Kenya’s top hospitals are a paradox: cutting-edge surgeries and world-class doctors navigating crumbling corridors, broken machines, endless patient queues… a mixture of medical brilliance dimmed by underfunding, thin staffing, worn-out equipment, and wards bursting at the seams.

In the heart of Kenya’s medical landscape stand the national referral hospitals—beacons of hope where miracles unfold daily. They are not just hospitals but centres of excellence, where life-saving transplants, cutting-edge cancer care, and advanced neurological treatments become a reality.

They are also classrooms without walls, training the next generation of doctors and nurses through university partnerships. They are labs of innovation, driving research and technology—from clinical trials to medical breakthroughs—while guiding national health campaigns, educating communities, and influencing policy.

Indeed, these hospitals are the backbone of a stronger, healthier Kenya. Yet to keep this lifeline beating, they need more … more skilled staff, better funding, modern infrastructure, and smarter systems.

A system under strain

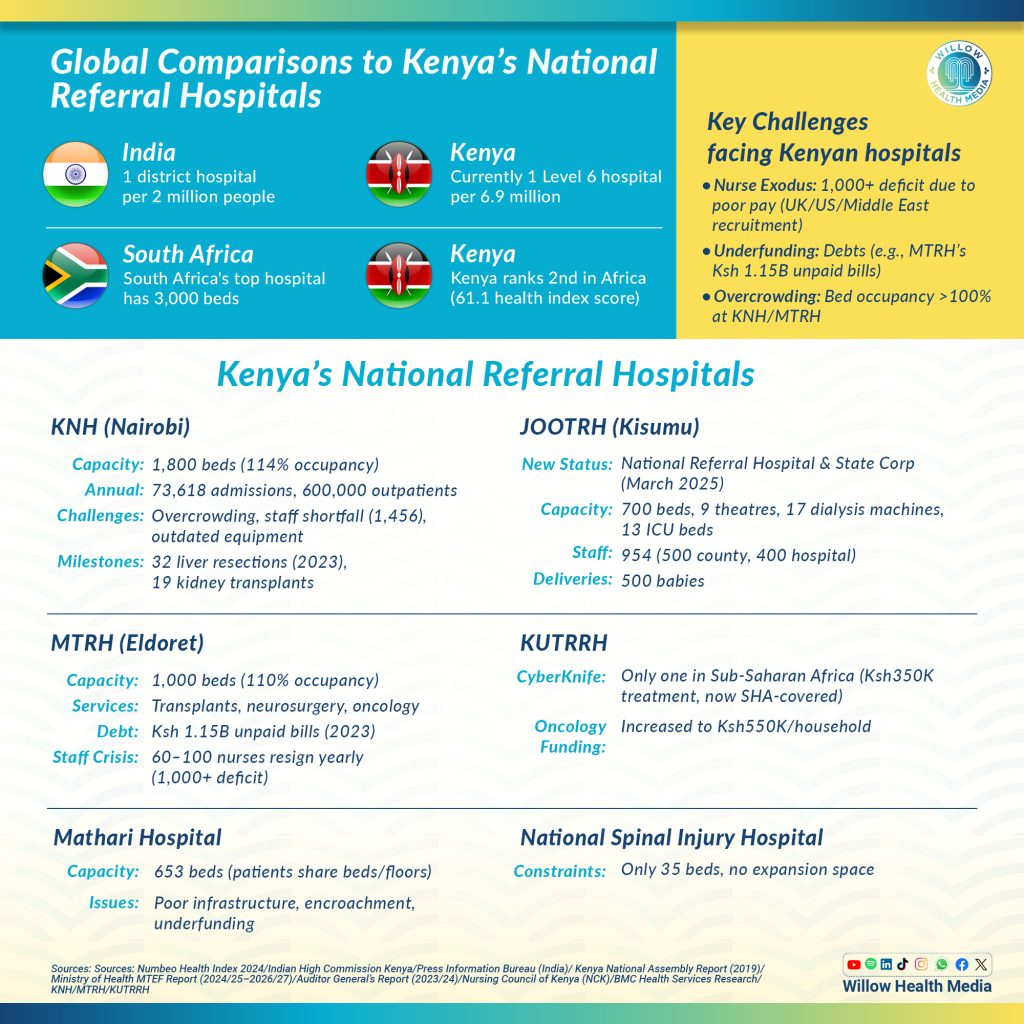

This is their story—and Kenya’s future. Take Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH), which in March became Kenya’s sixth national referral facility, joining Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH), Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH), Mathari National Teaching and Referral Hospital (MNTH), National Spinal Injury Hospital (NSIH), and Kenyatta University Teaching, Referral and Research Hospital (KUTRRH).

Originally commissioned in 1969 by founding President Jomo Kenyatta, JOOTRH—where 500 babies are delivered monthly—is now a teaching hospital for Maseno and Uzima Universities.

Its CEO, Dr Richard Lesiyampe, says like other national hospitals, JOOTRH faces severe staffing shortages. The 700-bed hospital has 954 staff against a required 2,500. Of these, 500 are employed by Kisumu County and 400 by the hospital itself. Many are on temporary contracts with meagre pay.

“We need a staff of 2,500—700 of them nurses and the rest consultants and technical staff,” says Dr Lesiyampe. He recalls meeting a worker who had served 24 years earning Sh14,000, alongside others with nine, 12, 16, even 25 years of service—all on temporary contracts. One diploma nurse has earned Sh20,000 for seven years, and a medical officer with a degree earns Sh90,000 gross—or just Sh60,000 after deductions—while working beside peers earning three times as much.

