Kenya is facing a renewed surge in cholera outbreaks in multiple counties, with health facilities struggling to cope with rising admissions. Since January 2025, over 4,000 suspected and confirmed cases have been reported in over 10 counties.

A cholera outbreak in Narok County has killed six people, including an infant, in the last two weeks. The rapid spread has prompted neighbouring counties and national health authorities to increase surveillance and containment efforts.

The first cases were detected after stool samples tested at Trans Mara West Hospital and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Walter Reed Laboratory in Kericho confirmed cholera infections.

By October 6, the outbreak had killed five people in Kilgoris town. This led officials to shut down 20 unhygienic food outlets. Trans Mara West Hospital has been busy, treating at least 44 patients and admitting 18 for specialised cholera care.

Despite intensifying surveillance and treatment efforts, new infections continue, raising questions about sanitation and emergency response lapses.

Narok resident Timguut Junior Laboso criticised the county’s handling of the outbreak, asking, “If there was medicine available in the nearest public facilities, why has the disease continued to claim precious lives?”

Mother of infant who died claimed she bought medication from another patient

The mother of the four-month-old infant who succumbed while on oxygen also complained of a drug shortage, claiming she bought medication from another patient to ensure her baby was treated. The hospital, however, attributed the death to pneumonia with traces of cholera.

Governor Patrick Ntutu confirmed the deaths and said that as of October 6, “five patients have died, 46 patients have been treated, and 32 discharged. We have had one new admission in the last 24 hours, and 50 samples have been taken for testing.”

Ten days later, on October 16, total infections had surpassed 51. The governor said his administration was “doing everything to ensure the places we think are not observing the right hygienic standards will be completely closed.”

Among the victims was Joseph Omwenga, a carpenter aged 60. His wife, Esther, said he developed severe diarrhoea and cramps after eating from local food stalls. “By the time he was admitted, he was severely dehydrated,” she said. “He could not make it despite the doctors’ efforts. We believe he got it from food and river water.”

County health officials suspect the outbreak originated from contaminated rivers and food outlets.

To stop the outbreak, the county closed 50 unsanitary restaurants and a polluted slaughterhouse

“Cholera thrives where hygiene is compromised. Closing these premises will help us cut transmission and protect residents,” said Lucy Kashu, Narok County Public Health Officer.

Kashu confirmed a widespread outbreak in Migingo, Majengo, Kibera, KCC, Olosentu, ACK, Oldonya Oshara, Olalui, Maranatha and Milimani, with mostly responsive patients; locals point to the polluted River Migingo as the cause.

To stop the outbreak, the county closed 50 unsanitary restaurants and a polluted slaughterhouse. Officials are urging residents to boil water, wash their hands, and have banned street food vending.

“We have mobilised and repositioned drugs and non-pharmaceuticals for outbreak response and disseminated cholera prevention messages to all households through community health promoters,” said Dr Samuel Misoi, Trans Mara West Sub-County Hospital Superintendent.

The county is working with the Kenya Red Cross to improve outbreak response, even buying motorbikes for faster reach. The disease is spreading, with neighbouring Kisii reporting over 128 suspected cases, 54 of which are confirmed cholera.

“While no confirmed cholera cases have been reported, we must all work together to keep Kisii County cholera-free,” said Dr Richard Onkware, County Director of Public Health.

Informal settlements with poor sanitation and reliance on water vendors remain particularly vulnerable

In Uasin Gishu, a sanitation inspection earlier this year led to the closure of about 70 eateries. Governor Jonathan Chelilim Bii said, “Prevention is better than managing an outbreak. We will continue random checks to ensure hygiene levels don’t allow such diseases.”

Kenya is facing a renewed surge in cholera cases, with outbreaks reported in multiple counties and health facilities struggling to cope with rising admissions. Since January 2025, more than 4,200 suspected and confirmed cases have been reported in at least 11 counties, according to the Ministry of Health.

A World Health Organization (WHO) – Kenya situation update released on March 12, 2025, confirmed 42 cases, including eight laboratory-confirmed infections and one death, representing a fatality rate of 2.4 per cent.

Turkana County, home to Kakuma and Kalobeyei refugee settlements, had recorded 74 cases by June; 30 of them confirmed, with one fatality.

