Chesikaki Secondary grabbed national attention when 54 girls fell pregnant in 2023. Today, it stands out as a model of teen mum reintegration, counselling, and mentorship through a ‘whole-school community approach.’

Angela Chelangat*, 17, is breastfeeding her one-year-old baby before boiling black tea, splashing her face with cold water and slipping into her school uniform inside a dimly lit mud-walled house in Chemondi village on the foothills of Mt. Elgon, where the air is crisp with dew-soaked grass and wood smoke.

“If I give up now, my child’s future dies with mine,” says Chelangat, who treks five kilometres uphill to St Thomas Aquinas Chesikaki Secondary School, but a motorcycle we had booked spares her the ordeal.

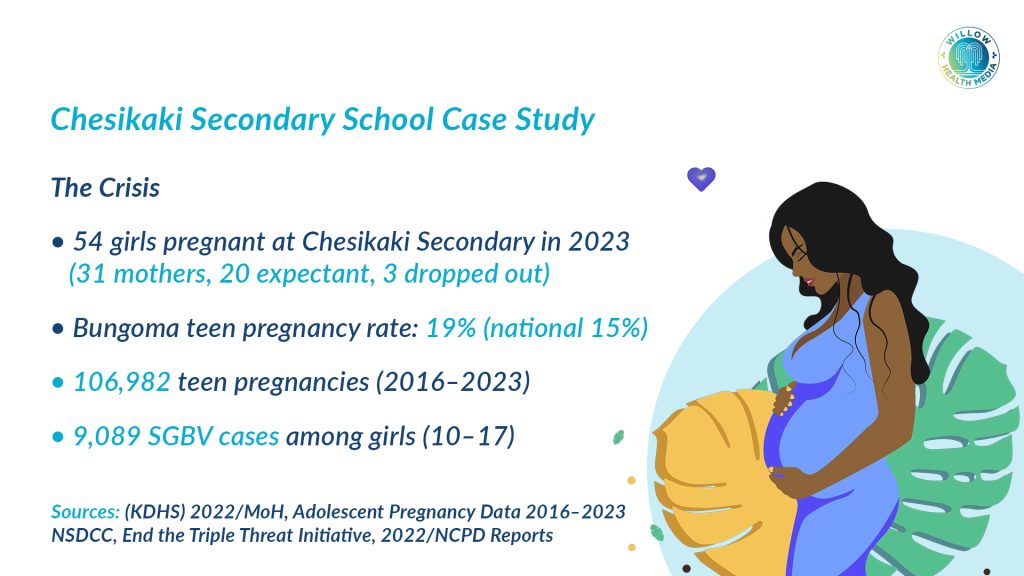

Chesikaki Secondary made national headlines when 54 girls got pregnant in 2023 alone. Thirty-one were already mothers, 20 were expectant, and three had dropped out.

The statistics reflected broken dreams, the persistent barriers of poverty, taboos, and silence around sexual and reproductive health.

Chelangat was among those who got pregnant in Form Two. Her boyfriend advised secrecy until after delivery, but fear and shame almost drove her to an abortion, landing her in the hospital, which was how her mother, Gladys Temuko, found out.

Unlike her peers who dropped out, Chelangat, who dreams of becoming a CRE and Kiswahili teacher, was given a second chance. “I leave my baby in my mother’s care and breastfeed in the morning and evenings after classes,” as her mother urged her to “return to school and realise your dreams.”

My mother fed my baby, while school offered me counselling and sanitary pads

“I was devastated,” Temuko told Willow Health Media. “I had struggled so much to keep her in school. But I told myself, “I must stand by her,” after she tearfully pleaded and sought forgiveness for letting her down.

Chelangat is not alone. There is also Evelyn Nafula*, who recalls, “I was in Class Eight when I got pregnant” through a boyfriend she met during a sports event. She was 16, and lived with her stepsister in Mt Elgon while her mother worked in Kitale.

Nafula was about to sit for her KCPE exams in 2022, but her mother insisted she must continue, and, after passing her KCPE, she enrolled at St Thomas Aquinas Chesikaki Secondary. “My mother would wash the baby, clean his clothes, and feed him milk,” while the school offered counselling sessions and sanitary pads.

But balancing motherhood and academics has been tough. “We keep pushing on,” says Nafula, who adds that while some classmates understand, others mock her.

Her mother discouraged abortion, reported the matter to the school, chief and police

“Being a mother and a student has not affected my performance too much because my mother does everything for my child.” But at home, life is still hard. Her father died when she was nine, leaving her mother, a casual labourer, to fend for the family. Now 19 and in Form Three, Nafula dreams of becoming a doctor.

For Faith Chepkorir* from Kimama village in Cheptais, Mt Elgon County, pregnancy came in Form One at the height of Covid-19 disruptions in July 2020. Her mother, Hellen Juma, a midwife, discouraged her from seeking an abortion and instead reported the matter to the school, the area chief and police.

But the nine kilometres to Chesikaki Secondary forced her to stay home until she delivered at Cheptais Sub-County Hospital in April 2021.