“We have suffered with the few nurses and consultants we have,” he laments, citing Othaya Hospital, which has 300 beds and 1,400 employees.

A 2019 report by Parliament’s Health Committee, chaired by MP Sabina Chege, revealed Kenya’s national referral hospitals were in crisis. Six years later, there is no updated assessment of their condition.

Overwhelmed and underfunded

Consider Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) in Eldoret. Serving more than 25 million people across 21 counties, MTRH runs at 110% capacity with 1,000 beds, treating 1,500 outpatients and 1,200 inpatients daily. It provides specialised services such as transplants, open-heart surgeries, and cancer care, primarily for eight key counties including Uasin Gishu, Kakamega, Baringo, Trans-Nzoia, Homa Bay, Bungoma, Nandi and Kericho.

But MTRH is also facing a financial crisis. According to the Auditor General’s Report (June 2023), the hospital has accrued unpaid bills of Ksh1.15 billion since 2001. Uncollected fees from individuals jumped from Sh408.2 million in 2021/22 to Sh1.15 billion in 2022/23.

Meanwhile, nurses are leaving in droves. CEO Dr Philip Kirwa says: “At least 60–100 skilled, long-serving nurses resign annually for better-paying jobs abroad,” leaving the hospital with a deficit of over 1,000 nurses. “I’m worried the situation is getting out of hand. Many of our 4,500 nurses are preparing to relocate to the Middle East and Europe.” Filling the gap has been difficult due to budget constraints from the National Treasury.

The Nursing Council estimates that Kenya loses about 800 nurses annually. This worsens patient-to-nurse ratios and leads to burnout. According to a BMC Health Services Research study, training one nurse costs Ksh5.59 million, with lifetime productivity losses of Ksh43.89 million per emigrating nurse over 32 years. Worse still, there’s no national reintegration plan for returning health workers.

Kenyatta and Mathari: Giants in trouble

Does Kenyatta National Hospital—Kenya’s largest facility—fare any better? Not really.

With 1,800 beds, 50 wards, and 28 theatres, KNH operates at 114% capacity, handling over 2,000 inpatients and 2,500 outpatients daily. That translates to 73,618 admissions and 600,000 outpatient visits annually.

Despite this, the hospital faces underfunding, outdated equipment, and a staffing shortfall of 1,456. Still, it has made progress: surgeries rose from 30,451 in 2020/21 to 37,307 in 2022/23, including complex neurosurgery, cardiothoracic and orthopaedic procedures. In 2022/23, KNH performed 19 kidney transplants (up from 15) and 32 major liver resections.

