Over one million Kenyans have been treated for H. pylori this year alone, but most diagnoses are wrong due to faulty blood tests costing between Ksh1,600 and Ksh4,500 for unnecessary treatment kits.

In busy Nairobi, Brian Wekesa knows the familiar pain that follows a meal from street food stands. “I begin by feeling bloated, then abdominal pain, especially after eating food with acidity like beans, green grams, and sometimes even taking tea,” he says, remembering one painful episode after tea and chips masala. “I suspect the milk was bad because how could tea get me food poisoning?”

This recurring nightmare led Brian through multiple diagnoses for H. pylori – a stubborn, spiral-shaped bacteria that attacks the stomach. Each time, blood tests at different facilities showed positive results. Each time, he bought treatment kits for between Ksh1,600 and Ksh4,500. Two weeks of medicine would clear symptoms, but they returned when he resumed eating his beloved street food.

Brian struggled with the prescribed drugs. “I took the treatment for a week and stopped,” he admits. “First, the kit would make me feel worse because of the side effects of the combination of drugs, and one time I did not even finish the dose because, you know, how hard it is, especially when you have to go to work, so I stopped halfway.”

His frustration peaked after three positive blood test diagnoses. Finally, a doctor suggested a stool The results turned negative for H. pylori. Instead, Brian had hyperacidity in his stomach, for which he was treated. His problems were resolved.

University student Hellen Musyoka faced similar confusion in 2019. Sharp stomach pains, gas, and loose stools disrupted her studies in her fourth year. “I would have a painful, bloated abdomen and gassy stool. I would always be dehydrated, so I drank lots of fluids to soften my stool and ease the gas,” she recalls.

More tests led to an H. pylori diagnosis and instructions to buy a treatment kit

Her first hospital visit led to a Flagyl prescription without any tests. After another episode, doctors performed a stool test and found a bacterial infection. When her condition worsened, more tests led to an H. pylori diagnosis and instructions to buy a treatment kit.

“I did not buy it because it cost Ksh4,500. I was still struggling with finances in school. So, I was given Omeprazole and an antacid and was asked to avoid acidic foods,” she explains.

These stories represent thousands of Kenyans caught in what medical experts now call a “perceived scam”-over one million Kenyans treated for H. pylori this year alone, according to the Government’s Disease Registry, which lists Nairobi, Nakuru and Meru as the worst hit. Lamu and Tana River have the fewest cases.

Most diagnoses are wrong due to faulty blood tests that cannot differentiate between active and past infections.

Dr Riro Mwita, a physician at Kiambu Level 5 Hospital, doesn’t mince words: “It’s a genuine problem, but people have taken advantage of that to get money”, as the core issue lies in misinterpreting blood tests for H. pylori antibodies.

“The scam is where they are told they have the antibodies without being explained to them, and they are put on treatment, and the treatment is very expensive. So, the person will always go to the hospital, and the antibodies are positive because they don’t disappear; they buy the medicine,” Dr Mwita explains.

Most private clinics want you to buy the kit, so they test the blood, which is wrong

Brian’s case perfectly illustrates this pattern: three blood test diagnoses, expensive treatments, recurring symptoms, until a stool test revealed the truth.

Dr Rita Muthami, Chief Pharmacist at Kiambu Level 5 Hospital, explains that “most private clinics would want you to buy the kit, so they test the blood, which is wrong, because anybody can have an antibody but not the bacteria itself.”

Her advice is crystal clear: “Do not begin taking treatment for H. pylori if you did not take a stool test, because that blood test may come back positive for H. pylori, yet it is only the antibodies from a previous infection being detected.”

Dr Winnie Mutai, a microbiologist, argues that blood tests create confusion as they “may show H. pylori from a previous infection because this person has already been treated, but you will still see the presence of those antibodies.” These antibodies can linger long after bacteria have been cleared, making results meaningless for current infections.

In contrast, stool antigen tests directly detect H. pylori proteins in faeces, definitively confirming active infections. The World Health Organization (WHO) clearly states that blood antibody tests are less accurate, showing only previous infections rather than active ones.

Dr Mutai identifies four diagnostic methods: blood tests, stool antigen tests, endoscopy, and breath tests. However, stool antigen tests and endoscopy are the most reliable. The breath test measures carbon dioxide levels in exhaled air because H. pylori produces the urease enzyme that creates carbon dioxide when breaking down stomach acid.

