In past years, touching the ear was enough to get a child enrolled and tall ones joined school when not ready or fully developed

Ann Wanjui’s second-born son was a quiet toddler glued to cartoons on television, until playgroup changed everything. At two years, eight months, he blossomed: making friends and gaining confidence.

His story reflects a growing trend among Kenyan parents enrolling children barely off their diapers into early learning. This has sparked debate about the right age to start school against family bonding, educational stimulation and working parents juggling childcare needs.

Indeed, the traditional model of children staying home until age four is being challenged by practical realities and emerging research on early childhood development.

Take Wanjui’s son. He spent his days glued to cartoons. His speech and cognition lagged, and he cried most mornings watching other children board the school bus. The isolation was taking a toll. Wanjui knew things had to change.

She started potty-training him and so did the school which finally agreed to admit him and, “After a week, I realised he did not want to wear a diaper during the day. By week two, he wanted to use the potty by himself, and now I only buy diapers for the night,” says Wanjui, who lives in Kajiado County but works in Machakos County, commuting daily to work.

The transformation was swift for the son. His speech improved. He became more social, loved teachers, and enjoyed picture books. His elder brother started school at three years old. But the younger one reached important milestones faster.

“She has also learned to speak better and can say, ‘Mum, the food was delicious'”

For Wanjui, structured early learning had more benefits than at home. “The house girl put him in front of the TV, and I would find him very tired, moody and bored. But in school, he learns social skills interacting with others.”

With other children, toys and play items, he adapted quickly. The social environment proved proper for his development.

Dr Peninah Musyoka’s third-born daughter started school at two years eight months. Unlike her elder two sons, who took longer to join the playgroup. The little girl reached milestones faster as “she could speak some words, feed herself, was very independent, always happy and excited about school,” says Dr Musyoka. “She has also learned to speak better and can say, ‘Mum, the food was delicious.'”

Dr Musyoka focused on specific developmental goals rather than academic achievement. The same was not the case with her other children, as by the time the first son enrolled in school, “he could not name a spoon, feed himself.”

Dr Musyoka gradually realised that allowing him to stay home alone with the nanny “was not helping much, and he was not getting the right stimulation.”

Her second child, born during the Covid-19 pandemic, also spent a longer time at home due to pandemic restrictions, resulting in limited social interaction, thus affecting his development.

If your child recites numbers and alphabet after a few weeks, then schooling is harmful

Dr Musyoka lists childhood infections among the effects of early schooling, but it helps in building immunity, and in any case, early enrollment developmental benefits outweigh the temporary health challenges.

Phyllis Munyi, Founder of Dyslexia Organization Kenya and Director of Rare Gem School for Children with Neurodiversity, says early schooling has its pros and cons. Parents should thus identify a playgroup, not a formal class.

“If your child comes home reciting numbers and the alphabet a few weeks after joining school, then that is doing more harm to the child than good. But if the child comes back home singing more songs, can colour, and is toilet-trained, then that is a good sign,” she says.

While formal schooling starts at age four, playgroup focuses on play, colouring, interaction, not numbers or letters. These activities build skills for future learning without the pressure of formal instruction.

Munyi warns that children who begin formal learning very early may get bored as their minds aren’t fully developed for advanced studies. This can create long-term negative associations with education.

Also, being detached from families while learning about others in school creates social expansion, which though beneficial in other ways, can affect family bonding “And mothers will not have learned their children as well, like their temperament,” says Munyi.

Children with autism calm down after mixing with others in a structured environment

For children with special needs, early school exposure can be particularly beneficial. Teachers often notice missed milestones, providing parents with valuable insights and help.

Munyi cites children with autism, who often have meltdowns at home, can calm down after mixing with others in a structured environment that regulates their behaviour.

Dr Supa Tunje, a Child Development Paediatrician, emphasises security, safety, nutrition, responsive caregiving, and good health before considering school.

She warns that early schooling doesn’t necessarily mean early learning opportunities if the interactions are not meaningful and developmentally appropriate.

Dr Tunje further explains that home environments can be equally enriching if properly structured.

“The same environment that you are looking for in a school can be created at home by providing play items, engaging the child during playtime, removing the screen, and ensuring that they gain the developmental milestones that would have led you to take them to a school environment.”

Age should not worry parents; rather, having independence, toilet-training, and communication skills are better indicators of readiness to start school.

What happens to parents in poor slums or rural areas who cannot afford daycare and early schooling?

Most parents consider location, meals, educational activities, and trained caregivers

Well, while there are informal daycares in such areas, parents might consider subsidised ones run by county governments, which charge Ksh50 per day, which is what is charged at informal daycares in the urban informal settlements.

A study by Global Citizen in Nairobi’s Korogocho slum pegged the average monthly cost of full-time daycare at Ksh335. This contrasts with the Ksh200-1,500 per day charged by professional daycares in urban areas caring for one- to five-year-olds for half a day, according to Bestcare Facilities Management.