A 2017 Kenya-India agreement to build East Africa’s largest cancer hospital remains stalled. However, India did donate a Ksh125 million Bhabhatron II cancer therapy machine, significantly boosting treatment capacity.

Meanwhile, Mathari National Teaching and Referral Hospital struggles. With 653 beds, patients often share beds or sleep on floors due to dilapidated infrastructure. A Ksh12.5 million renovation was allocated, but the hospital still suffers from poor management and lacks autonomy.

The National Spinal Injury Hospital, the only spinal rehab centre in the region, operates with just 35 beds and faces severe challenges, including limited space, staff shortages, and outdated equipment.

Glimmers of Innovation: KUTRRH’s Cyberknife

Not all is bleak. Kenyatta University Teaching, Referral and Research Hospital (KUTRRH) has made significant strides. In 2022, it became the first Sub-Saharan African facility—and second after Egypt—to offer CyberKnife radiotherapy.

The CyberKnife system uses a robotic arm to treat tumours with pinpoint precision, including in delicate areas like the brain and spine. It requires no incisions, adapts to patient movements, and protects healthy tissue. Most patients complete treatment in one to five sessions with minimal side effects.

The Ksh675 million system can treat 20 patients a day, each session costing about Ksh350,000—now fully covered by the Social Health Authority (SHA). Since March 2025, oncology coverage has risen to Ksh550,000 per household, improving access. KUTRRH also partners with Kenyatta University on cancer research and trials, driving local innovation.

Solutions within reach

Solutions are not out of reach. Titus Mumia, Health Systems Manager and former administrator at Kakamega County Teaching and Referral Hospital, says national hospitals need not only motivated but also specialised professionals, alongside general practitioners, nurses, midwives, anaesthetists, and critical care staff, supported by lab technologists and radiographers.

Mumia notes that national hospitals are overwhelmed partly due to systemic failures in lower-level facilities, which often refer even minor cases like malaria due to a lack of drugs and equipment. This floods referral hospitals with unnecessary cases, causing congestion and long waits.

He advocates for better staffing, remuneration, and professional development, as well as stronger primary healthcare, increased budgets, better insurance coverage, and private-sector partnerships.

Dr Scarlet Muhadia, a dental surgeon and healthcare management expert at Strathmore University, adds that the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (KEMSA) needs strengthening. She pushes for digitisation through Electronic Health Records (EHR), telemedicine, and AI-driven diagnostics to boost efficiency and outcomes. “Stockouts and procurement inefficiencies hamper delivery,” she says. “We need better supply chains, emergency facilities, and equipment maintenance.”

Growing the network

According to Dr Issah Kweyu, six national referral hospitals aren’t enough for 55 million people. He notes that globally, the benchmark is one referral hospital for every 5–10 million people. “Kenya ideally needs three to five more facilities in underserved areas like North Eastern, Coast, and South Rift.”

To compete globally and reduce outbound medical tourism, Dr Kweyu calls for improved specialised care, particularly in oncology, cardiology, and neurosurgery, along with better infrastructure and faster scheduling via telemedicine. He supports promoting local medical tourism, expanding training, and offering subsidies to build confidence in the system.

A regional comparison

India, serving 1.4 billion people, has 714 district hospitals (1 per 2 million), 1,340 sub-divisional hospitals, and 362 medical colleges. Kenya, with 55 million people, has just eight Level 6 hospitals—roughly one per 6.9 million. Matching India’s ratio would require 27 referral hospitals.

South Africa boasts the continent’s largest hospital, Chris Hani Baragwanath, with over 3,000 beds. Kenya ranked second in Africa in the 2024 Numbeo Health Index (score: 61.1), behind South Africa (64). Globally, Kenya placed 51st—a sign of progress, but also of how much further we must go.

The numbers are clear: Kenya’s health infrastructure trails comparable countries in both access and capacity. But the potential to rise, expand, and lead is already beating at the heart of its hospitals.