Siaya County’s success shows that awareness and access save lives, yet stigma, poverty, and myths still block free healthcare for some in Kiambu County

Mary Wanjiku Kamau, mother of a three-month-old, cradles her baby as she recalls almost missing her child’s first immunisation schedule.

“I didn’t know the vaccines were free,” she says softly. “I thought they would ask me for money, but I didn’t have any money that day.”

Wanjiku, like many other residents in Mwimuto, is a casual labourer who earns a daily wage from menial jobs. But with the birth of her baby and the constant demands of motherhood, work took a back seat, and finances became tight.

The financial constraints would not have been a hindrance to Wanjiku’s baby getting her vaccines on time, but without information on the availability of free vaccines at the nearby Level 4 Wangige Hospital, she risked her baby’s health to vaccine-preventable diseases.

Thankfully, a Community Health Promoter (CHP) visited her home and assured her there would be no charges, enabling the baby to get immunised for free.

Wanjiku’s near-miss illustrates a broader problem in Wangige, a small, sleepy town some 15 kilometres north-west of Nairobi, where residents are missing out on free critical healthcare services due to poverty, misinformation, infrastructure gaps, and deep-seated socio-economic barriers.

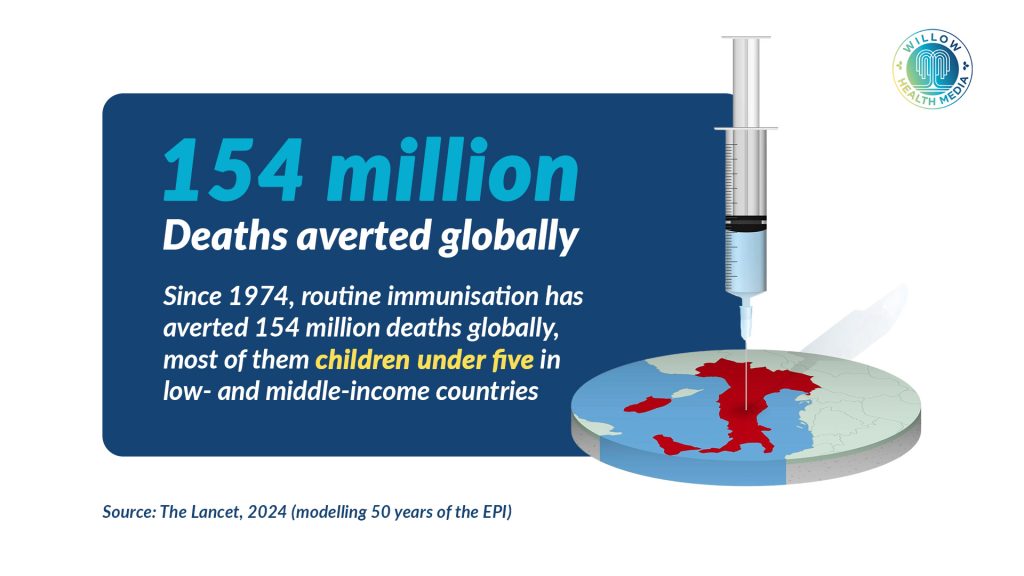

Vaccination is one of the most effective tools in public health, with the World Health Organization (WHO) estimating that immunisation prevents between 3.5 and 5 million deaths globally each year, most of them among young children.

Since 1974, the Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) has saved an estimated 154 million lives, including 146 million children under five years old. In fact, routine immunisation against diseases such as diphtheria, measles, rotavirus, and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) accounted for approximately 86.9 million fewer deaths in children under five between 1990 and 2019, a reduction of roughly 24 per cent in child mortality.

