Powered by AI and mobile money, the Tap2Eat innovation enables pupils to ‘order’ porridge and food, which for the needy and vulnerable could be the only meal that day.

Every lunchtime, a child at a Kenyan primary school uses an orange wristwatch to instantly order and receive a hot lunch from a food station tucked within the school compound.

This system, called Tap2Eat, was created by Food4Education, a school feeding enterprise that provides hot, nutritious meals to needy children in public schools and uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) and mobile money to provide the only daily meal for some children.

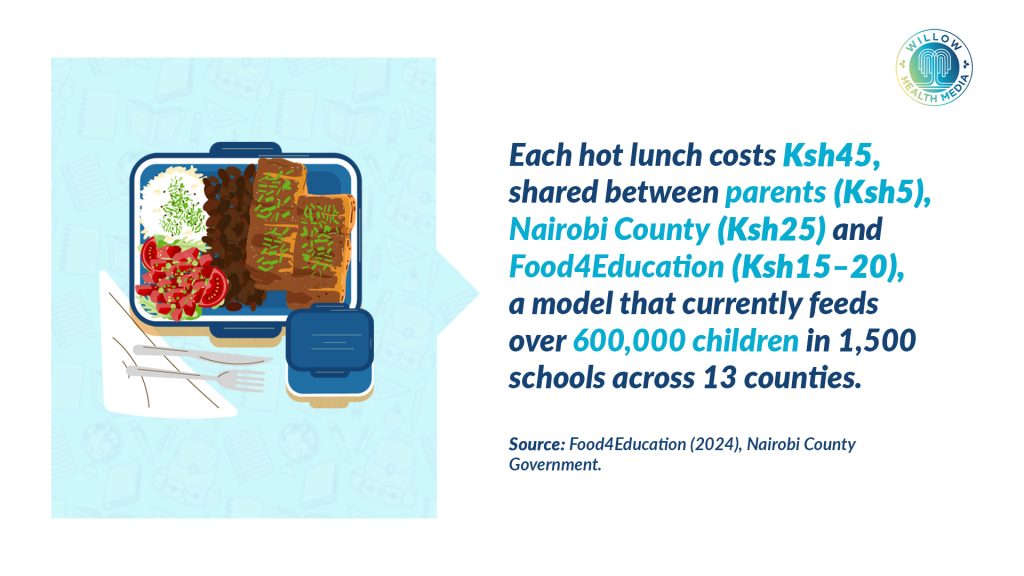

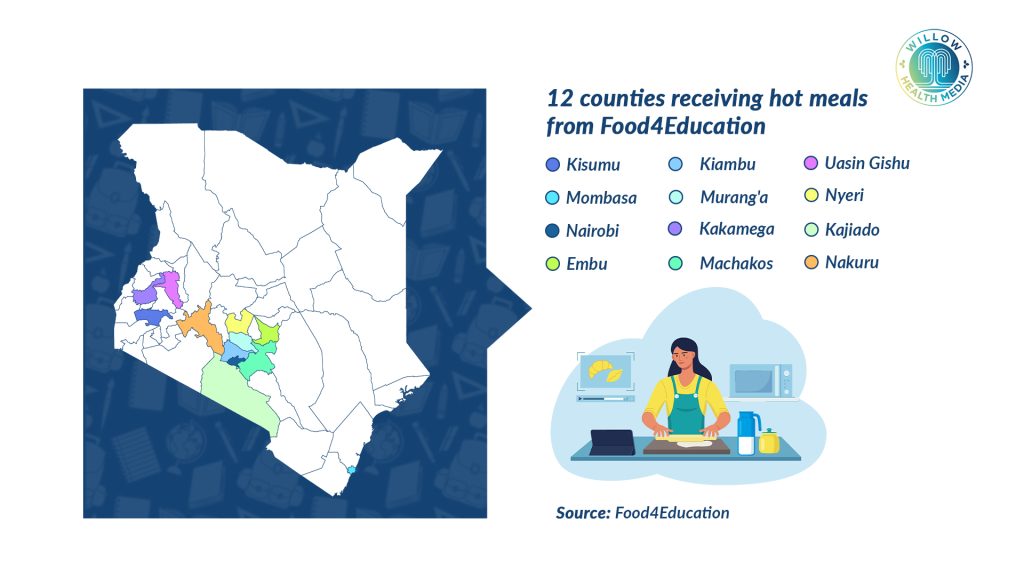

Since its inception, Food4Education has delivered more than 150 million meals in 1,500 schools across 13 counties in Kenya, “because we strongly believe no child should go to school hungry,” said Food4Education founder and CEO, Wawira Njiru.

They serve two meals made from over 20 recipes: a lunch of rice with beans and vegetables, and a nutritious break-time porridge fortified with vitamins for pre-primary children aged between three and five.

