Research reveals Kenyans shun health insurance due to scanty knowledge of medical insurance, not seeing the need for it, loss of jobs. Others feel signing up is ‘too much work’

By Nancy Nzau

For donkey years, the late radio presenter Njambi Koikai endured thoracic endometriosis, a condition in which the endometrium tissue lining up the uterus migrates to the respiratory system.

Njambi, also a renowned reggae DJ braved over 20 surgeries before succumbing after a gruelling battle spanning almost two decades.

Like a majority of Kenyans, Njambi incurred catastrophic medical expenses that saw her turning to social media, not only to raise awareness but also to raise funds in 2018.

In her posts, Njambi lamented the lack of endometriosis specialists and to worsen the situation, “I don’t have medical insurance and my family have been meeting my hospital bills by the grace of God.”

Through a Paybill number, Kenyans raised over Ksh5 million for Njambi’s two-years-long treatment in Atlanta, USA, but she died this June from complications linked to the condition.

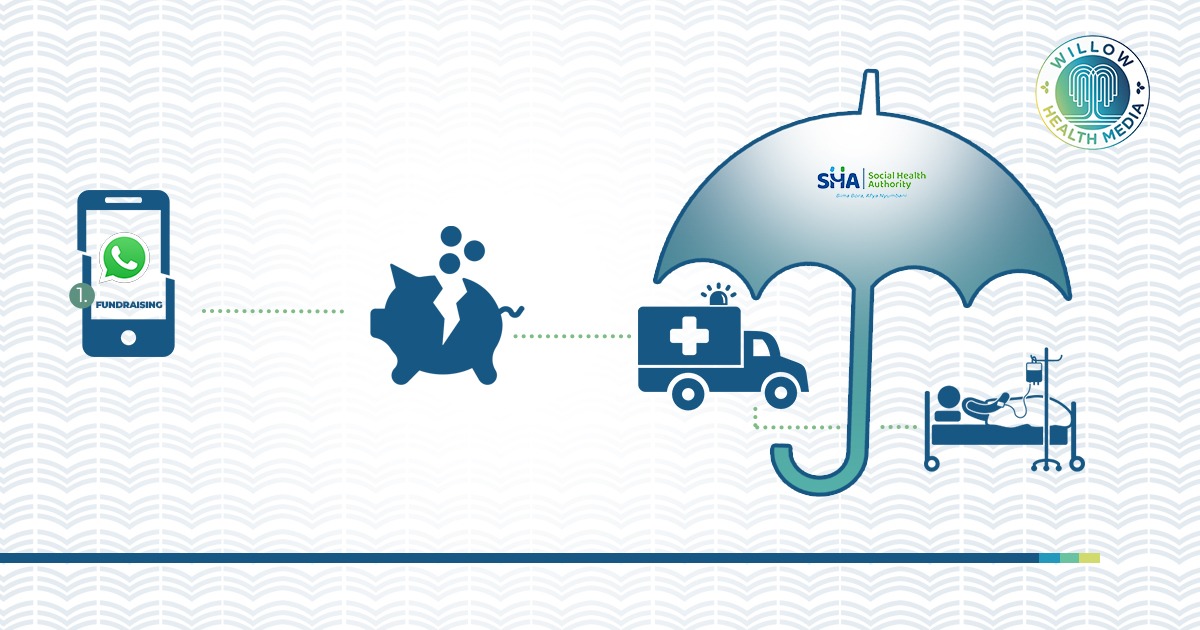

And just last month, Kenyans rallied to form a WhatsApp group after Sultana actress Winnie Ndubi Bwire aka ‘Dida’ made a social media medical appeal of Ksh5 million for her cancer treatment in Turkey.

Lamenting the high cost of healthcare in Kenya, Bwire noted that her family came through “where NHIF could not… because the medication is so expensive. Every 21 days I require Ksh100, 000.”

Bwire later died this September after a long battle with cancer.

While Njambi and Bwire had strong social media influence to raise funds, the same is not the case for millions of faceless Kenyans burdened by disease and blighting medical bills.

Take Beatrice Wayua, an 86-year-old widow in a remote village in Machakos County. She had been living with hypertension and heart disease for years before collapsing after supper.

Her granddaughter, Monicah Wayua, took her to a private clinic instead of a public hospital plagued by long queues.

Doctors said she had suffered a heart attack- and would suffer another. She was to be admitted immediately with a deposit of Ksh100,000 in the dead of night. Wayua, a stay-at-home mother and small-time farmer, had no medical cover.

As the family raised the deposit, Wayua suffered a second heart attack as the doctor had predicted-and died.

Why do Kenyans generally shun health insurance even when NHIF had base premiums of Ksh500?

Well, for starters, NHIF was a voluntary insurance fund and private covers are out of reach of most Kenyans.

NHIF data reveals that only one in four Kenyans or 26 per cent of the population, had some health insurance coverage. Among the 15 million insured, over seven million had dormant NHIF accounts.

One of the biggest reasons for this is that of over 15 million working Kenyans, only about three million are in formal employment-which includes a health cover. Of those, about 900, 000 are civil servants, according to the 2021 Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Financial Sector Deepening-Kenya in a study done seven years ago dubbed Shiling kwa Shilingi: The Financial Lives of the Poor, noted that rural communities depended on meagre earnings from agriculture with 36 per cent receiving additional income from relatives and friends. Most ‘farmers’ also had side hustles in domestic labour and construction.

Most dispensed with important expenditures in food, education and health: “ “Thirty eight per cent of respondents went without a doctor or medicine when needed” and barriers to healthcare could as little as not having Ksh20, noted the study.

