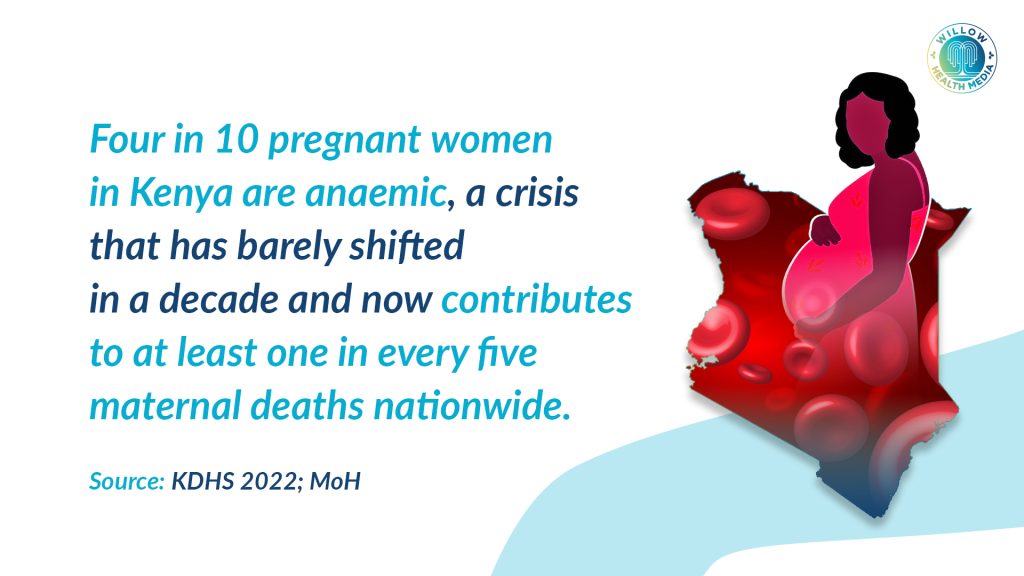

Four out of 10 pregnant women in Kenya are anaemic, with maternal anaemia contributing to at least one in every five deaths, notes the Ministry of Health.

When Linda Kavata discovered she was pregnant in August 2024, she envisioned a joyful journey to motherhood. Within a week, that joy was cut short. “I was struggling to breathe, fatigued, weak, and it started becoming intense,” she recalls.

Alarmed, she went to the hospital, where tests showed her haemoglobin levels were dangerously low for a pregnant woman. She was diagnosed with maternal anaemia, a condition in which the blood lacks enough red cells to carry oxygen effectively.

Linda was prescribed iron supplements and advised to eat iron-rich foods. A month later, nothing had changed. “Even after changing my diet, I was still anaemic.” Her doctor had given her basic dietary advice, but there was no referral to a nutritionist.

Complicating matters further, Linda could not tolerate folic acid because of hyperemesis gravidarum, a severe and persistent nausea and vomiting. Swallowing tablets became impossible. “Constipation, nausea, even the smell is not good,” she says. Today, she calls for alternative supplements in public hospitals and for stronger health education before and after conception.

By her third trimester, her condition had worsened. “My haemoglobin count was seven,” far below safe levels. She began weekly iron infusions at a private hospital, each costing Ksh 10,000, for three weeks. “Without my family’s support, I wouldn’t have afforded them.”

Maternal anaemia is “insufficient blood circulating in the body, making one unable to function properly

The treatment worked. By her eighth month of pregnancy, her haemoglobin had risen to 12. Still, the toll was heavy. “It affected my studies, I couldn’t study for long,” she says, describing the physical, emotional and financial strain.