Chepkorir, supported by her mother, who “sold vegetables to pay my school fees even when my father opposed the idea,” repeated Form One with the August 2021 intake and progressed to Form Four.

Despite stigma and financial strain, Chepkorir scored a C– (minus) in 2014 and hopes to study nursing at the Kenya Medical Training College. Her child, now in PP1, continues to be cared for by her mother after her secondary school boyfriend “only came once in hospital with KSh700 and disappeared to date.”

Greatest challenge has been my husband who dismissed the pregnancy as not his problem

While some former classmates mocked her, teachers and the guidance and counselling department supported her. “I made new friends, focused on my studies, and that kept me going.” Her mother says, “The greatest challenge has been my husband. He dismissed the pregnancy as not his problem. I believe education is the best gift I can give my daughter.”

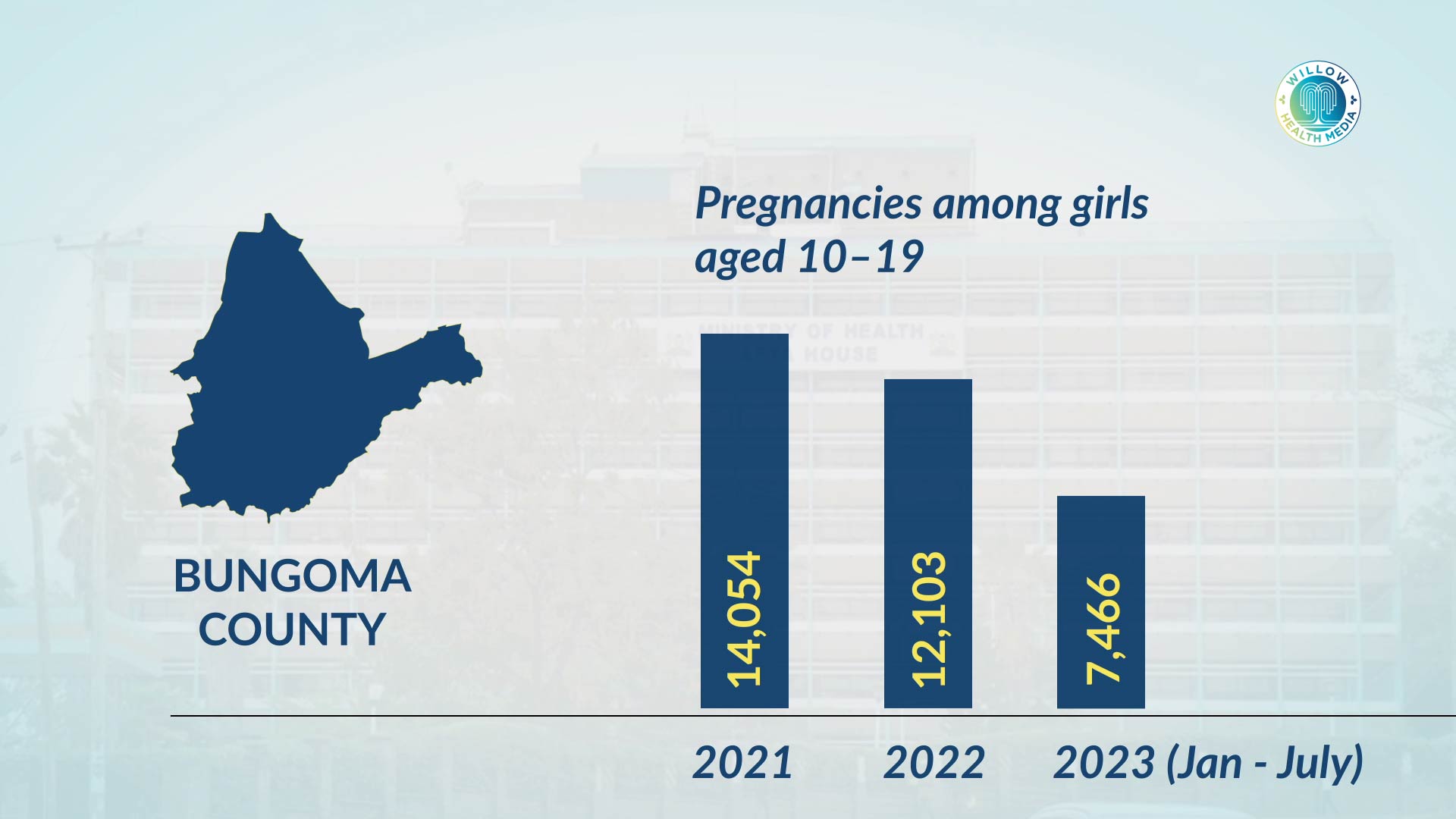

In Bungoma, the teenage pregnancy rate is 19 per cent, far above the national average of 15 per cent, according to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) 2022 report. According to the Ministry of Health, Bungoma recorded 14,054 pregnancies among girls aged 10-19 in 2021, 12,103 cases in 2022, and 7,466 cases between January and July 2023.

