboration of KEMRI Graduate School, University of Liverpool and Willow Health Media.