‘If you are malnourished in childhood, the pancreas may not develop well, and this can cause diabetes in adulthood,’ Dr Rosslyn Ngugi, President of the Kenya Diabetes Study.

Kenya faces a mounting diabetes crisis, with a significant and growing number of adults affected. Health experts caution that the true scale is obscured by widespread under-diagnosis, suggesting the burden is far greater than current estimates indicate.

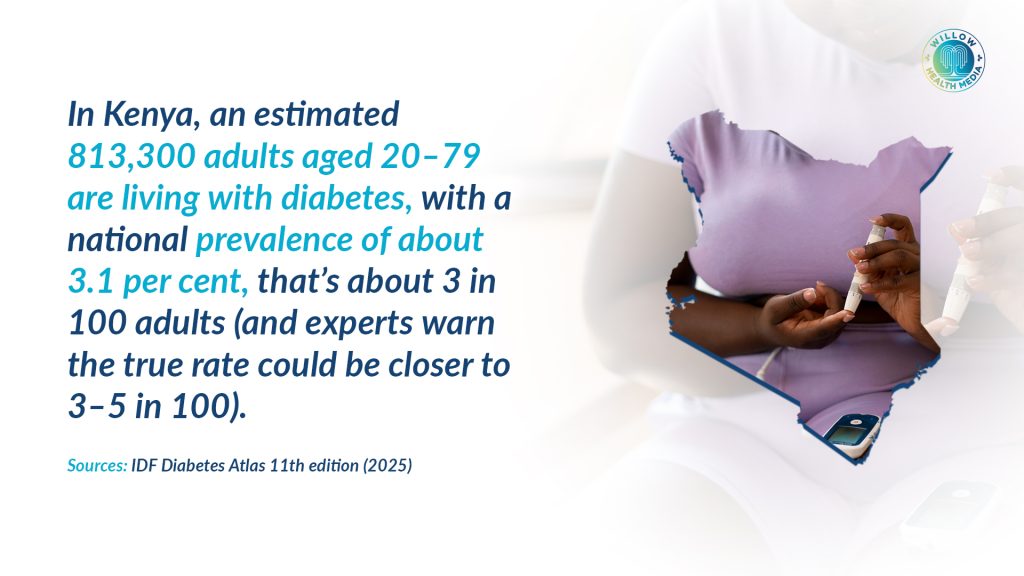

For starters, over 813,300 adults aged 20–79 in Kenya are currently living with the disease, a national prevalence of about 3.1 per cent. Experts warn the true figure is likely much higher as “The diabetes burden is about 3.3 to 4.5 per cent of the population,” says Dr Rosslyn Ngugi, President of the Kenya Diabetes Study Group (KDSG). “The problem is we think this is largely underrepresented, and we’re actually looking forward to the STEPS survey because the data we have is from 10 years ago.”

This challenge mirrors a global trend. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), an estimated 589 million adults aged 20 to 79 are living with diabetes worldwide. Even more striking, 252 million people do not know they have the disease, meaning nearly half of all adults with diabetes remain undiagnosed.

Low- and middle-income countries, including those in Africa, are carrying the weight of this rapid rise, often with fewer resources to detect, treat and manage the disease effectively.

Late detection remains one of Kenya’s biggest challenges. Many Kenyans only seek care when complications such as kidney failure, vision loss, nerve damage or cardiovascular problems have already developed. These complications are costly to treat, often lifelong, and deeply affect quality of life.

Dr Ngugi notes that “60 to 70 per cent of hospital admissions are due to diabetes-related complications. In dialysis units, 80 per cent of patients are there because of poorly managed diabetes.” This late detection not only puts lives at risk but also strains Kenya’s already stretched health system.

Rapid urbanisation, dietary changes and increasingly sedentary lifestyles are fuelling the rise. More Kenyans are consuming foods high in sugar, salt and unhealthy fats, while physical activity has decreased dramatically.