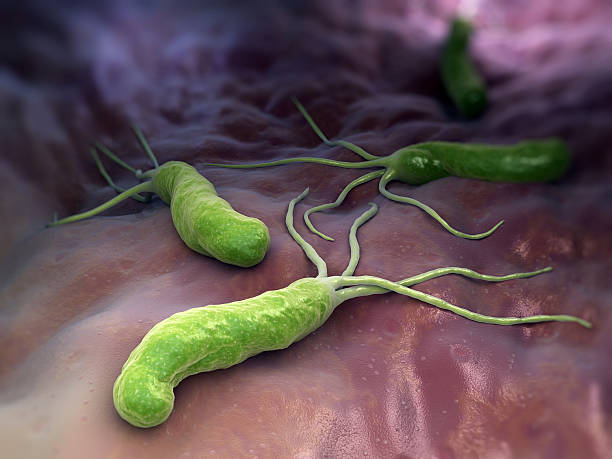

H. pylori bacteria are perfectly adapted to survive the stomach’s harsh acid environment

H. pylori, or Helicobacter pylori, is a spiral-shaped bacterium perfectly adapted to survive the stomach’s harsh acid environment. It produces the urease enzyme to neutralise acid and toxins that kill stomach lining cells, causing painful peptic ulcers.

Common symptoms include nausea, heartburn, stomach pain, and in severe cases, black stool or vomiting blood. Dr Mwita warns that without proper diagnosis, some patients might be misdiagnosed with stomach cancer, which can present similarly.

Seven in every ten Africans carry H. pylori, making it extremely common in Kenya’s crowded communities where poor sanitation creates ideal breeding grounds. The bacteria spread through contaminated food and water, poor hygiene, and person-to-person contact, especially affecting children under 10 who have weaker immune systems.

“All these factors contribute to person-to-person transmission, and the bacteria can also be transmitted through contaminated food and water,” Dr Mutai explains. H. pylori is often caught in childhood, particularly by children under 10, through shared food, utensils, or saliva from mothers and caregivers.

High costs force many patients like Hellen to seek cheaper alternatives or skip treatment entirely. When students and low-income earners cannot afford proper testing, they become vulnerable to blood test-based misdiagnoses.

Misuse of antibiotics based on incorrect blood test results leads to antimicrobial resistance

Dr Muthami notes that some institutions now insist on stool antigen tests before prescribing treatment, but many private clinics continue pushing expensive kits based on unreliable blood tests.

When H. pylori is genuinely present, medical professionals typically prescribe what’s called “triple therapy” according to established treatment guidelines. Dr Muthami explains that this standard approach involves a combination of medications that must be taken exactly as prescribed by qualified doctors for the recommended duration.

If initial treatment doesn’t work, medical professionals may adjust the treatment plan using different medication combinations. For severe cases with painful ulcers, doctors may provide initial relief before starting the main treatment course, she notes.

However, misuse of antibiotics based on incorrect blood test results contributes to antimicrobial resistance. “This occurs when the bacteria no longer respond to standard treatments like metronidazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin due to mutations in the genes coding for resistance, or when the bacteria form a biofilm, which makes it harder for antibiotics to penetrate,” Dr Mutai explains.

She adds that treatment failure often occurs when patients stop medication once symptoms improve, “leading to recurrent infections.”

She advocates for “susceptibility-guided therapy”, where doctors test H. pylori against antibiotics first, like matching keys to locks- before prescribing. This “test-before-treat” approach could stop failed treatments.

Similar scams include cancer misdiagnoses leading to unnecessary chemotherapy

Dr Mutai further explains that growing H. pylori in labs for antibiotic testing is difficult, so doctors often prescribe without knowing if treatments will work. This explains why many patients don’t improve after treatment.

The H. pylori issue fits into Kenya’s broader pattern of medical scams exploiting patient anxiety and lack of medical knowledge. Similar scams include cancer misdiagnoses leading to unnecessary chemotherapy, overpriced “detox products” with no scientific backing, and unproven arthritis cures.

Recently, the government shut down 31 hospitals over fraudulent SHA claims, highlighting widespread healthcare fraud.

Dr Mwita has seen cases where people under H. pylori treatment, when sent for antigen tests, receive negative results, leading him to discontinue treatment immediately.

Medical experts unanimously recommend demanding proper stool or breath tests before any H. pylori treatment. “For medics, get it right. Are you interested in a previous infection or a current infection? Know why you are requesting a blood test, because a blood test will only show a previous infection, and this will lead you to prescribing treatment for something which is not there,” Dr Mutai urges.

The solution lies in empowering Kenyans to demand accurate testing, avoiding the cycle of misdiagnosis and unnecessary expenses that have cost the country millions in wasted treatments, considering no H. pylori vaccine exists.