The 2023 Auditor General’s Report also reveal that NHIF paid 10, 000 normal deliveries on one patient!

The now-defunct National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) was a house of scandal, if the damning report for 2023 from the Auditor General, Nancy Gathungu, is any yardstick.

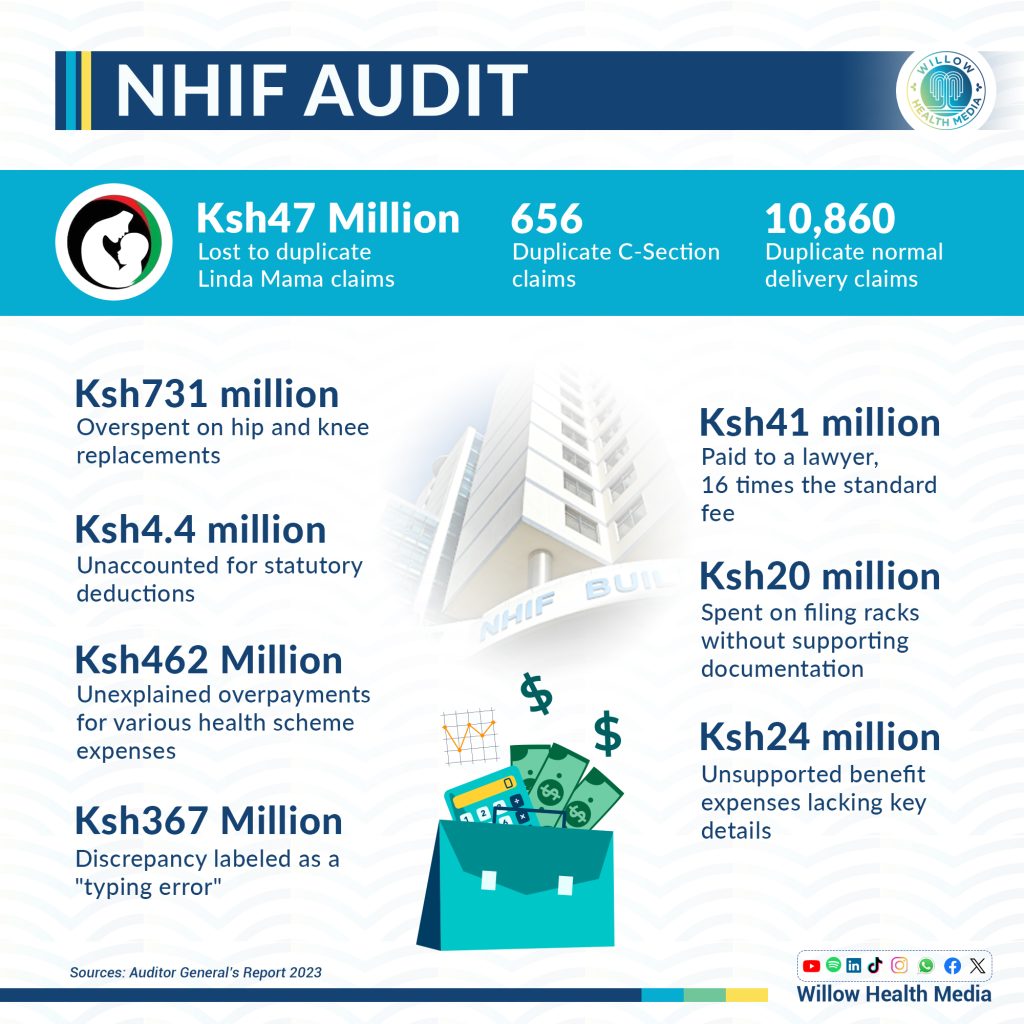

Picture this: One patient had over 656 caesarean-section deliveries, while 10,860 normal deliveries were carried out on another patient.

Hip and knee replacement surgeries were over costed by over Ksh731 million while over Ksh20 million was blown on invisible filing racks.

The Auditor General’s Report paints NHIF as a scheme for profiteers through unchecked fraud, suspicious overpayments and inexplicable expenses: There were Ksh24 billion spent on ‘Unsupported Benefit Expenses’ from various schemes, but which “lacked details of member numbers, identification numbers, hospital names, employer codes and in some instances the claim amounts contained negative values,” notes the Auditor General.

Further, she reveals that the administration expenses balance of Ksh673 million for various enhanced schemes “lacked details on the actual activities carried out, items procured, number of parties receiving services and payee details.”

NHIF had 878,104 indigent members sponsored by the government at Ksh6000 each translating to Ksh5.2 billion.

However, NHIF indicated it had one million indigent members translating to a budget of Ksh6 billion. The over 120, 000 extra ghost beneficiaries ‘spent’ Ksh730 million!

The scandalous run of NHIF ended on October 1, 2024, when the Social Health Authority (SHA) took over under Dr Abdi Mohamed as chairperson who said SHA has safety nets designed to end the freewheeling graft that was the staple prescription at NHIF.

Ksh4.4 billion of statutory deductions unaccounted for

One glaring anomaly lies in the Ksh4.4 billion which NHIF collected as statutory contributions from five schemes but failed to provide supporting documentation for this colossal sum. Essential details like dates of receipts, E-slip reference numbers and customer codes, were absent, with schedules displaying only block figures.

