Genetic testing revealed that Jabali had amyloidosis — a rare disease where abnormal proteins damage lungs, nerves, kidneys, heart, and digestive system. Now, ventilators, oxygen tanks, suction machines, and sterile medical supplies are part of the ‘home hospital.’

Susan Kanyiri works during the day but becomes an ICU nurse at night, caring 24/7 for her son Jabali. He was diagnosed with amyloidosis in October 2021, completely changing her life. Beyond the emotional burden came financial pressure: A month in the ICU cost Ksh6 million. Today, caring for him at home costs about Ksh100,000 monthly.

It started when Jabali was six months old. Susan noticed he was not developing normally. He couldn’t roll over, his lower limbs were weak and couldn’t bear weight, and his neck wasn’t strong. His development was slower than his older brother’s.

Susan, a pharmaceutical technologist, asked her aunties for reassurance. “And they’d tell me some babies just develop slower,” she recalls. “So, I brushed it off.”

Jabali’s condition shortly became life-threatening. His oxygen levels dropped to 35 per cent-far below the normal 100 per cent. He needed emergency transfer to the ICU. “He looked okay on the outside, but the gasping for air and his numbers told a different story,” Susan explains. “The doctors were shocked. They had to put him on oxygen immediately.”

The hospital ran every possible test, but nothing explained his condition. Susan was lucky to have a consistent medical team: a pulmonologist (lung specialist), cardiologist (heart specialist), nephrologist (kidney specialist) and neurologist (nerve specialist). They referred him for genetic testing, which cost Ksh50,000.

Amyloidosis mimics a variety of symptoms, and it’s easily mistaken for Sickle Cell Disease

Susan had never heard of genetic testing before. “At first, we were skeptical,” she admits. “What is genetic testing? We didn’t understand it, and it took time to even decide to go through with it.”

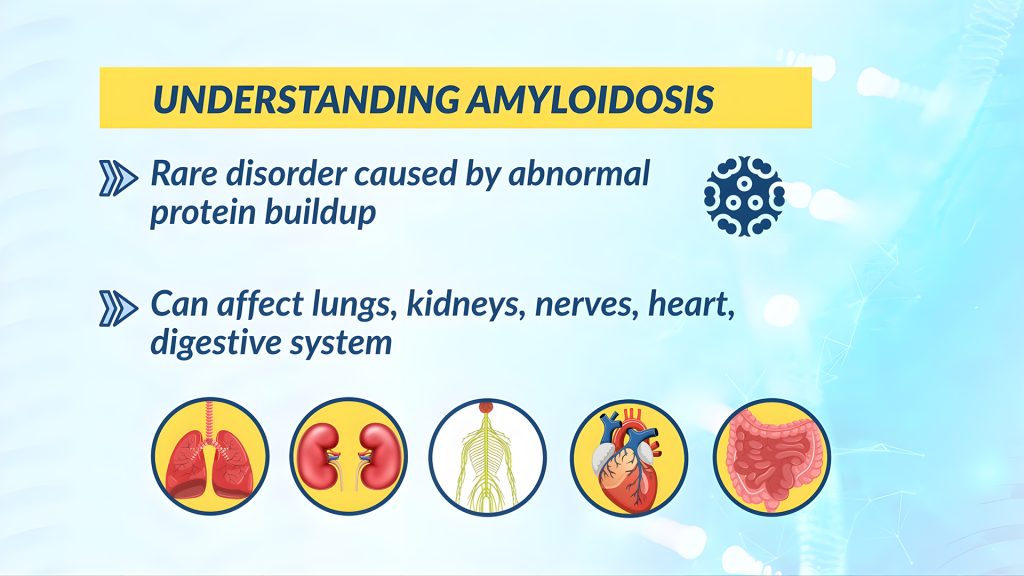

That test changed everything. Jabali was diagnosed with amyloidosis, a rare condition caused by abnormal proteins called amyloids building up in the body’s organs. These proteins interfere with normal function and can damage vital systems like the lungs, heart, kidneys, and nerves.

Dr Catherine Mutinda, a paediatrician and geneticist, explains that “Amyloidosis often mimics a variety of symptoms and tends to trigger strong responses to infections, making it easy to mistake for conditions like Sickle Cell Disease.”

Amyloidosis can be inherited or juvenile. Jabali has juvenile amyloidosis, which is extremely rare in infants with symptoms ranging from breathing problems to fatigue, muscle weakness and organ failure. It affects the lungs, nervous system, kidneys, heart, and digestive system. There is no known cure, only treatment focusing on symptom relief and slowing progression.

“His doctors tried to get a solution after so many tests, but nothing worked, and he was not improving,” Susan remembers.

In Jabali’s case, the condition severely affected his lungs and nervous system. He could no longer breathe on his own and needed mechanical ventilation. “The machine breathes for him,” Susan explains.