Food4Education’s large kitchen prepares more than 65,000 of these meals daily.

Stephanie Atika, the Growth and Operations Manager, said the meals are spiced differently in different regions to match local tastes, such as using masala in Mombasa and turmeric in western Kenya. The vegan meals are designed to be both tasty and nutritious.

We serve 200 grammes of rice and 350 grammes of stew for lower-grade learners

Once a school is enrolled on the feeding programme, each child’s height, weight, and health are checked to ensure the meals meet the specific nutritional needs of the children in that area. Atika said learners in Embu and Murang’a counties receive fortified porridge, while those in other counties receive lunch meals.

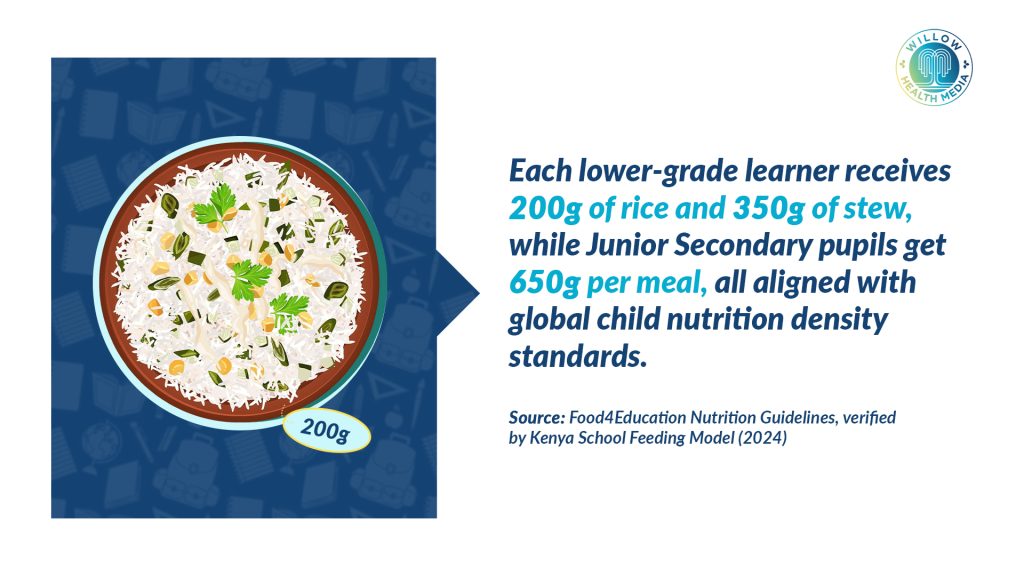

“We serve 200 grammes of rice and 350 grammes of stew for lower-grade learners as per the globally stipulated nutrition density of a meal for children of a certain age,” she said. “Learners in Junior Secondary School get 650 grammes because they are adolescents and therefore require more energy for growth.”

Carefully tracking data has helped cooks and servers in the schools reduce food waste to one per cent, down from an average of 40 per cent. For children who can’t afford the Tap2Eat wristwatch, sponsors like the French government help cover the cost.

Wawira said that besides ending hunger and malnutrition, the school feeding program has helped restore dignity by creating employment for over 4,000 people, of whom 80 per cent are women.

Food4Education is not the first school feeding program implemented in Kenya. Similar programs began in the late 70s with ‘Maziwa ya Nyayo’, piloted by then President Daniel arap Moi, where school children received small packets of milk to encourage school attendance.

The main challenge is maintaining funding and continuity when politics change

The popular initiative, which ran for 20 years, ushered in another program by the World Food Programme (WFP) targeting primary school children in arid and semi-arid lands, and in urban informal settlements.

This was boosted by the Free Universal Primary Education Program launched by then President Mwai Kibaki, which saw an increase in school attendance and retention via receiving food even during school holidays, especially for children from needy backgrounds.

However, as Kenya attained middle-income status, the WFP feeding programme was handed over to the government. Last year, Nairobi County governor Johnson Sakaja launched the popular Dishi na County, a free lunch initiative for children in county public schools, for whom parents chip in Ksh5 each to the kitty.

