Roselyn Kanja Odero’s son was diagnosed with this rare neurological disorder that affects one in 100,000 children worldwide…and is sometimes mistaken for cerebral palsy.

When Roselyn Kanja Odero first held her newborn son, Morgan, there were no signs that anything was amiss. But as weeks turned to months, Roselyn began noticing the milestones were delayed. Morgan wasn’t holding his head up. He wasn’t sitting. Something wasn’t right.

“He started holding his head up around the fifth month,” Roselyn recalls. “And then started sitting at three years,” the mother of two narrates.

What followed was a long and confusing medical journey. Numerous hospital visits, recurrent infections, and no clear answers until a brain MRI changed everything. Morgan was diagnosed with Joubert syndrome, a rare neurological disorder that affects only 1 in 80,000 to 100,000 children worldwide.

Today, Morgan is eight years old and attends school, where he continues to surprise those around him. While his physical and developmental milestones trail about two years behind his peers, his emotional intelligence and cognitive spark often shine brighter than expected. His progress, though uneven, is a powerful reminder that growth doesn’t always follow the same path.

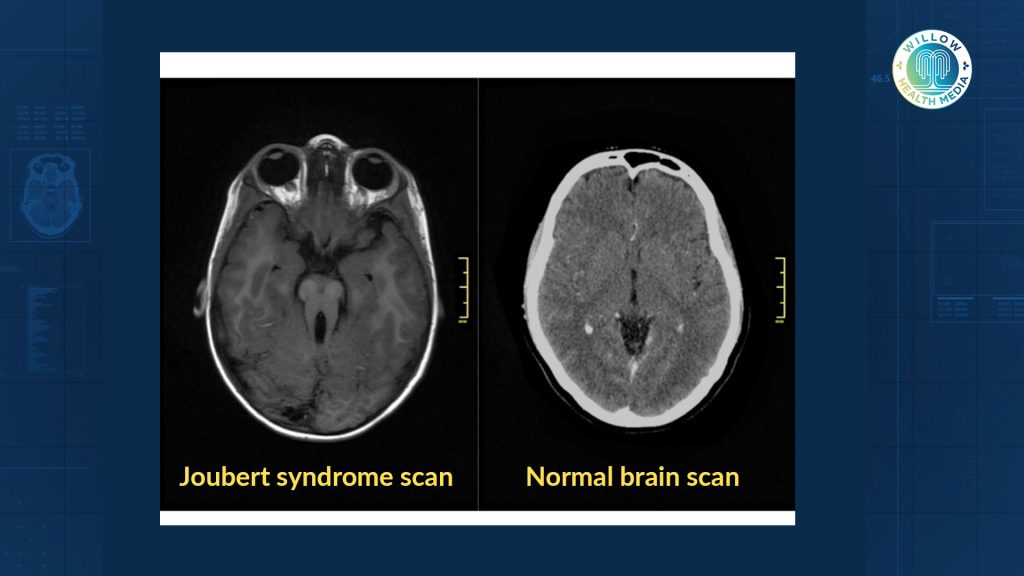

Joubert syndrome is a genetic condition caused by mutations in more than 30 known genes. It primarily affects brain development, especially the area responsible for balance and coordination. The telltale sign is a brain scan showing what doctors call the “molar tooth sign.”

“So, Joubert’s syndrome is a condition that is caused by the fact that part of the brain is not formed,” explains Dr Catherine Mutinda, a paediatrician and geneticist. The reason she says “Is because the genetic imprint or the code that is responsible for that part being formed is either not there or it’s not working.”

In the specific case of Joubert’s syndrome, the midbrain is not formed as it should be

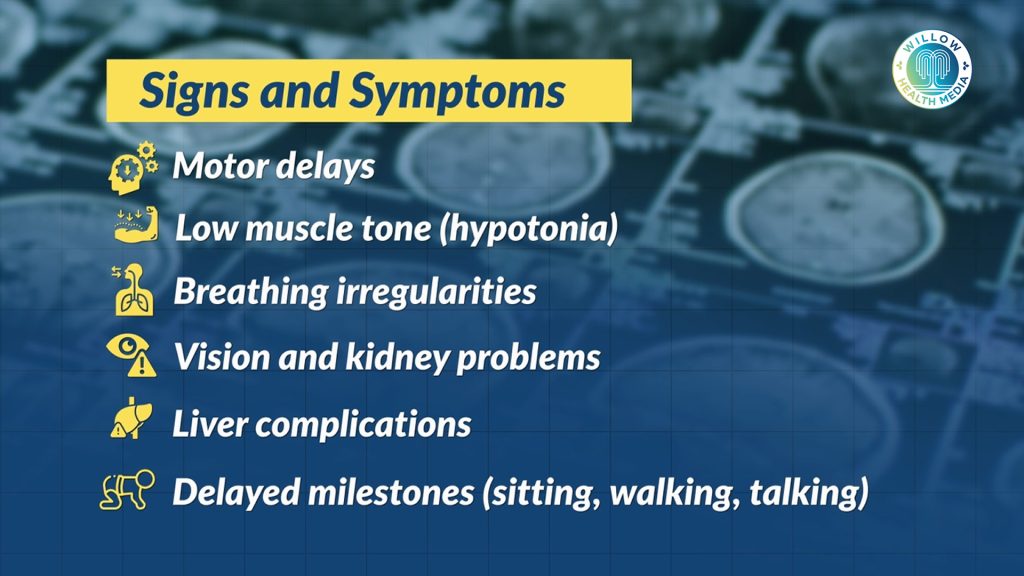

In Joubert syndrome, the midbrain, which controls vital motor functions, doesn’t form correctly. This causes a ripple effect across the body.