This low incomes were another reason to the low uptake of health insurance with Ksh500 previously charged by NHIF monthly deemed as too high, according to a 2023 research by Beryl Maritim published in the International Journal for Equity in Health.

One respondent wondered whether after earning Ksh1,000 or Ksh500 within the month they should “pay NHIF and my kids to sleep hungry? They should put an amount where the low-level people can pay without struggling”

Such Kenyans relied on social networks for medical bills, but of their intriguing psychology, according to Shiling kwa Shiling study is that “people were more likely to contribute for a funeral than a medical bill” and that “funeral harambees raised money in a matter of days, for patients that may have been ailing for months.”

Another reason was lack of knowledge of medical insurance, not seeing the need for coverage, loss of jobs and feeling that signing up was ‘too much work’ and even those with NHIF memberships were not spared the indignity of medical appeals.

Sadly, NHIF, with its over 90 schemes, provided some financial risk protection for families, but it did not eliminate out-of-pocket payments and the need for fundraising.

Dr Daniel Mwai, an Advisor to the Presidential Economic Transformation Team on Health, told Willow Health that NHIF suffered ‘policy capture’ where most of its schemes despite being funded by the poor, the elderly and sickly had policies which mainly favoured strong interest groups- and not public interest.

NHIF, he argues, had Enhanced Schemes offering broader benefits to organized, often public sector workers, including civil servants, county government employees and state corporations, at the expense of the general public who had to put up with a limited scheme.

This ‘policy capture’ would ultimately lead many critically ill patients under the general cover to borrowing, selling off property and begging to cover their treatment. The inequity of the NHIF had the elites access to better healthcare services while the less advantaged were left to their means.

The World Bank noted this April that Kenya’s out-of-pocket spending stands at 22 per cent, which is high while a 2022 report on Catastrophic Health Expenditures and Impoverishment in Kenya, shows that out-of-pocket expenditure push1.48 million into poverty annually-with the hardest hit being the poorest households, the elderly, those affected by chronic conditions and in the rural areas, notes a 2018 research by a team of scientists led by Paolo Salari.

It is into this state of affairs that Universal Health Coverage (UHC) anchored on the principles of equity in health access and financing came into existence around 2005 during the World Health Assembly.

In an equitable health system, citizens access quality healthcare according to their needs but pay for services pegged on their ability to pay and in December 2012, the United Nations General Assembly asked governments to “urgently and significantly scale up efforts to accelerate the transition towards universal access to affordable and quality healthcare services.”

Over 30 middle-income countries, including Kenya, are implementing UHC whose “health agenda is crafted on solid principles that are globally acceptable,” says Dr Mwai adding that “The Social Health Authority (SHA) is the path to achieving UHC” under principles developed by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Dr Mohammed Abdi, the chair of SHA says the body will be the panacea to these challenges and that having health insurance should be non-negotiable as “lack of health insurance increases the risk of inadequate care for emergencies and chronic illnesses such as diabetes, and hypertension, which unmanaged, can lead to early death.”

Dr Abdi adds that such a scenario “leads to the progression of illness, which affects work quality and output, ultimately leading to a cumulative loss of national GDP and family income.”

The Social Health Act encapsulates three facets of healthcare needs to prevent financial hardships and encourage membership: Primary Health Care which is free, Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) bankrolled via a common pool of regular premium payments, deducted from salaries or paid directly and the Emergency, Chronic, and Critical Illness Fund will cover costs of managing and treating chronic illnesses after the patient’s SHIF cover runs out. It will also fund emergency treatment and will be funded by taxpayers and other sources.

The Primary Healthcare Fund, which is the most basic of all three funds, will cover inpatient and outpatient care services, screening and management of cancer, optical care, and end of life services. This will be available in Level 2, 3 and select Level 4 primary healthcare facilities.

The Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF) will cover inpatient and outpatient services; maternity, neonatal and child health services, renal care services, mental wellness, overseas treatment, and surgical services. It will also cover medical imaging, oral health services, and oncology services including screening and treatment of cancer. All these will be available at Level 2 to Level 6 facilities.

The third fund, which is the Emergency, Chronic and Critical Illness Fund, will cover ambulance evacuation services, accident and emergency services, admission in critical care units, palliative care and assistive devices such as wheelchairs. This fund will also provide management of chronic illnesses in Level 2 to Level 6 facilities.

“All these are positive strides towards eliminating out-of-pocket expenditure that pushes Kenyans to the point of borrowing for medical expenses,” says Dr Mwai.

And while NHIF contributions stood at Ksh500 on the lower side, SHIF has reduced contributions with a base premium of Ksh300. The government will also contribute to those who apply for subsidy if they fall below the threshold.

Further, SHA will also allow those unable to remit their premiums due to a sudden loss of income to pay back in small instalments.

“Premium insurance financing is not yet available but, will be after registration and final means testing,” says Dr Mwai.

“Emergency cases affected both the patient financially and the care providers as health institutions would end up accruing huge bad debts due to the obligation to address emergency needs, yet there wasn’t a robust emergency system,” explains Dr Mwai adding that it will be funded by the government.

Says Dr Mwai: “The SHA is inclusive for everybody and all Kenyans should be able to be members and should access services when they need them, no matter how poor, without experiencing catastrophic spending because of a disease. SHA addresses 70 per cent of our burden. We will continue to progressively include 30 per cent as we move forward. That way, no one is left behind.”

Dr Mwai is confident that the tariffs will increase as more Kenyans sign up and contribute to the pool as “the only way to have bigger and better tariffs is through increased citizen registration and premium payments to the fund.”