Cumulatively, between January 2016 and August 2023, Bungoma County recorded 106,982 pregnancies among girls aged 10-19. Between 2016 and July 2023, the county recorded 9,089 cases of sexual and gender-based violence involving girls aged 10-17, compared to 18,510 cases nationally.

Kenya continues to battle the “Triple Threat” of HIV, gender-based violence (GBV), and adolescent pregnancies, which remain dangerously high despite slight declines in some areas. Bungoma ranks among the most affected.

The National Syndemic Diseases Control Council (NSDCC) is driving the End the Triple Threat Initiative, launched in 2022, to coordinate government and stakeholder responses through county-led, multisectoral approaches.

Health service gaps, high GBV rates and dwindling donor funds remain obstacles

The strategy aims to empower youth, strengthen health systems, and close policy gaps with the goal of eradicating the threat by 2027. However, persistent health service gaps, high adolescent pregnancy and GBV rates, and dwindling donor funding remain obstacles.

To address the teen pregnancy crisis at Chesikaki Secondary, the Ministry of Health partnered with the National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) and community leaders. Their interventions included counselling, psychosocial support, reproductive health education, and reintegrating teen mothers into school.

Two years later, the young mothers are thriving, and the school is now a model of excellence for others to follow.

Guidance and Counselling teacher Joan Mabonga cites mentorship programmes, the Mount Elgon Jilinde initiative, Visionary Ventures and mental health groups for the turnaround.

But challenges remain, including long commutes. “Some pregnancies occur along these routes,” says Mabonga. “Parents believe their daughters are in school, only to discover they never made it to class.”

Mabonga also notes that poverty drives vulnerability. “Many parents cannot provide basic items like sanitary pads. This dependency exposes girls to sexual exploitation.” Partner organisations distribute pads- at least one pack per girl each month.

Some teen mothers have progressed to TVETs, colleges and universities

For learners with guardians or those who are orphans, parental involvement is even lower. “Many parents are unwilling to attend meetings or engage when called upon,” Mabonga adds.

School principal Paul Boyo recalls students confessing they saw pregnancy as a way to escape menstrual stress. “With steady supplies of pads, this dangerous coping mechanism faded.”

From 54 cases in 2023, Chesikaki recorded only two new cases in 2024. However, traditional circumcision ceremonies later fuelled a spike of 11 pregnancies.

Even so, Boyo says progress is undeniable: absenteeism has reduced, hygiene improved, and some teen mothers have progressed to TVETs, colleges, and universities. “Teenage mothers can still make it if given a second chance.”

The school now needs a safe house, better facilities, and a steady supply of pads.

Bungoma Deputy Governor Janepher Chemtai Mbatiany, from Mt Elgon, saw firsthand how “girls were marginalised, remained at home while boys went to school, and were married off young.”

Bungoma now has a GBV policy, promising safe houses within health facilities and a gender recovery centre with nurses, doctors, social workers, and counsellors. She says Chesikaki’s success will be replicated in other schools by integrating health, education, and gender departments.

Chesikaki now a model centre in tackling adolescent pregnancy, HIV and GBV

Cheptais sub-County Director of Education, Emily Isiya, said the girls who became pregnant in 2023 received support. Many returned to school, took final exams, and are now heading to universities or technical colleges. Most had been victims of poverty that “pushed them to seek help from boda riders and older men. If parents provided for their daughters with food, clothing, and sanitary pads, such temptations would be fewer.”

The NCPD now plans to scale up the Chesikaki model to other counties. Director General Dr Mohamed Sheikh calls Chesikaki a centre of excellence in tackling the “triple threat” of adolescent pregnancy, HIV, and GBV under a “whole school community approach.”

“It has shown us what is possible when government agencies, schools, parents, and community leaders come together,” Dr Sheikh says. “Every stakeholder has a role, and their buy-in makes programmes sustainable.”

Dr Sheikh explains, “The Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2022 shows that 68 per cent of girls and half of boys receive reproductive health information from peers. Structured mentorship ensures accurate information is passed on.”

Yet challenges persist. “The unmet need for family planning has risen to 14.2 per cent, and in 2024, more than 230,000 adolescents aged 15–19 became pregnant. Counties such as Nairobi, Kakamega, Bungoma, and Narok each reported over 10,000 cases,” he says.

While abstinence and life skills remain the government’s frontline strategy, Dr Sheikh stresses the need to dispel myths and stigma. Scaling up the Chesikaki model nationally, however, faces funding constraints.

For sustainability, NCPD is linking education, health, and environmental well-being through initiatives like Global Health Promoting Schools and the “Adopt a Fruit Tree” programme.

“Ending teenage pregnancy is not about one intervention; it is about all of us pulling together,” he says. “Chesikaki has given us a blueprint, and now we must take it further.”

NB: Names have been changed to protect identity.

A 17-year-old pregnant girl in Nairobi, orphaned and uninsured, is turned away from several clinics because she has no guardian, no money, and no SHA cover.

Her struggle shows how teenage mothers often face impossible barriers to basic care, a sharp contrast to places like Chesikaki, where structured support gives girls a fighting chance.