Rwanda ensured most of its 13.3 million people could access a health facility within 30 minutes

So, here’s something pretty impressive about Rwanda—they’ve made significant strides in reducing reliance on donor aid and developing ways to fund their own health system.It is all thanks to strong leadership, smart policies, and some thoughtful health financing strategies. In fact, they’ve become such a standout example other African countries, like Kenya, would borrow some inspiration as was evident during the Africa Health Agenda International Conference (AHAIC) in March 2025.

Rwanda is really showing how it’s done: Prioritizing domestic resource mobilization, innovative financing mechanisms and a people-centred approach to Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

According to Dr Theopista Kabuteni, a Technical Officer at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Rwanda, leadership played a pivotal role as the “government showed that with strong leadership and commitment, achieving universal health coverage was possible. Policies did not just exist on paper they were executed with precision,” she emphasized.

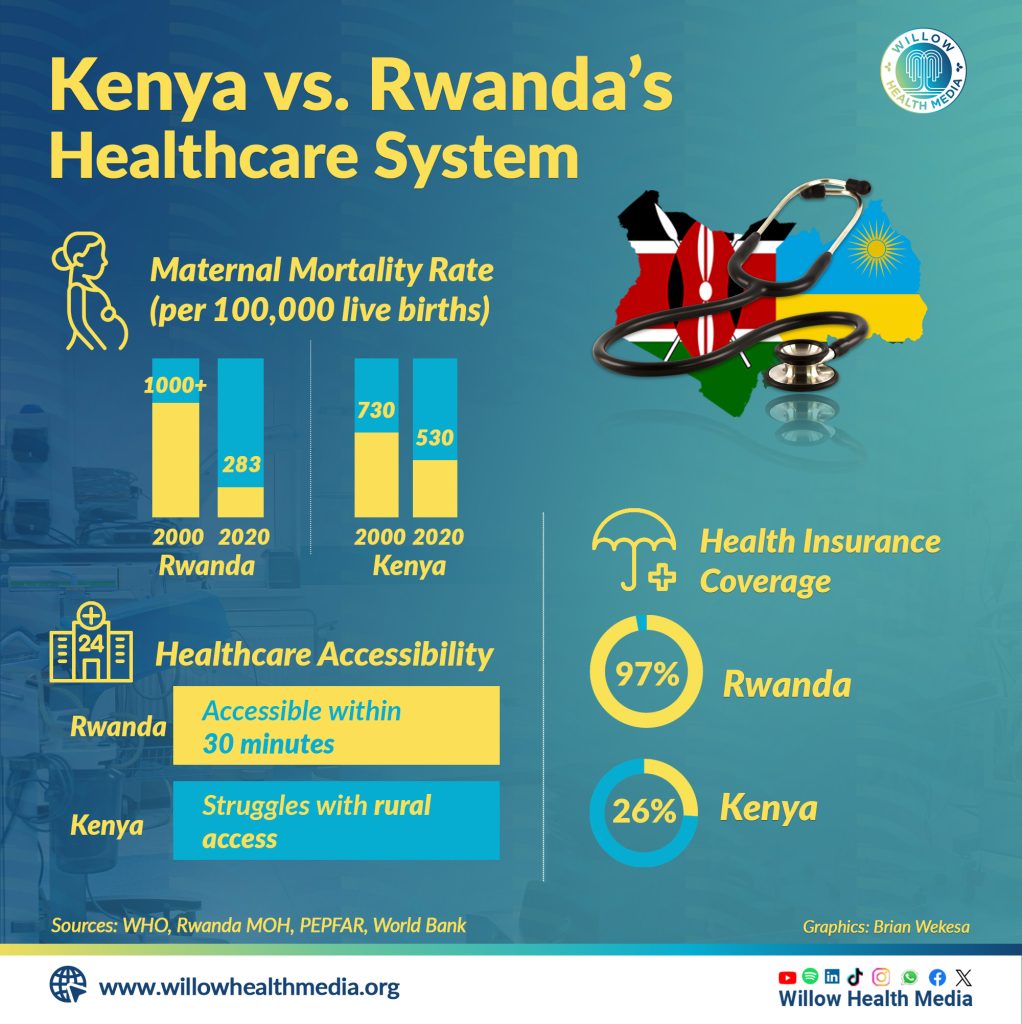

For instance, Dr Kabuteni pointed out that Rwanda saw a dramatic reduction in maternal mortality rates, from over 1,000 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to just 283 in 2020. This achievement was linked to government policies focusing on quality care and increased access to maternal health services.

