Remember Bruce John Khajira? In September 2024, this Mombasa blogger was abducted from his home, sexually assaulted, and the incident recorded and circulated online.

One night in 2022, Alfred Buya woke to loud noises outside his Bamburi home. When he stepped out to investigate, he had no idea armed attackers were waiting in the shadows, baying for his blood. The enraged mob rained blows and kicks on him, others dragged him on the stony ground. His crime? Identifying as homosexual and advocating for the rights of victims of sexual violence.

“They grabbed my hand and ripped out flesh. They hit my head and back and dragged me for almost five kilometres, insulting and assaulting me,” recalls Buya.

Beaten and bleeding from the torment lasting more than three hours, Buya eventually stumbled into a police station. But he could not stand up to record a statement. Fearing he had sustained serious internal injuries, the cops sent him to a hospital.

Buya was admitted and received specialised treatment for three days, but was mobbed twice after returning home in 2023 and 2024. He sustained physical injuries and psychological scars. Though he moved houses in between burglaries, the trauma lingers on in panic attacks.

Buya in among thousands of men living under the dark shadow of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in Kenya.

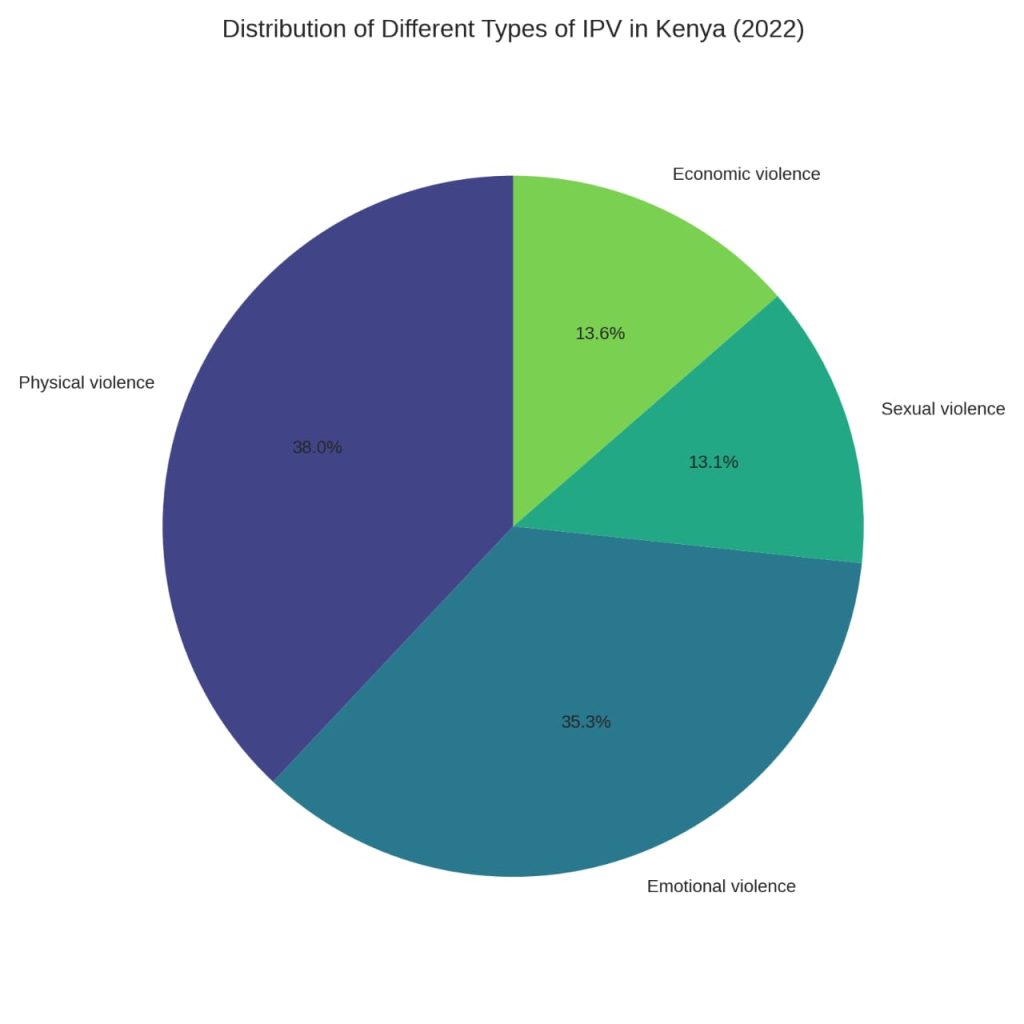

The 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) indicates that the overall prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is around 41 per cent, with partner violence at 30 per cent physical, 28 per cent emotional, 10 per cent sexual, and 11 per cent economic abuse.