Full-time daycare for 3-month to 6-year-olds can cost Ksh300-3,000 per day or Ksh30,000-90,000 per term, while night care costs Ksh1,000-3,500 per night.

Most parents consider location, meals, educational activities, and trained caregivers, besides extracurricular activities and transport for an additional fee.

The intersection of individual development and institutional capacity creates unique challenges for early childhood education in Kenya. While some children thrive in early school settings, others may benefit more from extended family-centred care.

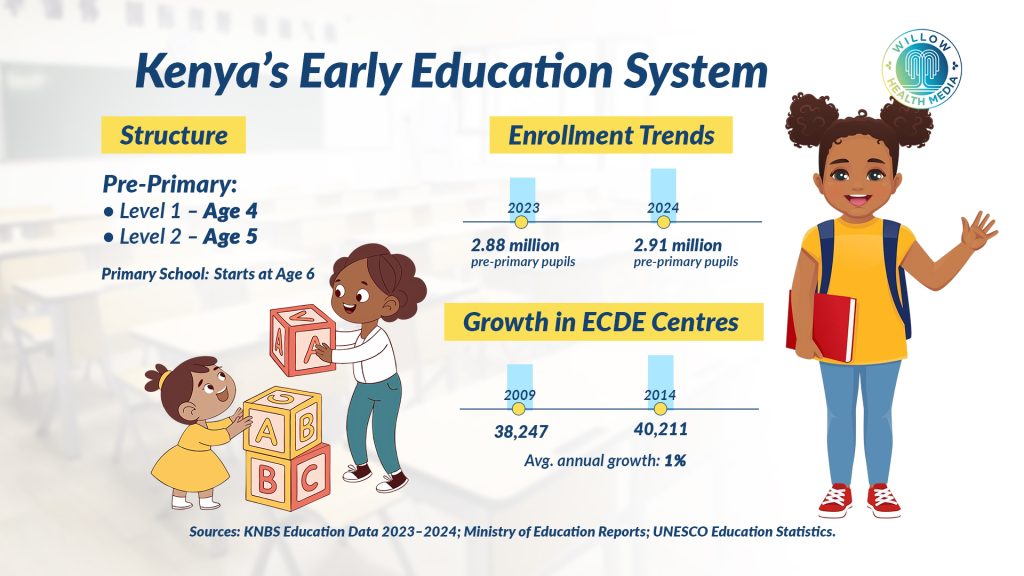

Kenya’s 2017 Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy highlights the critical first 1,000 days of life for breaking poverty cycles and building lifelong potential. This policy ensures quality early life learning reaches more children.

Children in Kenya cannot join formal pre-primary classes before age four

Dr Consolata Mutisya, Machakos County Executive (CECM) for Education, says the county has established daycares within sub-counties at Ksh50 per day as “running costs are met by the county government in partnership with the Melinda Gates Foundation and the University of Nairobi, which provides food and pays for the utilities.”

The county provides food to public ECDs, increasing enrollment from 37,000 to 47,000 children within a year.

While today children require birth certificates as they cannot join formal pre-primary classes before age four, Dr Mutisya says that was hardly the case in her time.

Back then, she says, children started school based on a simple test of touching the ear. But tall children often got enrolled too early, “yet they were not fully developed and ready to join school.”

Kenya shifted from the 8-4-4 system of education to CBC, which promotes play-based, child-centred learning, focusing on skills and talents over academics alone.

Research from the Ministry of Education on Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC), shows Early Childhood Development Education (ECDE) is improving but still faces challenges. While policies and curriculum have advanced, gaps remain in inadequate funding, wanting facilities, inconsistent teacher training and low pay for ECDE teachers.

Unlike Kenya, teachers in early childhood education in Finland must have a university degree

Early learning systems differ worldwide, shaped by culture, economy, and policy. In Africa, South Africa has a strong national Early Childhood Development (ECD) policy, and though like Kenya it faces challenges in providing equal access and quality, especially in underserved areas, South Africa has centralised all ECD responsibilities under a national body for a more coordinated approach, unlike Kenya, which manages ECD through county-level systems.

In Europe, Finland’s early childhood education (ECE) model is known for its focus on play and discovery. Unlike Kenya, teachers must have a university degree. Early learning is treated as a universal right, with municipalities required to provide services.

Fees are based on family income, often very low or waived for low-income families. The system is well funded through both state and municipal support.

In Asia, Japan’s ECE lays heavy emphasis on group-oriented activities, discipline, and moral education alongside play-based learning. While not compulsory, almost all children attend a kindergarten or nursery, according to EdDesign Magazine and research on the Japanese ECE system.

Kindergartens are run by the Ministry of Education, while nurseries fall under the Ministry of Health, focusing on independence, social skills, and respect for others. The curriculum first builds character and basic habits like cleaning up, before moving to formal academics.

This article was first published by Willow Health Media on August 31, 2025.