Most vulnerable populations have access to healthcare

In contrast, Kenya continued to grapple with a high maternal mortality rate of about 530 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the World Bank’s data on maternal mortality ratios. This disparity highlighted the importance of strong policy execution and sustained investment in healthcare.

Rwanda has made tremendous achievements in ensuring that even the most vulnerable populations have access to healthcare. Dr Kabuteni explained that Rwanda achieved an impressive 97% health insurance coverage, with 93% of its population benefiting from the community-based health insurance scheme. The program guaranteed healthcare access for all, ensuring financial protection for low-income groups.

This approach contrasted with Kenya’s health insurance coverage, which remained low at 26%, according to the National Treasury data, leaving millions without health coverage.

Desta Lakew, the Group Partnership & External Affairs Director at Amref Health Africa, expressed admiration for Rwanda’s insurance coverage terming it “a testament to what African nations could achieve when they prioritized people over bureaucracy. African countries have an opportunity to learn and adapt these best practices.”

Rwanda focuses on five key pillars: people, infrastructure, equipment, systems, and governance

Kenya can learn from Rwanda’s model by expanding its community-based health insurance, strengthening subsidy mechanisms for low-income populations, and enforcing mandatory enrolment to improve coverage rates.

Rwanda’s Minister of Health, Dr Sabin Nsanzimana, highlighted the importance of structured health financing strategies. He noted, “We focused on five key pillars: people, infrastructure, equipment, systems, and governance. By reallocating funds wisely, we ensured long-term sustainability instead of short-term fixes.”

A case study from Rwanda demonstrated how the country identified $5 million (Ksh648 million) from short-term training budgets and redirected it to fund long-term medical training for essential personnel such as surgeons and midwives. This approach ensured a sustainable pipeline of healthcare professionals.

Rwanda’s deliberate effort to decentralize healthcare services improved accessibility. Community health workers managed over 70% of malaria cases, ensuring that healthcare services reached the grassroots level, according to Dr Nsanzimana. Additionally, Rwanda ensured that most of its 13.3 million population, according to the 2022 Census, could access a health facility within 30 minutes.

Through AI and telemedicine, specialists were accessible to every Rwandan, no matter where they lived

Dr. Nsanzimana explained, “We took healthcare to the people. You could not expect a mother in a remote village to travel for hours to see a doctor. Instead, we brought the doctor to her doorstep.”

Kenya, while having a devolved health system, faced challenges such as inadequate funding at county levels, poor coordination, and a lack of essential medical supplies in rural areas. By adopting Rwanda’s decentralized model, Kenya could improve access to primary healthcare and reduce pressure on referral hospitals.

Rwanda integrated artificial intelligence (AI) and telemedicine to bridge the healthcare workforce gap. Dr Nsanzimana noted, “Technology was no longer optional. AI and telemedicine transformed how we delivered healthcare, ensuring that specialists were accessible to every Rwandan, no matter where they lived.”

He further emphasized the urgent need for workforce development by highlighting the existing gap: “And we’re looking at the gap between the surgeons we have here, 162 versus the surgeons we need, 1,000. You see how big the gap is. So, if you make this balance, you could say, ‘This is impossible. I am giving up.’ Or ‘This is serious, and it requires a lot of effort and commitment.’ So, we are going to make it happen even if it seems impossible.”

Kenya, with its strong digital infrastructure, has the potential to implement similar innovations. However, the country needs policy reforms to encourage investment in health-tech solutions, particularly in remote and underserved areas.

Nyumbani Children’s Home in Nairobi relied on USAID support

The need for Kenya to reduce its reliance on donor funding became even more urgent following the recent USAID funding freeze. The suspension of aid programs affected crucial healthcare initiatives, including HIV treatment and malaria prevention.

Facilities like Nyumbani Children’s Home in Nairobi, which relied on USAID support for antiretroviral medications, faced uncertainty, with national antiretroviral stocks projected to last only six months.

The crisis underscored the vulnerability of Kenya’s health sector due to donor dependency and the need for sustainable, domestic financing strategies.

Kenya’s HIV program for instance is particularly donor-dependent and concentrated, with PEPFAR being the primary funder of Kenya’s HIV response.