Southwest counties and parts of Central Kenya experience more physical abuse, with emotional violence the most common form of violence experienced by men, followed by economic and sexual violence. But men in coastal regions of Kenya could be experiencing traumatic suffering that needs attention.

Such incidents go unreported,d resulting in trauma, shame, fear, stigma, difficulty finding psycho-socio support, isolation and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Remember Bruce John Khajira? In September 2024, this Mombasa-based blogger was abducted from his home in Bamburi and subjected to sexual assault, which was recorded on video and circulated online, sparking widespread outrage. Four suspects were arrested and charged with offenses including abduction, gang rape, and assault with intent to cause actual bodily harm.

Khajira had been critical of the county government, whose officials were summoned by the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI).

But such incidents go unreported, resulting in trauma, shame, fear, stigma, difficulty finding psycho-socio support, isolation and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Zaib Wanga, a PharmTech and SGBV community champion, says men bottle up and tolerate suffering as nursing hardship is society’s idea of a ‘complete man’, yet “they should speak up and inform authorities if they experience violence.”

Wanga laments that “By the time most speak out, it is too late, and depression has fully taken over. Some end up dying by suicide.”

Then there is Brian* from Kisauni in Mombasa County. He has been married for five years and has two children. But his life mirrors a horror film as his wife “brings men into the house and sometimes forces me to get intimate with them and beats me if I refuse,” says 30-year-old Brian. “She also gets intimate with them in my presence.”

The humiliation leaves him feeling “very bad and demoralised”, but he stays in the abusive marriage “to maintain peace, and when I see my children, I am filled with hope.”

Brian is a tout and earns less than his 38- year-old wife who makes more money running a hair salon. The income disparities also see her scolding him in front of the children and neighbours. Though he pays rent and contributes to household bills, he often seeks accommodation elsewhere and only stays in the marriage because “I won’t be granted custody of the children. I fear they will be mistreated and want them to enjoy my presence in their lives.”

Most male victims of sexual and gender-based violence fear seeking help due to stigma, as no one will believe that a man can be sexually abused

A 2019 World Bank report showed that men experience significant interpersonal violence, often perpetrated by teachers, parents, and other men.

The 2019 Kenya Gender Based Violence Service Gap Analysis showed that 44 per cent of men (15-49) face physical violence in their lifetime, 12 per cent in the past year. Sexual violence affects six per cent of men, with two per cent experiencing it in the past year.

Jamila Hassan is a child protection volunteer and gender champion at the Directorate of Children’s Services in Mombasa County. She argues that most male victims of sexual and gender-based violence, fear seeking help due to stigma as “No one will believe that a man can be sexually abused, yet they can be gang raped or even sodomized.”

She says men hardly open up due to the stigma that starts at the police stations when filing complaints. Fearing being branded as wimps, they prefer reporting to case workers like herself, besides seeking help anonymously. “I help survivors access hospitals, the police, and courts. I ensure the case is heard and justice is sought, but men don’t like reporting, making it very hard.”

