We have enough HIV drugs in the country “to last months” says Dr Ruth Laibon-Masha, head of National Syndemic Diseases Control Council

On a Friday afternoon in the Soweto area of Nairobi’s Kibera slum, Vincent Omondi sits on his bed staring blankly at the red-earth wall of his single-roomed house. His wife is seated next to him, silent, folding laundry on the table. Golden beams of the afternoon light stream through the ruined gaping walls, striking their faces on their right.

Omondi, his wife and seven out of their eight children are all living with HIV. He is an untrained mason and painter but work, he says, has been hard to come by lately. His youngest child was enrolled in a private school near his house, but he doesn’t have the Ksh3,000 per term school fees. His second youngest was lucky as a well-wisher is paying her school fees.

“I haven’t touched a twenty-shilling coin since I woke up this morning. I haven’t eaten a thing. It is very difficult getting work,” says Omondi whose landlord is threatening eviction over rent arrears.

So, when he heard the news that the US government wouldn’t be funding the programs that enable his family access to HIV drugs, he was devastated.

“So, if these drugs are as unpredictable as we have heard, it has made us fear for our lives,” he says.

Omondi is one among 1.3 million Kenyans living with HIV. At his local Ushirika Medical Clinic, a community-owned hospital, there are 1,200 people living with HIV in the facility’s client records. Many other small facilities dot the sprawling slum serving thousands more. According to the government, all people living with HIV have access to HIV drugs, thanks to funding from donors including the US government, the country’s biggest donor.

But US President Donald Trump’s recent freeze on foreign funding will put the country’s HIV drug inventory in jeopardy and will be worsened by the fact that Kenya is yet to achieve the 15% health financing from the national budget as per the Abuja Declaration of 2001.

This begs the question; how many HIV drugs does the country currently have?

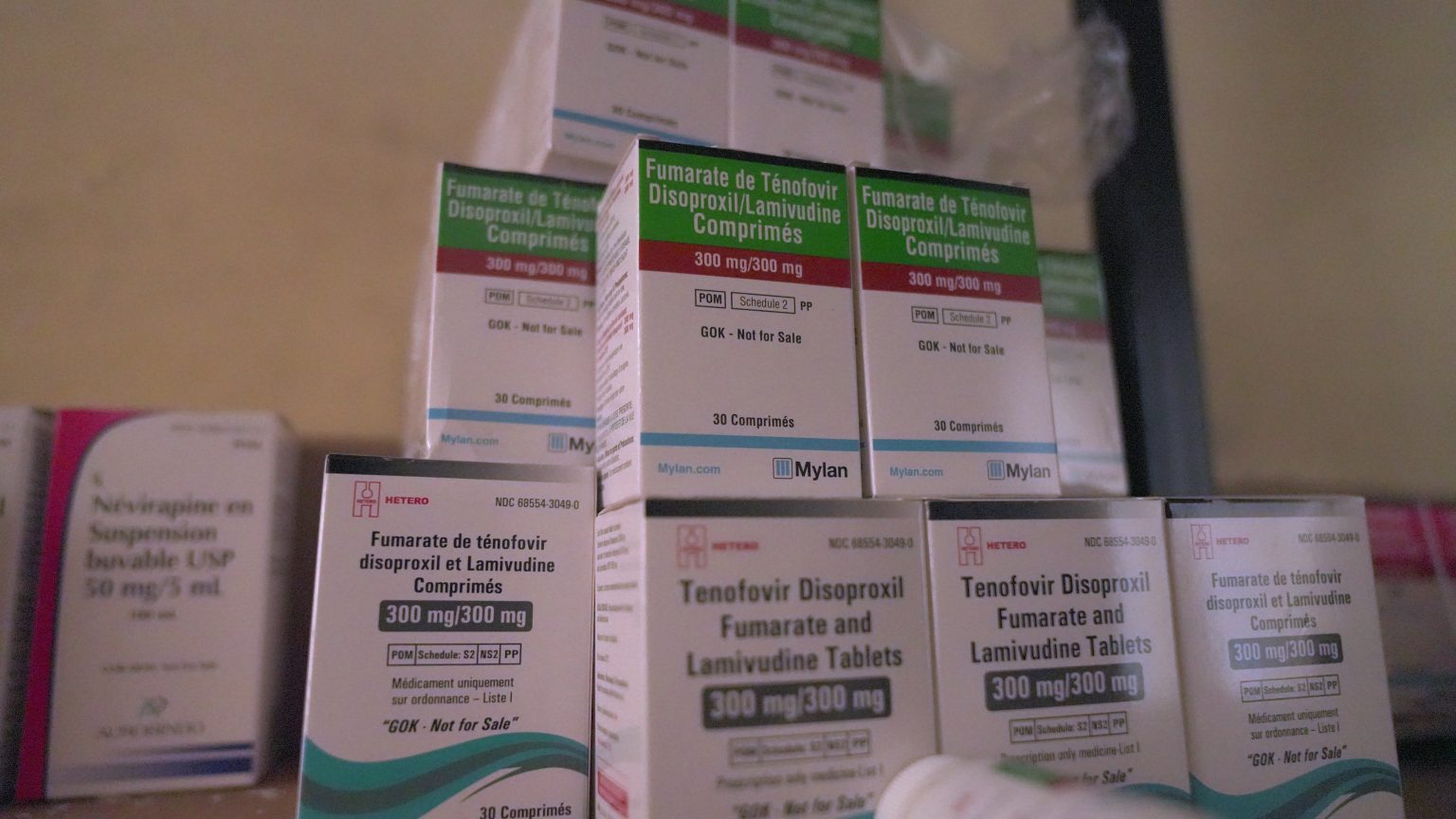

Dr Ruth Laibon-Masha, the head of the National Syndemic Diseases Control Council would rather talk about the HIV drugs supply chain. She told Willow Health that there are enough HIV drugs in the country “to last months”. A quick scan through the online HIV drug inventory – the commodities dashboard – managed by the National AIDS and STIs Control Program (NASCOP), shows that the drugs are available.