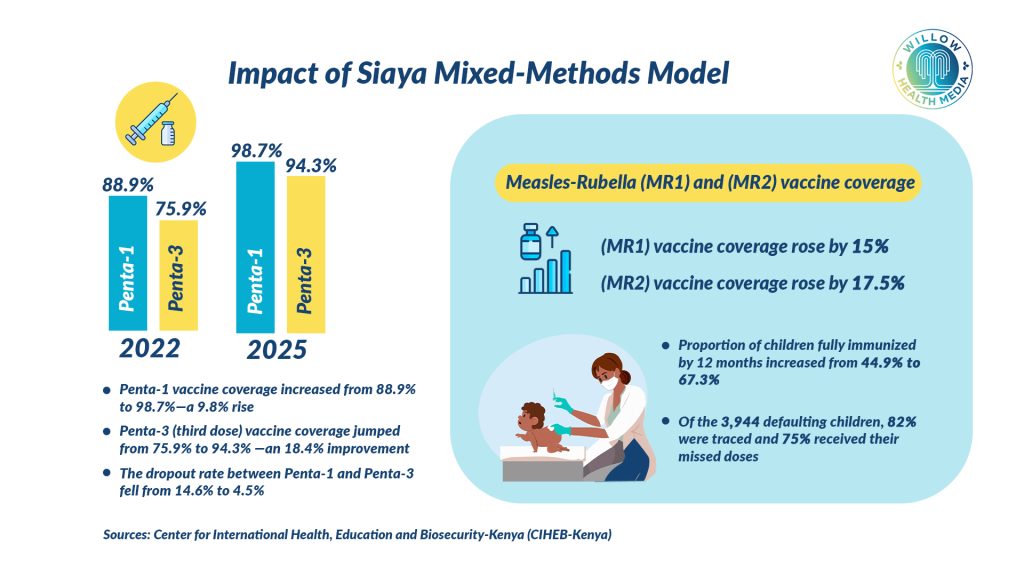

Closer home, evidence shows that catch-up vaccination strategies yielded remarkable results. In Siaya County, a mixed-methods initiative that integrated catch-up vaccination strategies into routine immunisation services yielded remarkable results.

These gains were driven by a combination of interventions, including routine screening in health facilities to check immunisation status during any visit; defaulter tracing, whereby CHPs actively identified children who missed vaccines; and community awareness efforts involving local leaders, caregivers, and CHPs to highlight the importance of timely immunisation.

The Siaya model is proof that when awareness meets accessibility, utilisation of life-saving healthcare services soars.

Like other government healthcare facilities, Wangige Hospital offers free maternal and child health services, HIV and TB screening and treatment, and outpatient services covered under the Social Health Authority’s (SHA) Primary Healthcare Fund.

More than 23 million Kenyans have been registered to SHA, compared to 8 million under NHIF

Every Kenyan has a constitutional right to the highest attainable standard of health, which the government promises to provide through its Universal Health Coverage (UHC) plan.

Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi, while announcing the 2025/26 budget in June, said the government has expanded Social Health Insurance to enhance the attainment of UHC, and “as of May 2025, more than 23 million Kenyans were registered to SHA, representing a remarkable 175 per cent increase in membership compared to the eight million previously enrolled under the defunct NHIF.”

But walk through the dusty villages in Wangige and the story is similar: many people do not know that these services, including registration to public health insurance, are free.

Anne Mwingi, the CHP who helped Wanjiku get immunisation for her baby, says rampant myths and misconceptions are a barrier to health-seeking behaviour. Some damaging myths are that Antiretroviral (ARV) treatments for HIV cause infertility, or that vaccines weaken children.

“People ask me if the hospital will charge them, even for something like a baby’s injection”

Mwingi walks door-to-door with a small folder of leaflets. Some are worn and out of date, but they still carry important information.

“People ask me if the hospital will charge them, even for something like a baby’s injection,” she says. “We need better materials in local languages. Many residents here speak the native Gikuyu first, then Kiswahili. Posters in English don’t help much.”

The 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census and subsequent county fact sheets indicate an adult literacy rate of about 88.5 per cent in Kiambu County where Wangige sits, reflecting relatively high education levels compared to the national average.

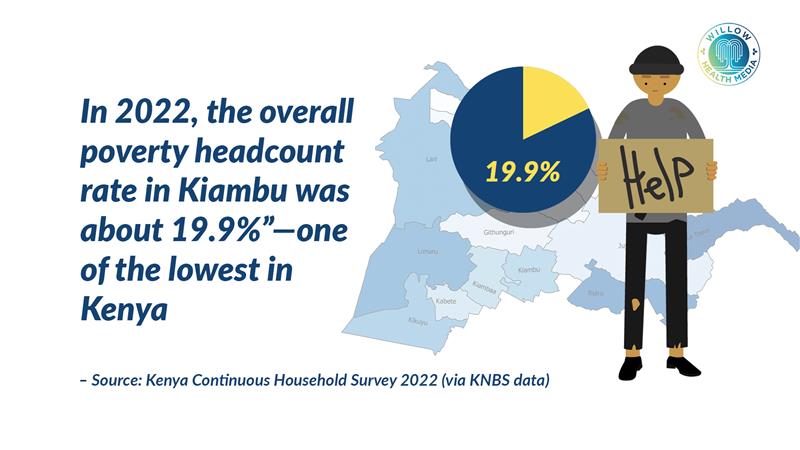

However, data from the Kenya Continuous Household Survey 2022 shows that roughly 19.9 per cent of households in Kiambu live below the poverty line, with many residents relying on informal work such as small-scale trade, casual labour, and boda boda (motorcycle taxi) services.

Poverty, combined with the perception that healthcare services require payment, discourages some residents from seeking timely medical attention, even when free services are available at public facilities.