Jabali’s specialists include a pulmonologist, neurologist, ICU intensivist, speech therapist

“A multidisciplinary team for most rare disorders is the best approach,” says Dr Mutinda, “because things are changing fast and this helps the doctors lean on each other’s strengths.”

Jabali sees several specialists often: a pulmonologist, an ENT (ear, nose, and throat) specialist, a neurologist, an ICU intensivist (critical care specialist), a speech therapist, an occupational therapist, and a gastroenterologist (digestive system specialist).

Jabali, now three years and 10 months old, spent one month in the ICU. When he was stable enough for discharge, the family converted their living room into a home care ICU.

Ventilators, oxygen tanks, suction machines, and sterile supplies became part of their daily environment. Susan and a hired caregiver were trained by hospital staff on managing Jabali’s care, including maintaining hygiene and handling emergencies like power outages.

When the machine was taken for servicing, a replacement was hired for a daily rate of between Ksh5,000 and Ksh10,000, depending on where it was sourced. Similar measures were taken in case of any malfunction.

Susan has faced multiple emergencies. Like the day “The tracheostomy tube that connects to the ventilator came out, and the caregiver didn’t know how to put it back”, and she couldn’t reach Susan, who recalls “I was on a motorbike and couldn’t hear my phone ringing.”

Monthly expenses for Jabali come to about Ksh100,000 on the lower side

When she got home, Jabali was unresponsive, but the first aid she learned at the hospital helped, “and he came back.” Other emergencies were handled when “EMS Ambulance responded quickly and managed to stabilise him.”

Since most of Jabali’s critical care had been handled at the hospital, “We haven’t had medics coming home,” she says, as Jabali was usually admitted when things got serious, and he has been doing okay since April last year with one recent review.

Susan cares for Jabali at home by doing occupational therapy to help him with movement and daily activities, chest therapy to clear his lungs and improve breathing, and by giving him his medicine. “It’s expensive … very expensive!” she notes, putting monthly expenses for Jabali at about Ksh100,000 on the lower side.

“It’s like a small ICU at home, a small hospital at home,” she says. “We needed backup power in case the electricity went off. It’s expensive to power a generator.”

Beyond the emotional burden, the financial costs became overwhelming. The medical bill reached Ksh6 million after a month in the ICU. “Most insurance companies won’t cover rare genetic conditions,” says Susan. Even the insurer “who covered the initial admission only covered 50 per cent of inpatient costs or, in some cases, stops covering altogether once they learn the child has a chronic condition.”

She believes most insurers consider it too risky, “But I think it’s a misconception. We’ve stayed out of the hospital for over a year”, even as she clears the hospital bill in monthly instalments.

Susan became pregnant again. “I didn’t want anyone to know.” Jabali’s condition was genetic

The family has adapted to the new normal- having a mini-ICU at home. Siblings play with Jabali under careful supervision.

Dr Mutinda suggests practical solutions beyond financial aid, including providing essential medical equipment like the suction tubes Susan relies on, or covering critical expenses like electricity bills, vital to keeping life-support machines running.

Susan became pregnant again. “I didn’t want anyone to know,” she confesses. “Jabali’s condition was genetic, and I was scared it would happen again.”

She returned to her geneticist for testing and counselling, facing difficult ethical and emotional questions with her husband. “We were asking ourselves—after the testing, do we terminate? And I wasn’t ready for that.” Susan’s third son was born healthy and free of genetic complications.

Discovering Rare Disorders Kenya, a support community, helped Susan feel less isolated. Through the group, which has no membership fees, Susan connected with other parents. “For the first time, I didn’t feel alone” and they share critical resources like referrals to medics, affordable testing options, cost-saving tips and emotional support.

“It’s encouraging to know someone else understands,” says Susan, who now advocates for rare disease awareness and early genetic testing—especially if advanced screening was incorporated into antenatal clinics.

Jabali may never walk or speak, but his presence each day is a hard-won victory

Cultural stigma is one barrier to timely testing and treatment. “Some people are afraid to know the results. They ask, ‘What’s next if it’s positive?’ Not everyone is ready for the options that come after a diagnosis,” she says. “But we need to normalise these conversations and make support readily available.”

Susan advocates for:

- Wider access to genetic testing, especially during antenatal care

- Insurance reform to cover chronic and rare genetic disorders

- Public education to fight stigma and raise awareness

She wants to see a healthcare system that doesn’t abandon families just because a diagnosis is rare or complex. “People view these kids differently. These children are not a burden,” she insists. “They need a lot of love, care, and a system that supports them, especially financial support.”

Jabali may never walk or speak. But his presence, his breath each day he lives, is a hard-won victory. Susan has become more than a mother. She’s a caregiver, nurse, therapist, and a voice for others walking similar paths.