Sickle cell disease in western Kenya is frequently misdiagnosed as malaria or pneumonia, leading to repeated treatments and delayed care.

When a paediatrician finally took Selina Olwanda Ogweno’s call, the first question she asked was not about medicine or hospital visits.

“I asked him, ‘Will I be able to see my grandchildren?’” she recalls. “I remember he laughed very loudly and said, ‘Yeah, why not?’”

That moment, she says, marked the beginning of her journey from fear to understanding sickle cell disease, a genetic blood disorder that affects families in Kenya but is still widely misunderstood.

Her son was diagnosed with sickle cell disease at just nine months old, after repeated hospital admissions for vomiting, diarrhoea, anaemia and unexplained weakness.

“When the doctor casually said, ‘Oh, he has sickle cell,’ I almost dropped,” she says. “I remember holding my baby and just crying. Nothing else she said made sense after that.”

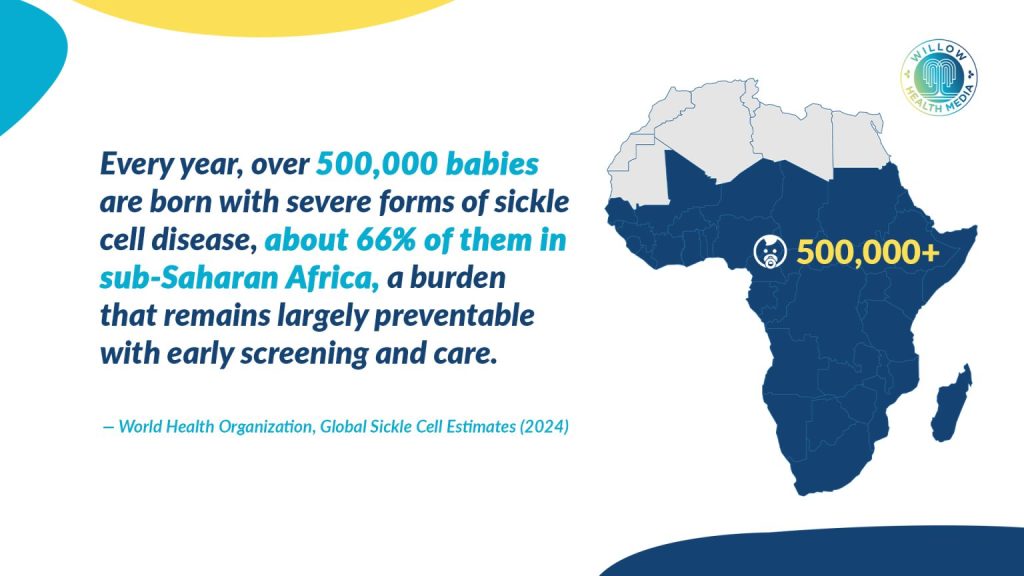

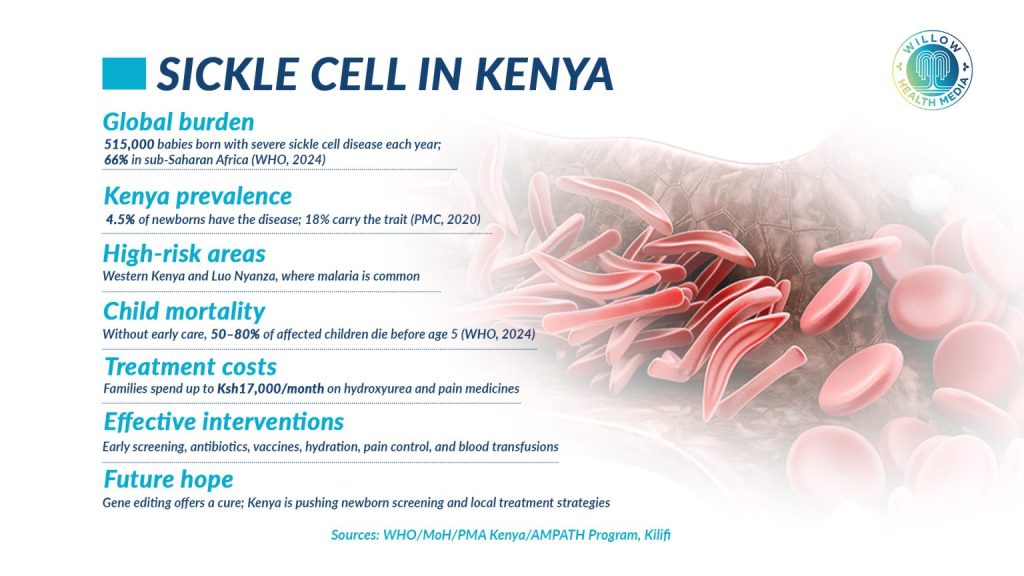

A disease is often missed until it is severe. Sickle cell disease is inherited when a child receives two abnormal haemoglobin genes, one from each parent. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), more than 500,000 babies are born with sickle cell disease globally every year, with the highest burden in sub–Saharan Africa. In Kenya, the disease is most prevalent in malaria-endemic regions, particularly parts of western Kenya.

Pain occurs when sickled red blood cells block blood vessels, even grown men and women cry

Early symptoms often appear in infancy and include persistent anaemia, jaundice, swelling of hands and feet and episodes of severe pain.

“One minute the child is playing, the next minute they are in extreme pain,” Selina explains. “The hands or feet are swollen, and the child cannot even stand.”

