Kenya’s Quality Healthcare and Patient Safety Bill 2025 aims to end preventable deaths, medical negligence, raise the bar on hygiene, staffing, infrastructure and patient care.

Kenya’s government presents the Quality Healthcare and Patient Safety Bill 2025 as a game-changer for the country’s healthcare system. The proposed law aims to boost Universal Health Coverage (UHC), but healthcare workers and observers see it as a power grab that threatens professional independence and could worsen patient care.

The bill’s proponents want to create a safer, more accountable healthcare system. If passed, it would: Force all public and private health facilities to meet strict quality standards, punish poor care with severe penalties – fines up to Ksh50 million and jail terms up to 10 years and create a new central authority to oversee licensing, accreditation, and regulation.

The proposed Quality Healthcare and Patient Safety Authority (QHPSA) would take control of key regulatory roles, including licensing healthcare workers and setting nationwide standards for hygiene, staffing, infrastructure and patient safety.

Supporters argue this addresses long-standing problems that have led to medical negligence, preventable deaths, and poor patient outcomes. Kenya’s healthcare system still struggles with inconsistent service quality, run-down facilities, undertrained staff, and poor oversight in some counties.

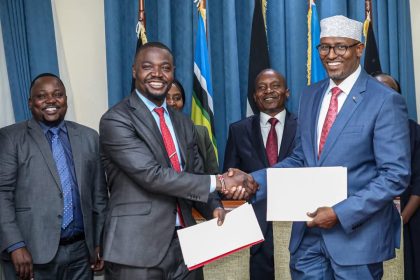

Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale calls this “a major step in transforming Kenya’s health sector” that “reaffirms BETA (Bottom Up Transformation Agenda) priorities and positions Kenya as a continental leader in quality healthcare.”

The bill would also bring emerging fields like medical aesthetics under the same safety rules as traditional healthcare, expanding patient protections.

Healthcare unions, professional councils, and regulatory boards strongly disagree. They argue the reforms are not just unnecessary but harmful.

Peterson Wachira, National Chairman of the Kenya Union of Clinical Officers (KUCO), claims “80 per cent of the bill’s content is already provided for in existing legislation,” including the Health Act of 2017 and the Clinical Officers Act. These laws, he says, already give regulators power to maintain standards, enforce discipline, and protect patients.

Observers point to the Kenya Health Professions Oversight Authority (KHPOA), created under the Health Act, as the right agency to manage healthcare quality. Although KHPOA has never been fully operational, a 2022 High Court ruling by Justice Wesley Korir supported its role and recommended strengthening it. Many argue the solution isn’t new legislation but implementing what already exists.

The proposed Quality Healthcare and Patient Safety Authority (QHPSA) would take control of key regulatory roles, including setting nationwide standards for hygiene, staffing, infrastructure and patient safety. Meanwhile, licencing of doctors, clinical officers and nurses will remain a mandate of the KMPDC, Clinical Officers Council, and Nursing Council respectively.

These bodies aren’t just bureaucracies; they’re professional watchdogs made up of practitioners who understand patient care complexities.

The Kenya National Union of Medical Laboratory Officers (KNUMLO) warned that the bill will “compromise professional independence, patient safety, and the integrity of the country’s healthcare system.” In their statement issued on 17 June, they called the bill “a plot by cartels to hijack the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF)” and described the proposed changes as a backdoor to commercial and political control of healthcare.

In February 2025, this opposition led to the Health Sector Caucus issuing a 14-day nationwide strike ultimatum. Representing nurses, clinical officers, and lab technicians, the group argued that centralizing authority threatened both professionals’ rights and patient safety.

The opposition’s warnings draw on examples from across Africa. In Zambia, Uganda, and South Africa, attempts to merge independent regulatory bodies into centralized authorities led to infighting, funding problems, and reduced accountability.

In Kenya, the Social Health Authority (SHA), which replaced the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF), has already faced difficulties. Delayed claims, underfunding, and governance issues have damaged public trust in the new system. For some, the Bill feels like grand reforms without proper implementation.

Both agree that Kenya needs stronger health standards, better oversight, and safer facilities. But they sharply disagree on how to get there.

For millions of Kenyans relying on public healthcare, the stakes couldn’t be higher. As the bill returns to Parliament, perhaps the most urgent question is whether new legislation is necessary or if political will and full implementation of the existing Health Act 2017 would be enough.