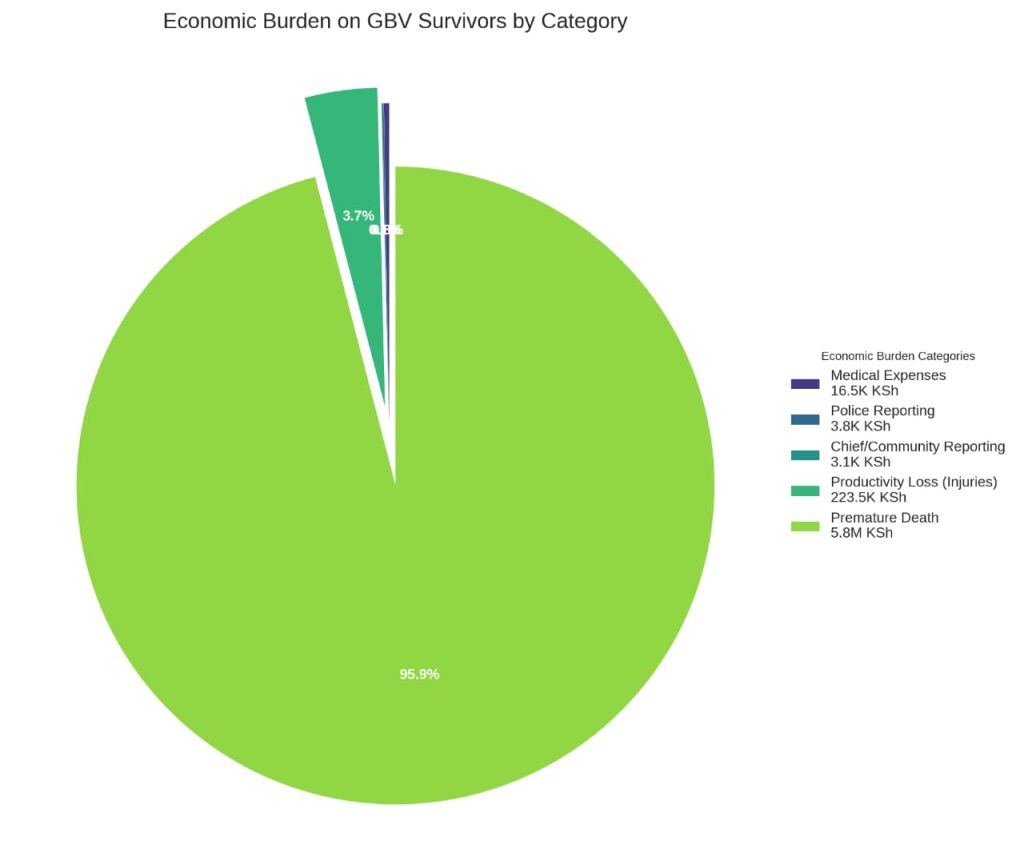

To make matters worse, such violence takes a silent financial toll, according to a 2016 report by the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC).

On average, medical-related expenses take up most of the cost at Ksh16,500, followed by reporting the incident to police at Ksh3,800, while the area chief and community structures consume over Ksh3,000 for a survivor of gender-based violence.

The Economic Burden on Survivors 2016 further estimates the cost of loss of productivity from serious injuries and premature death at over Ksh220,000 and Ksh5.8 million, respectively.

In Buya’s case, even after filling a hospital P3 form and reporting to the police, the perpetrators have never been arrested, having fled to neighbouring Uganda.

Despite the inclusion of gender desks in police stations since 2004, the lack of resources, including training budget, equipment and staffing, hampers their functionality

Henix Obuchunju, a health and SGBV activist, notes that “society has empowered women more and forgotten the boy child” and despite rising cases, there’s usually insufficient data on men and gender-based violence and without statistics, it is difficult to provide solutions to address the problem.”

The Mombasa County Gender-Based Violence Technical Working Group, for instance, launched a toll-free telephone number and SMS line for residents to report cases of gender-based violence during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, but Jamila says, “We receive about 200 calls every week… but most are from women. Men do not make calls reporting gender violence; in most cases, the average 100 calls we get in a month from men are to report assaults.”

Jamila adds: “Men fear that people will know their problems, and society will judge them as weak.”

Mombasa County and Nairobi Women’s Hospital have a partnership for free treatment, but few men report to the medical facility.

A report by Amnesty Kenya shows that despite the inclusion of gender desks in police stations since 2004, the lack of resources, including training budget, equipment and staffing, which are crucial to effectively handling cases of gender-based violence in the counties, hampers their functionality.

Efforts to arrest and address sexual and gender-based violence against men are gaining ground, with initiatives like the Women Empowerment and Education for Sexual Health Advocacy (Wezesha) running empowerment programs in Mombasa and Kilifi Counties.

Wezesha Project Officer Susan Lankisa says they have encouraged some men to speak up against violence in collaboration with the Dream Achievers Youth Organization.

Lankisa says Wezesha initially targeted women, but they saw a gap in creating safe spaces for men, training and empowering them, but “we want to ensure that men understand the importance of speaking up as soon as they encounter violence.”

Elijah Rotock, an officer and lawyer at the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR), says some male survivors want access to “legal and mental health support through the criminal justice system”, but they are also trained on ways of “avoiding stigmatisation in the communities and their families.”

KNCHR data reveals that 44 per cent of men aged 15 to 45 years will be affected by sexual violence at least once in their lifetime, and Rotock notes that “There should be safe spaces specifically for men. In workplaces, employers should create platforms such as online spaces, short messages, or discreet apps to report violations.”

Rotock adds that men’s discussions on gender-based violence should also be tailored in social setups like gyms to promote engagement.

Some strategies that so far are working include community advocacy, training male champions to become allies, and using sports tournaments.

Elpina Saha, a Community Health Promoter, believes that the solution to violence against men lies in the hands of women.

Saha has thus mobilized an army of women activists – about 50 young mothers – who have been traversing Maunguja area of Mombasa to “counsel and refer men to relevant authorities” but it’s not easy as most are “not consistent with attending forums, some because of work and others for fear of stigmatization.”

Eunice Lwambi, a midwife and part of the 50 young mothers, says so far, they have equipped more than 100 men with life-saving skills and information on dealing with sexual and gender-based violence.