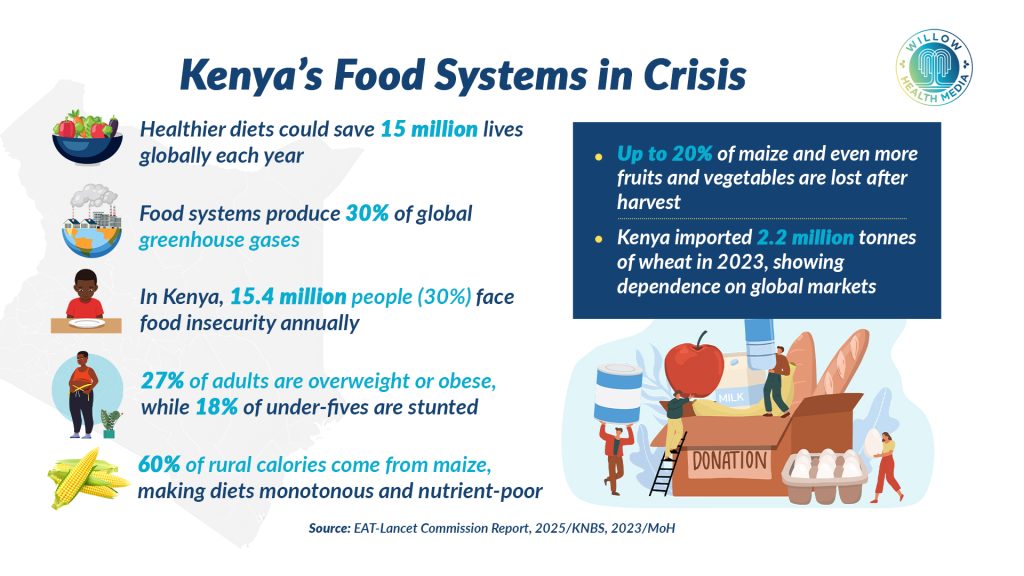

Over 15 million Kenyans lack enough food annually, yet lifestyle diseases linked to poor diets are on the rise. But aligning food policy with health and the environment could save millions of lives, and trillions in global investments.

A simple change to our diets could prevent 15 million early deaths annually and help repair the damage food systems cause the environment, according to the findings of a new report.

The 2025 EAT-Lancet Commission Report, dubbed, Healthy, Sustainable, and Just Food Systems, released last week, warns that the way we produce food is also making people sicker and poorer, especially in Africa, where hunger and malnutrition persist even as diets shift toward processed foods and sugar-heavy products.

In Kenya, for instance, climate change has exacerbated hunger, and many people depend on livestock for their income. The question is whether the country builds a healthy, fair, and sustainable food system. Data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) reveals an urgent situation: 30 per cent of Kenyans, or 15 million people, don’t have enough to eat annually.

Yet, lifestyle diseases linked to poor diets are on the rise. The Ministry of Health says about 27 per cent of Kenyan adults are overweight or obese, with cases of diabetes and hypertension increasing rapidly in urban areas.

The report states that less than one per cent of people in the world live in a “safe and just space,” where everyone has enough food without harming the planet. It warns that food production creates nearly a third of the world’s pollution and is the main driver of environmental damage like wildlife loss and polluted water.

“The evidence is undeniable. Transforming food systems is not only possible, it’s essential,” said Johan Rockström, Commission Co-Chair and Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “What we put on our plates can save millions of lives, cut billions of tonnes of emissions, halt biodiversity loss, and create fairer food systems.”

Kenya’s agriculture faces land fragmentation, erratic rainfall and soil degradation

Kenya’s food system illustrates the tension between health, environment and livelihoods. Agriculture is the backbone of the economy, contributing about 21 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employing 57 per cent of the population, according to KNBS.

However, the sector faces declining productivity due to land fragmentation, erratic rainfall, and soil degradation. At the same time, rising urbanisation has seen a rise in consumption of processed foods, meat and sugar.

Kenya’s dietary inequality is such that the middle- and high-income families in Nairobi, Kisumu and Mombasa consume more red meat, dairy and processed foods, while poor rural households subsist on maize-based diets with little diversity.