“The brain is a big and serious organ that controls everything,” Dr Mutinda adds. “In the specific case of Joubert’s syndrome, the midbrain is not formed as it should be. And therefore, the functions of that part of the brain are all affected. This includes balance, inability to coordinate, and the way they are moving.”

Roselyn and her husband had never heard of Joubert Syndrome before Morgan’s diagnosis. There was no known history of the condition in their families. Doctors explained that sometimes genetic conditions can occur spontaneously with no warning and no family precedent. This type of random genetic mutation is known as a de novo occurrence.

She is mindful that her older son, Morgan’s brother, could be a carrier of the same genetic mutation. She’s open about this reality and says she’s prepared to have that conversation with him when the time comes, especially as he starts thinking about starting a family of his own.

Joubert’s Syndrome has no cure, but early interventions like physical and occupational therapy can significantly improve outcomes. The financial burden of managing Morgan’s condition is immense. At one point, he required a specialised formula that cost around Ksh3,000 per pack, and he would go through one every week. Therapy remains an ongoing need, with sessions priced as high as Ksh3,000 each, and Morgan needing up to three sessions per week.

Beyond the regular classroom support, Morgan requires a dedicated special-needs teacher

He also uses a specialised stroller to support his mobility, but these aids are expensive, and Morgan outgrows them quickly. At school, his needs are even more complex: beyond the regular classroom support, he requires a dedicated special-needs teacher, since he is neither fully mobile nor verbally responsive.

Joubert Syndrome is frequently misdiagnosed as cerebral palsy (CP), especially in babies who are floppy or experience seizures. However, cerebral palsy is a broad umbrella of conditions and should always be questioned. Accurate diagnosis is essential because the treatment and prognosis differ vastly.

Dr Mutinda cautions against accepting such labels without scrutiny: “Let’s not accept CP as a blanket diagnosis. CP caused by what? That should be our question as parents.”

Dr Mutinda emphasised the critical role of parents, especially mothers, in advocating for their children’s health.

“As a mother, you are the primary caregiver, you are the primary doctor, you are the primary clinician. Trust that instinct,” she said, urging families to challenge vague or incomplete diagnoses.

Her call is clear. Parents must feel empowered to ask tough questions, push for clarity, and seek comprehensive evaluations when something doesn’t add up.

Morgan’s diagnosis was at a time when genetic counselling was still out of reach

With few local specialists and limited online information at the time of diagnosis, Roselyn’s search for answers led to a dead end.

“Google had several pages, I think ours stopped at page two. After that, it was unrelated searches,” she recalls. “You are in totally new territory.”

Roselyn received Morgan’s diagnosis at a time when genetic counselling was still out of reach for most Kenyan families, deepening the uncertainty that followed the rare diagnosis. Roselyn recalls how a sleep study prompted by Morgan’s sleep apnea, where his body would literally forget to breathe, was one of the many steps on a long, diagnostic journey.

Because the condition was so rare, she found herself carrying a file of all Morgan’s medical records, moving from one doctor to another. Often, Roselyn would have to explain his symptoms herself, helping the specialists piece together his care. The doctors who were willing to listen and learn alongside her became invaluable, helping her better understand her son’s complex condition.

Navigating life with a rare disorder meant more than doctor appointments; it was emotional labour and constant explaining.

“You hear things like, ‘Put him in the sun,’ or ‘You’re not praying enough.’ People’s opinions can sometimes be a burden.”Roselyn explains.

Even simple errands or hiring a nanny required extra planning and patience. “Support for me,” Roselyn says, “looks like having a good nanny, and a community I can talk to. Because there are so many things to navigate. Roselyn has not been spared the sting of stigma. Something as simple as a trip to the supermarket often draws silent stares, whispers, or even sneers. The sight of Morgan in his specialised stroller seems to invite judgment from strangers who don’t understand his condition.

The Kenyan government has now established a Rare Disease Working Group

Over time, Roselyn has grown thick skin, grounding herself in faith and the unwavering belief that her child is a blessing, not a burden. She’s found strength in the support of her church community and from fellow parents within Rare Disorders Kenya, the organisation she co-founded. Her advice to other parents raising children with rare conditions: “Curve out your own community”

Roselyn, together with a friend, co-founded Rare Disorders Kenya, an advocacy and support group for families navigating rare diseases.

Initially created to mark Rare Disease Day observed globally every February 28 or 29 in leap years, Rare Disorders Kenya has since evolved into a powerful platform raising awareness, providing community, and pushing for policy change.

“We wanted people to realise rare diseases are over 7,000, and the number is growing,” Roselyn says.

The advocacy is paying off. The Kenyan government has now established a Rare Disease Working Group, a significant step toward systemic change. The WHA78 Resolution on Rare Diseases, May 2025, urged countries to embed rare diseases into national health plans, ensuring early detection through strategies like newborn screening, and guaranteeing equitable access to diagnosis, treatment, and assistive technologies under universal health coverage.

One of the key issues Roselyn champions is access to genetic counselling and screening.

“It’s important to understand what it means for future pregnancies,” she says. “Even if I don’t have other children, my firstborn might be a carrier. He needs to know when he gets a partner.”Roselyn dreams of a Kenya where rare diseases are no longer hidden in silence, but understood, supported, and embraced.

“Because no family,” she says, “should have to walk this journey alone.”