Even more troubling, there was no monthly breakdown showing each member’s individual contributions, which makes confirming the accuracy of the deductions nearly impossible.

Ksh462 million in unexplained overpayments for health scheme expenses

Another major finding revealed an unexplained overpayment of Ksh462 million for various medical services under NHIF. Against an expected expenditure cap of Ksh502 million, the actual expenses ballooned to Ksh34 billion.

Individual categories show severe discrepancies: The cost limit for normal deliveries was Ksh370,000, yet NHIF disbursed Ksh1.7 million—an excess of Ksh1.3 million. Similarly, caesarean-sections that should have cost Ksh930,000 ended up totalling Ksh2.2 million, creating an overpayment of Ksh1.3 million.

Rehabilitation services were similarly mismanaged, with expenses reaching Ksh4.6 million against a limit of Ksh1.3 million—an overpayment of Ksh3.3 million. Even minor surgeries saw costs exceeding their limit by Ksh29 million.

For major surgeries, NHIF paid out Ksh687 million surpassing the set cap of Ksh402 million resulting in a difference of Ksh28 million. Specialized surgeries, basic and complex chemotherapy, MRI, and CT scans all displayed similar inflated figures. For example, CT scans alone showed an overpayment of Ksh95 million, with Ksh115 million paid against a limit of Ksh20 million.

Ksh47 million spent on duplicate “Linda Mama” deliveries

A separate audit into the Linda Mama Programme—an initiative aimed at providing maternity care for mothers—uncovered Ksh47 million lost to duplicate payments.

Within this program’s total expenditure of Ksh4 billion, NHIF issued payments for 656 duplicate case codes associated with caesarean sections, amounting to Ksh5.7 million. Each duplicated payment was billed to the same patient, suggesting gross oversight or fraud in the billing process.

Similarly, Ksh41 million was paid for normal deliveries under 10,860 duplicate case codes, again billed for the same individuals.

Costly “typing error” amounting to Ksh367 million

The Auditor General further exposed a Ksh368 million discrepancy between hospital-billed amounts and actual claims paid by NHIF.

While the statement of profit and loss reflected total benefit expenses of Ksh71 billion, the billing records indicated hospitals charged Ksh447 million, against which NHIF paid Ksh815 million, creating a substantial unexplained variance.

Across various schemes, the discrepancies painted a concerning picture.

For instance, under the National Health Scheme (NHS), NHIF disbursed Ksh487 million, whereas hospitals only billed Ksh281 million, yielding a Ksh206 million variance. In the Edu Afya Scheme, hospitals billed Ksh24 million, but NHIF paid Ksh49 million or Ksh24 million more.

Each scheme, including the Civil Servant and NPS/KPS Schemes, displayed such variances, and when questioned, NHIF management attributed these discrepancies to simple “typing errors” made during data entry into the E-claim system.

While plausible, the explanation fails to address why reconciliation processes did not flag such massive errors, nor was there any evidence of requests for refunds to correct these overpayments.

Ksh41 million paid to a lawyer—16 times the standard fee

Another red flag involves Ksh41 million paid to a law firm for representing NHIF, despite the advocate’s remuneration order suggesting a payment of only Ksh2.5 million. That was an excess of Ksh39 million—over 16 times the standard rate.

Ksh20 million for filing racks with missing documentation

Concerns also emerged over NHIF’s Ksh20 million expenditure on filing racks with essential procurement documentation missing. The Auditor General’s report noted the absence of Local Purchase Orders (LPOs), invoices, delivery notes, and committee minutes necessary to validate the purchase.

The lack of an S13 counter receipt voucher and an S11 counter requisition and issue voucher further heightened concerns over compromised transparency and accountability in the procurement process.

How SHA will eliminate ‘ghost members’

The newly established Social Health Authority (SHA) has assumed NHIF’s responsibilities and is tasked with restoring transparency, accountability and governance. SHA management now faces a critical mandate to prepare accurate financial statements in line with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and to institute robust internal controls to mitigate against financial misstatements, whether by default or design.

In accordance with the Public Audit Act 2015, SHA is required to submit financial statements to the Auditor-General in compliance with all relevant laws and regulations- with the SHA Board of Directors playing an oversight role.

According to SHA chair, Dr Abdi Muhammed, the authority has instituted several key strategies to curb fraud including the introduction of biometric identification, including fingerprinting. This ensures only legitimate patients are registered thus helping prevent impersonation and eliminate ‘ghost’ members.

Dr Muhammed further explained that SHA will use a “single source of truth” mostly data from the Registrar of Persons which will link each patient’s ID to their health records. This will effectively enable the tracking and monitoring of healthcare services provided therefore reducing likelihood of fraudulent claims.

Additionally, SHA has strict verification processes for health facilities, doctors, and other medical professionals to undergo thorough registration checks before being included in the system. This ensures that only accredited and legitimate service providers can offer care under the SHA program.

This way, Dr Muhammed believes, SHA will create a more transparent and accountable healthcare system, minimizing fraud and misuse of resources as “only five per cent of contributions will go into administering the Fund unlike the case before where up to 30 per cent went into the function,” he told Willow Health.