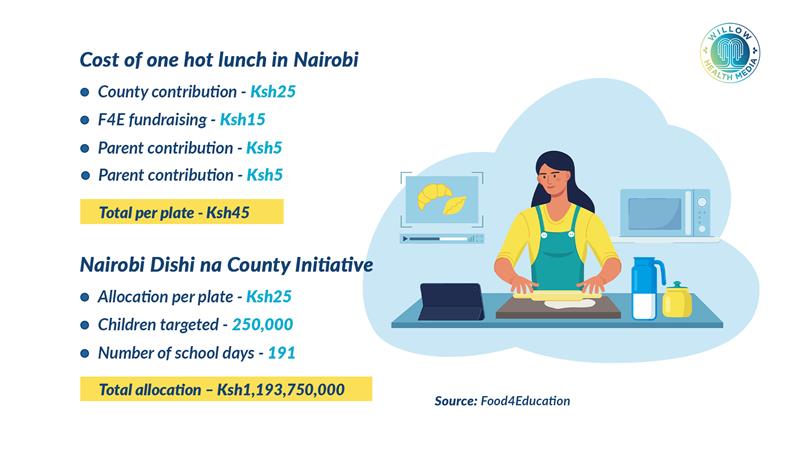

Food4Education, working in partnership with the Nairobi county government, estimated the cost of one plate of lunch at Ksh45. To cover this cost, the county pays Ksh25 per plate, parents pay Ksh5 each, and Food4Education tops up the remaining Ksh15-20 depending on food cost fluctuations. But its sustainability beyond Sakaja’s political tenure is still hazy.

Shalom Ndiku, Food4Education’s director of public affairs, said the main challenge for such programmes is maintaining funding and continuity, especially when politics change, competing priorities or when budgets are tight, especially in counties.

One solution is ringfencing school feeding budgets at both county and national levels

Ndiku lists policy and legal frameworks specific to school feeding that are sustainable beyond political cycles as one solution, buttressed by ringfencing school feeding budgets at both county and national levels to guarantee sustained financing.

Already, a coalition of non-governmental actors has developed a model school feeding policy to standardise allocations and implementation across counties.

The Food4Education model provides a benchmark for alleviating classroom hunger in Africa.

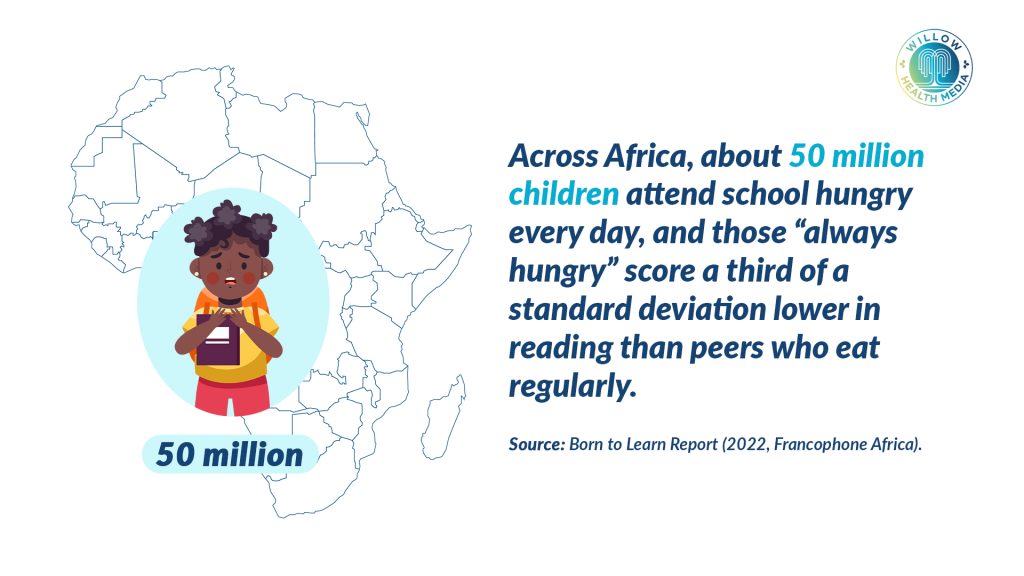

A 2022 francophone report titled, Born to Learn, showed that about four in 10 primary-school students report being “often or always” hungry while at school. In Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), one in three students said they are “always” hungry at school.

The study found that those “always hungry” at school have reading scores lower by about a third of a standard deviation, compared to those who never report hunger; while those who are “often hungry” score lower by about one-fifth.

School feeding programme has seen an increase in school attendance and exam performance

Food4Education reports that out of about 90 million school-going children in school in Africa, about 50 million show up to class hungry daily, while about 60 million children are at risk of going hungry in school.

However, the school feeding programme has seen an 8-10 per cent increase in school attendance, a 20 per cent increase in performance in national examinations, and better health outcomes from the enrolled children. Moreover, children who eat at lunchtime are found to get about 3 to 4 extra hours of education compared to those who don’t.

“That’s why we must have government buy-in and ownership by everyone,” said Wawira. “This is the only sustainable path, especially in light of recent cuts in donor funding.”

Food4Education now targets to feed one million children daily by 2027 and venture into other African countries, starting with Zambia.

“School feeding is a shared responsibility between parents, the government and the public because it keeps children in school, and society benefits from the jobs created from the programs,” said Wawira who stressed that to be sustainable, the programme must rely on local parents and the government, not just outside donors “because when donors pull out, the whole programme can collapse.”