However, the different drugs have varying levels of availability in the facilities and in the central stores at the Kenya Medical Supplies Agency (KEMSA).

NASCOP data shows that all 47 counties have over three months of stock of HIV drugs at the facility level. At the central stores, however, some drugs are not in stock while others have up to 38 months’ worth of stock. For instance, TDF/3TC/EFV (tenofovir, lamivudine and efavirenz), a fixed-dose combination of three drugs used to treat HIV/AIDS is not in stock.

In response, Dr Masha said the government cannot stock too many drugs as some have a shorter shelf-life.

“Some of these commodities for HIV management have short expiry period so if for example they are reagents for viral monitoring, you’re not going to just buy them for a year and keep them in their stores,” she said. According to the records, other drugs are pending, meaning they have been acquired and are yet to get to the stores.

Dr Masha explains that the government funding has two other streams for HIV response: the US government through the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and affiliated agencies and funding from the Global Fund for HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria. With the funding, the NSDCC then does “forecasting and quantification” where they stagger purchase of drugs from the three different funds at different times.

“They are a number of items so depending on which items that each funds team was allocated, we stagger them that way so that we manage the supply chain,” she said.

According to the US Department of Health & Human Services, the US government has invested $100 billion (over Ksh12 Trillion) in the global HIV/AIDS response since 2003, an effort it states has saved over 25 million lives, equal to half Kenya’s population. Of this amount, $8 billion (over Ksh1 Trillion) has funded Kenya’s HIV/AIDS response programmes alone in over two decades.

This funding has dominated HIV programming for years, making the government complacent in working towards making HIV programming sustainable and non-dependent on aid. As of 2018, about Ksh86.37 billion was being spent annually in HIV response.

A high percentage- approximately 69% of this was donor-funded, according to a USAID study which recommended that national and county governments should allocate more funding to HIV programs to increase domestic funding.

In 2019, the decline in donor funding put the sustainability of HIV programmes in doubt. An economic modelling study to see the potential of low and middle-income countries to fund their HIV programmes by Lancet found that “low-income countries (such as Haiti, Kenya, Malawi, and Uganda) would be unable to replace even 10% of the funds development assistance contributes towards care and treatment.”

The study foresaw a situation in which Kenya and many developing countries find themselves now with the foreign aid freeze by the US government.

Allan Maleche, the Executive Director of Kelin, an NGO that protects and promotes HIV-related human rights, isn’t surprised that other western countries may follow in President trump’s footsteps to reduce or halt aid for other programmes. “It is possible that there are a few European countries that are inclined to go in that direction as there are more right-wing governments,” he said.

[Photo: Anthony Langat, Willow Health Media]

Kelin Director Maleche is convinced that the government has HIV drugs enough to go for around 15 months. However, if the US government’s 90-day waiver comes to an end and aid remains frozen, he fears for the worst.

“I think it would be a disaster if the US government comes after the 90 days and says they are cutting all their programmes on delivery of HIV services. I think what you’d see is children being born with HIV, people developing resistance and being subject to opportunistic infections which will eventually lead to deaths, and the reversal of the gains that have been made in terms of ensuring over a million people are on treatment and care,” he said.

At Ushirika Medical Clinic, there are HIV drugs only enough for the next three months. Tom Oketch, the administrator of the clinic, does not share Dr Masha’s confidence. While Omondi still has drugs enough to last him for two months, he wishes he could get his hands on a year’s supply for his entire family. “I wish I could get a year’s supply for my wife and children. Life is what I want,” he says.

Ushirika Medical Clinic has however reduced the drugs it issues patients from an initial six months as was always the norm to only one or two months.

“I would want people in government to be a little more realistic and not to chest-thump as if there isn’t going to be anything wrong if this funding is pulled out. I believe and I know that deep inside them they know that it will be a big crisis. I hope that behind their speeches, they are doing something,” said Oketch.

While the short term looks bleak, Dr Masha insists that the government has the situation under control. She said that the government stocks drugs in excess of 12 months in addition to maintaining records of drugs for emergency procurement by government funds if it gets to that.

People living with HIV like Omondi and his family yearn for assurance that all will be well. “So, our plea to the government is to see what they can do so that we do not go without drugs because many people will die.”

In order to have sustainable HIV programmes in the long term, much needs to be done. Maleche said that, for starters, Kenya needs to increase its allocation to health.

“The Abuja Declaration only stated that 15% of the national budget should go towards health. To date, Kenya has never achieved that. But even if that was the case, the Constitution does not limit the national government or the county government to the 15% they are actually able to go above,” he said.

Maleche said that the country needs to prioritize health, ensure a reduction in wastage, leakage and corruption both of donor resources and also taxpayers’ resources, and find public-private-partnerships in the manufacturing of antiretroviral drugs locally. He said that there are a few countries that have managed to fund their own HIV programmes.

“A good example is Botswana, who with this whole stop order issued a statement saying that they had planned adequately to be able to provide ARVs for their citizens,” he said.

The government, on its part, is also working with the private sector to focus more on the manufacturing of HIV drugs.

“We are lucky as a country to have a supplier who does local manufacturing for one drug that is critical for us. Having a local manufacturer reduces our lead time and it ensures that we can now purchase in portions, and we don’t have to worry about the shipment time,” she said.