Due to low awareness and misinformation, many residents opt for private clinics that charge consultation fees but offer quick service, pharmacies where they self-medicate without diagnosis, traditional healers for herbal remedies, or waiting until illness worsens, sometimes reaching the hospital only when critically ill.

The consequences of stigma, disinformation and misinformation are severe

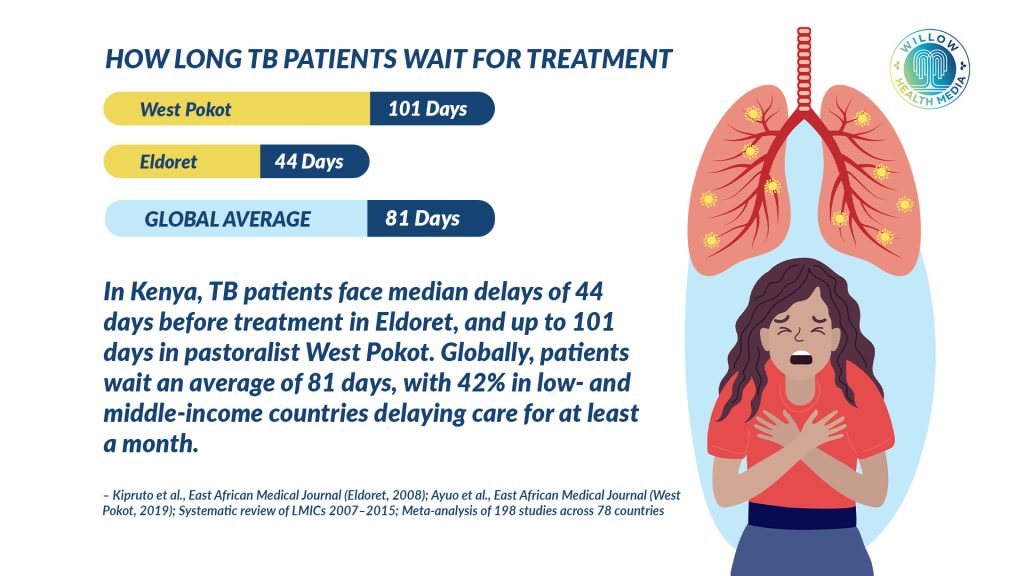

James Njoroge, also a resident of Mwimuto and recently diagnosed with Tuberculosis (TB), admits he delayed in seeking help, but his was a case of misinformation and stigma.

“I thought treatment would be expensive, and I was afraid people would judge me,” he says. But a clinical officer explained that TB treatment is free, and that gave me courage.”

Stigma remains a powerful barrier in close-knit communities, where rumours spread quickly, and illnesses like TB and HIV still carry shame.

According to Wangige Hospital records, over 20 per cent of patients admitted for TB in 2024 had delayed treatment by more than three months, increasing community transmission risk.

The consequences of stigma, disinformation and misinformation are severe. According to WHO, they lead to higher TB and HIV transmission from delayed diagnosis and treatment, sporadic outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, increased mortality from treatable conditions such as pneumonia or diarrhoea in children, and higher healthcare costs in the long run for both patients and the public system.

According to Mwingi, CHPs need support with training, updated resources, and transport allowances to expand coverage.

Residents call for medical outreaches in local dialects including Gikuyu and Swahili

She says she often uses her own money for transport to reach remote homes, and “If we had more support, training, updated leaflets, even airtime to call people, we would reach more households.”

Residents also call for medical outreaches in local dialects, including Gikuyu and Swahili, to break the communication barrier. They further recommend using respected community members and recovered patients to share real stories as a way to reduce stigma, especially for HIV and TB.

Outreaches done through free medical camps and digital campaigns on social media networks will help address misinformation, as will school-based awareness by integrating health rights education into school curricula.

Already, Kiambu County has made major strides in upgrading its healthcare network. Community health workers are regularly trained and mobilised for various health initiatives, including a recent training program focused on Community TB Care (CTBC), which involved over 50 Community Health Assistants (CHAs) and CHPs, equipping them to identify TB symptoms and support patients.

Despite this, CHP-to-household ratios remain below the Ministry of Health target, meaning many homes do not receive adequate outreach in a year.

“Access to healthcare services in public facilities is more than a policy problem in Kiambu County,” says Mwingi. “This is not just a healthcare issue, it’s about communication, trust, and dignity.”

For Kenya to successfully achieve UHC, people need to know and trust what the plan offers and how it can benefit them equitably.

The writer was a student at KEMRI Graduate School Health Journalism & Public Health Communication Course. The story is a collaboration of KEMRI Graduate School, University of Liverpool and Willow Health Media.

This story was first published by Willow Health Media on August 18, 2025.