Pain occurs when sickled red blood cells block blood vessels, reducing oxygen flow and causing intense inflammation. These episodes can be so severe that, as she puts it, “even grown men and women cry”.

Yet diagnosis is often delayed.

“Many children are treated for malaria, pneumonia or diarrhoea again and again,” she says. “Sickle cell is never identified as the underlying cause until complications happen.”

Those complications can include stroke, severe infections, organ damage and early death if care is not started early.

Her first encounter with sickle cell had come years earlier, when her nephew was diagnosed in 1999.

“Our reaction was just, ‘Oh, okay,’” she admits. “Today I feel bad, because we did not understand what he was going through. Nobody explained to us what sickle cell was.”

By the time her own child was diagnosed, the shock was deeper, but so was her determination.

“My husband and I decided that whether he was sick or not, we would go for clinic reviews every month,” she says.

Selina works to establish subsidised clinics, reduce stigma and misinformation around sickle cell

She also found support through the Children’s Sickle Cell Foundation, where she met other parents and adults living with the disease.

“There was a man in his 30s at one meeting,” she remembers. “I knew him professionally, but never knew he had sickle cell. When he said, ‘Yes, I do,’ it gave me so much hope.”

At the time, she says, people around her were constantly talking about age limits.

“They would say, ‘When the child reaches this age, they will die.’ But seeing an adult living with sickle cell changed everything.”

Selina is a Kenyan sickle cell advocate and leader whose work has shaped the support landscape for affected families in the country.

As the Chief Executive Officer of the Children’s Sickle Cell Foundation, Ogweno has turned her personal experience as a mother of a young adult living with sickle cell into national activism, aiming to improve access to care, education and policy engagement for sickle cell patients and caregivers.

She works to establish subsidised clinics in high-burden areas, educate healthcare providers and communities on proper disease management, and reduce stigma and misinformation that surround sickle cell disease in Kenya.

Sickle cell follows basic genetic rules taught in secondary school biology, but is rarely discussed in real life

“Many parents… don’t know where to turn for help or how to manage the condition. I wanted to change that,” she says, underlining the importance of early diagnosis, informed choice and dignity in care.

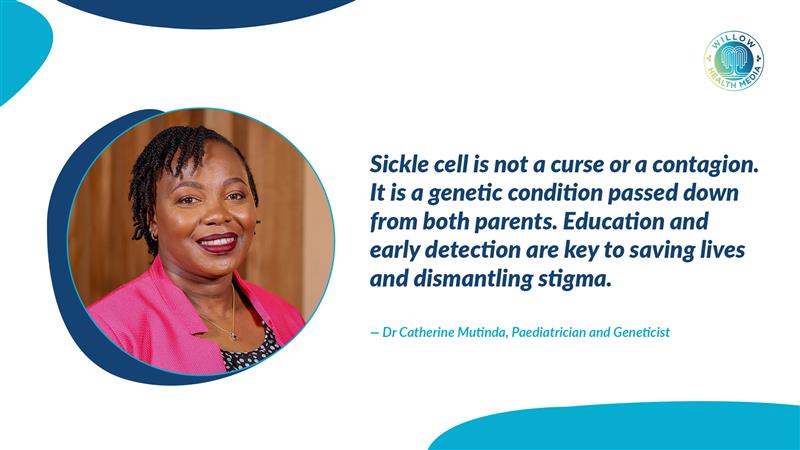

Sickle cell disease follows basic genetic rules taught in secondary school biology, but rarely discussed openly in real life. A child can only have the disease if both parents carry the sickle cell gene.

“I wish I paid attention in biology,” she says. “I only woke up after my child was born.”

She later discovered a history of sickle cell on her father’s side of the family, including children who had died young, likely undiagnosed.

“That lack of information led us down a very dark path without knowing what our family tree looked like,” she says.

She now strongly advocates for genetic testing and counselling before marriage or childbearing.

“It is not about blaming anyone,” she explains. “It is about giving people information so they can make informed choices.”

Deciding to have another child was one of the hardest choices she and her husband faced.

“I was terrified,” she says. “I prayed and negotiated with God.”

They waited more than five years before trying again. This time, armed with knowledge, she requested early testing.

My firstborn knows why he takes medicine every day, my second understands why his brother does

“When we saw a normal gene in the results, I just said, ‘Thank you, God,’” she recalls.

Her second child turned out to be a carrier, not affected by the disease.

Today, both her children understand sickle cell.

“My firstborn knows why he takes medicine every day. My second understands why his brother does,” she says. “We talk about it openly.”

Kenya has recently begun implementing newborn screening for sickle cell in selected regions, including parts of Kisumu County. Early screening allows children to be linked to care before complications occur.

But she warns that screening alone is not enough.

“Where do these children go after diagnosis?” she asks. “Do we have facilities, medicine and trained healthcare workers close to their homes?”

She points to successful clinic models run in partnership with private facilities and county governments, offering subsidised care and education.

“When care is holistic, families gain confidence,” she says.

With information, care and community, sickle cell does not have to steal the future

Beyond clinics, the Children’s Sickle Cell Foundation, where Selina is the CEO, uses community outreach, sports events, school programmes and training for healthcare workers to change perceptions.

“Some people think sickle cell is contagious or a curse,” she says. “That stigma hurts children more than the disease itself.”

Her hope is simple but powerful.

“I want a future where people can talk about sickle cell without pointing fingers,” she says. “Nobody chooses how they are born.”

And when she thinks of the question she once asked in fear, her answer now is steady.

“My grandchildren are people I look forward to meeting,” she says. “With information, care and community, sickle cell does not have to steal the future.”