Nairobi County has also reported cholera cases in Kasarani, Embakasi East, Embakasi Central, Roysambu, Kibra and Dagoretti South. Informal settlements with poor sanitation and reliance on water vendors remain particularly vulnerable. Coastal counties such as Kwale have also reported transmission.

WHO data indicated that Kuria East in Migori County was the hardest hit, with 21 cases and one death, while Kuria West, Suna East and Suna West reported smaller clusters. In Kisumu County, three people died in March after testing positive for cholera, according to Dr Gregory Ganda, County Executive Committee Member for Health.

Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale said in April that the Ministry, in collaboration with counties, had intensified surveillance, contact tracing and health worker training. “We are on high alert in all counties. Surveillance and community awareness have been stepped up, and any alerts are responded to in a timely manner,” he said.

Cholera cases had declined, but resurgence followed recent flooding and lapses in hygiene

The WHO Kenya Office has warned that active transmission continues amid flooding, poor sanitation and fragile infrastructure. Health experts say the current crisis is unusually widespread.

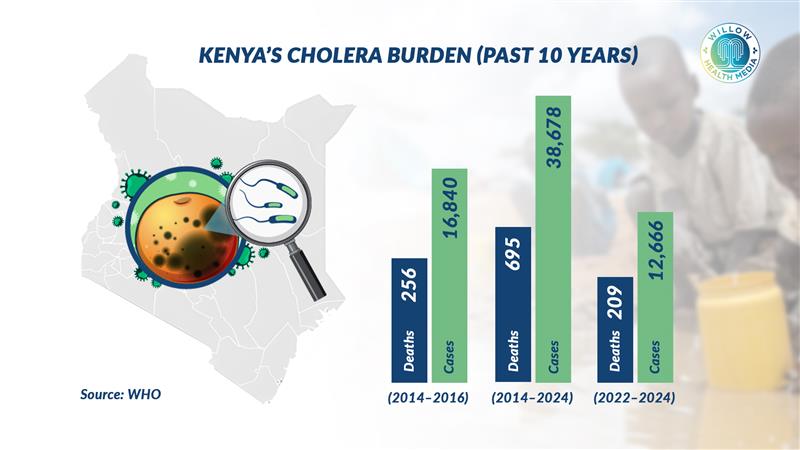

WHO notes that cholera, caused by the Vibrio cholerae bacterium, remains a major public health concern in Kenya. Between January 2022 and December 2024, more than 12,666 cases and 209 deaths were recorded. A 2024 ResearchGate analysis found that Kenya had logged at least 38,678 cases and 695 deaths over the past decade, with the deadliest outbreaks occurring between 2014 and 2016.

Though cholera cases declined between 2017 and 2020 due to improved sanitation and awareness, a resurgence followed recent flooding and lapses in hygiene.

In August 2023, the Ministry of Health launched a major Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV) campaign targeting eight counties after outbreaks that killed 196 people out of 11,181 cases. Over 2.2 million people above one year of age were vaccinated, surpassing the 1.59 million target. However, no subsequent vaccination drives have been conducted since.

A 2024 study in the Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition listed Kenya among 36 countries aiming to eliminate open defecation by 2030 under Sustainable Development Goal 6. It found that seven per cent of Kenyans (about 3.9 million people) still practice open defecation, particularly in low-income areas, increasing cholera risk.

Weak lab capacity and cultural barriers are major challenges

Flooding has also contributed to recent outbreaks, especially in Homa Bay’s Suba South region. A September 2024 review titled Cholera in Kenya: A Scoping Review of Current Research, Evidence Gaps and Future Directions noted that climate shocks such as El Niño and prolonged droughts fuel recurrent outbreaks, especially in urban informal settlements and refugee camps.

The review cited weak laboratory capacity, fragmented reporting systems and cultural barriers as major challenges, and urged full implementation of the National Multisectoral Cholera Elimination Plan (2022–2030), which prioritises water and sanitation improvements, stronger laboratory networks, and community-based health education.

Authorities have called for continued community sensitisation, strict enforcement of hygiene standards, and dissemination of public health information through local health promoters to curb the spread of the disease.