Dr Caroline Mithi, a physician and endocrinologist at KUTRRH, points to behavioural factors as major drivers. “The main factors driving diabetes are sedentary lifestyle, excessive smoking, alcohol intake, lack of exercise, and high-carbohydrate, high-fat diets,” she says.

Type 2 diabetes, once considered a condition of older adults, is now affecting younger Kenyans. “We’re seeing type 2 diabetes earlier, even from age 30. The recommendation now is that from 30 years old, everyone should have an initial diabetes screen and then annually after that,” Dr Mithi explains.

Children and adolescents are also increasingly affected. According to a report by the Access to Medicine Foundation 2025, Kenya ranks 44th among 113 low- and middle-income countries in the prevalence of type 1 diabetes among children and young people under 20, with cases rising annually. Some children come to the hospital late, already showing signs of severe complications.

Dr Mithi says type 1 cases must be managed urgently and consistently: “Type 1 diabetes happens because patients have no insulin, and they need lifelong insulin therapy. Treatment is expensive, and many families struggle with affordability, access and proper storage of insulin.”

Kenya is also seeing a wider range of diabetes types than ever before. Dr Ngugi highlights a form linked to childhood nutrition: “We are finding malnutrition-related diabetes.” If you are malnourished in childhood, the pancreas may not develop well, and this can cause diabetes in adulthood.”

Meanwhile, lifestyle-related type 2 diabetes remains the most common, accounting for about 80 per cent of all cases. Newer forms, such as “thin” diabetes and LADA (Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults), are also being diagnosed more frequently.

Pregnant women are at particularly high risk. Gestational diabetes now affects one in six pregnancies globally, and Kenya is no exception. Dr Ngugi notes a rise in cases among older pregnant women and those with risk factors such as obesity.

As part of a recent global health observance, the World Health Organisation (WHO) released its first-ever global guidelines for diabetes in pregnancy. The new standards aim to improve care for the 21 million women affected annually.

WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus emphasised the importance of the new guidance: “These guidelines are grounded in the realities of women’s lives and provide clear, evidence-based strategies to deliver high-quality care for every woman, everywhere.”

The guidelines outline 27 key recommendations, including individualised nutrition and activity plans, regular blood glucose monitoring, targeted medication for type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes, and multidisciplinary support for high-risk women. Kenya’s health facilities are expected to gradually integrate these recommendations into antenatal care.

Diabetes is often called a silent disease because many symptoms are subtle or mistaken for stress or fatigue. Frequent urination, excessive thirst, unexplained weight loss, fatigue and blurred vision are common early signs, but often ignored.

Dr Mithi warns, “By the time you’re getting complications and presenting to the hospital, it’s pretty late. Early screening is our biggest call today.”

Dr Ngugi adds, “You won’t know what’s killing you unless you get tested… my challenge to you is: get tested, and don’t go alone, take a friend or a family member.”

Both experts emphasise prevention as Kenya’s most powerful tool.

Dr Ngugi points to growing community initiatives. “Community health promoters are now screening people in homes using glucometers. If the reading is high, low or normal, they refer appropriately. People are taking screening more seriously.”

Workplaces also play a crucial role. Dr Mithi calls for greater support for people living with diabetes. “Provide safe spaces for people to test their sugars and inject insulin. Allow time for medical visits. Offer healthier meal options. These small changes make workplaces more inclusive.”

She adds that addressing obesity, a major risk factor, must become a national priority. “Obesity is a disease and one of the main drivers of diabetes. Let’s stop the stigma and provide proper treatment, from nutrition therapy to medical therapy.”

Kenyans are urged to get screened, especially adults over 30, adopt healthier diets, increase daily physical activity, attend regular medical check-ups, support family members living with diabetes, and push for access to affordable insulin and essential medications.

Diabetes is not just a medical issue- it is an economic, social and national development challenge. But with early detection, preventive action and strong health systems, Kenya can reverse the trend.

As Dr Ngugi puts it, “Prevention is better than cure. Catch it early, prevent complications, and reduce the economic burden. Everyone is at risk, including me.”

Graphics by Arthur Mbuguah.