KNBS notes that maize accounts for more than 60 per cent of daily calorie intake in many rural households, contributing to malnutrition, especially among children.

The 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey found that 18 per cent of children under five are stunted and five per cent are wasted due to poor diets. In contrast, the Health Ministry says 27 per cent of adults are overweight or obese, showing Kenya’s growing double burden of undernutrition and diet-related diseases.

Droughts ruined crops for 4.4 million people, floods wiped out farmlands in Western Kenya

“Transformation must go beyond producing enough calories,” said Shakuntala Haraksingh Thilsted, the Commission’s Co-Chair and Director at Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). “It must guarantee the right to food, fair work, and a healthy environment for all.”

The Report warns that even if the world transitioned fully away from fossil fuels, food systems alone could still push the planet beyond the 1.5°C warming threshold.

In Kenya, climate change is devastating farms. Recent droughts ruined crops for 4.4 million people, and this year’s floods wiped out thousands of hectares of farmland in Western Kenya, according to KNBS.

The report sets out eight solutions to guide global transformation: Protecting and promoting traditional healthy diets, reducing food loss and waste, and adopting sustainable production practices.

Kenya loses about 20 per cent of its maize harvest to poor storage and post-harvest handling, according to KNBS, while fruits and vegetables also suffer high spoilage rates before reaching markets.

Deforestation in Mau reduced water flows in Mara and Sondu rivers, disrupting ecosystems

Cutting these losses could significantly improve food availability without putting more strain on land and ecosystems.

The Report also calls for stopping agricultural conversion of intact ecosystems, a challenge Kenya faces as farmers expand into wetlands and forests. For instance, deforestation in the Mau Forest has reduced water flows feeding the Mara and Sondu rivers, disrupting ecosystems and communities downstream.

Sustainable intensification, soil conservation and agroforestry are among the practices that could help Kenya meet its food needs without further ecological damage.

“The Planetary Health Diet remains a powerful tool to improve health and cut environmental impacts,” said Walter C. Willett, Commission Co-Chair and Professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “But transformation must happen across the whole system. Governments, businesses, civil society, and individuals all have a role.”

Kenya has tried various policies to improve diets and protect the environment. The government has made food security a priority, but experts say progress has been mixed.

Kenya imported 2.2 million tonnes of wheat, making families vulnerable to international price spikes

For example, the Health Ministry encourages people to eat traditional, nutrient-rich vegetables like amaranth and spider plant, which can survive harsh weather. However, these healthy foods are still less popular than staples like maize and wheat.

This reliance on imported wheat is a problem. Kenya bought 2.2 million tonnes in 2023, making families vulnerable to international price spikes. At the same time, local farming of drought-resistant grains like millet has stalled.

This situation makes the global report’s advice to revive traditional diets highly relevant for Kenya. Despite all these efforts, the people who grow and sell our food often struggle to make a living, with nearly a third of food workers worldwide earning less than they need to survive.

In Kenya, smallholder farmers, who produce 75 per cent of the country’s food, face low prices, poor market access, and high costs. The Report recommends ensuring these farmers get decent work and a voice; a transformation that would save lives, protect nature, and be highly profitable.

Kenya struggles with rising diseases, ongoing undernutrition, worsened by climate change

It estimates global gains of $5 trillion per year from better health and ecosystems is over ten times the investment required. For Kenya, aligning food policy with health and the environment could pay off in both human and financial terms.

However, the path is challenging. Changing diets isn’t just about awareness; it’s about cost and access. For many Kenyans, healthy foods like fish, fruit, and dairy are still too expensive. The report calls for financial incentives and policy reforms to make healthier choices easier.

Kenya’s situation shows why this is urgent. The country struggles with rising diseases and ongoing undernutrition, worsened by climate change and economic inequality. The global report provides a blueprint, but local success will need political will, investment, and community effort.

As the Commission’s Johan Rockström warned, “What we put on our plates can save millions of lives, cut billions of tonnes of emissions, halt biodiversity loss, and create fairer food systems.” For Kenya, the message is clear: the future of its people, climate, and economy depends on rethinking food from farm to fork.