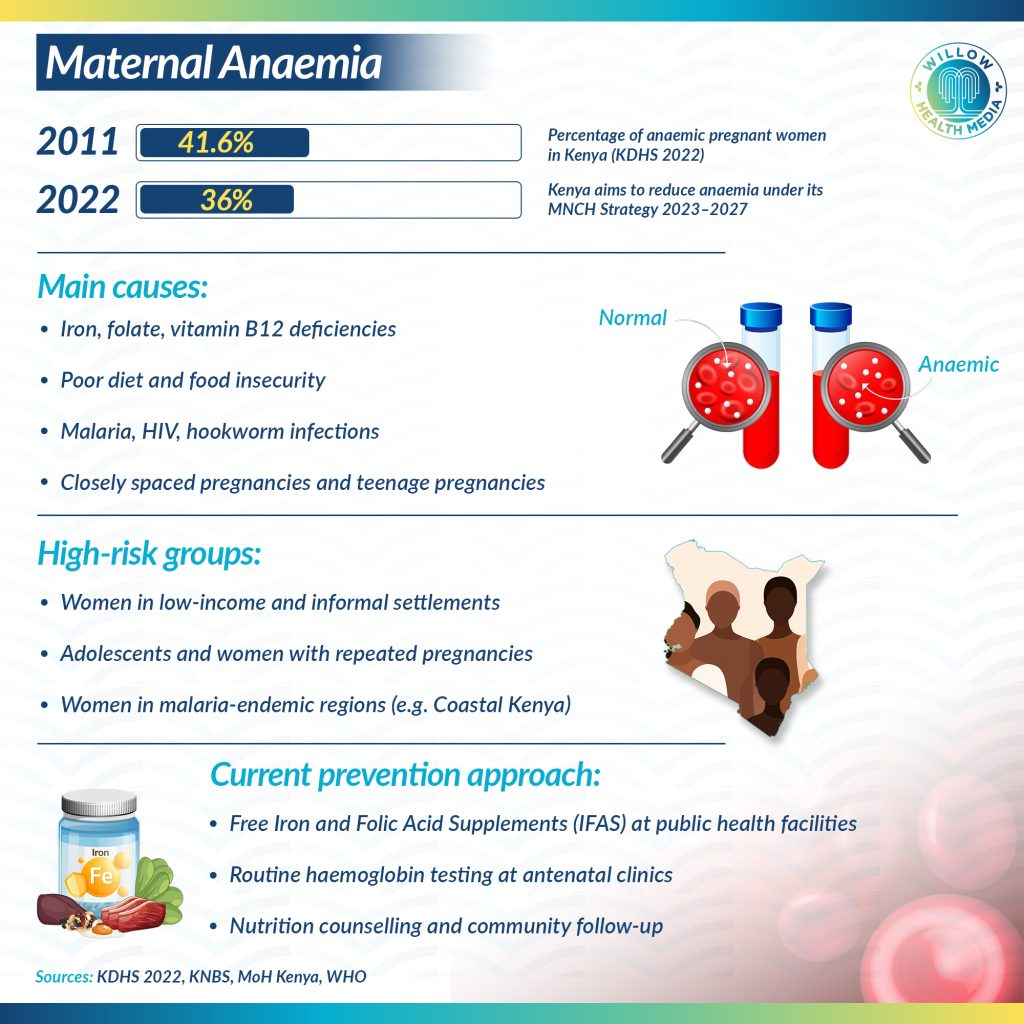

Linda’s experience reflects a widespread and stubborn public health challenge. According to the 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS), about 41 per cent of pregnant women in Kenya are anaemic, a figure that has barely shifted in the past decade. The Ministry of Health (MoH) estimates that maternal anaemia contributes to at least one in every five maternal deaths in the country.

Dr Kibet Shikuku, a haematologist, explains maternal anaemia as “insufficient blood circulating in the body, making one unable to function properly.”

During pregnancy, anaemia develops when blood levels drop because of blood loss or a lack of key nutrients needed to produce healthy blood. “Blood requires ingredients,” he says. “Iron is one of the most essential, and when it’s lacking, the body can’t make enough red blood cells. That’s why some women crave soil or stones, it’s called pica, often linked to iron deficiency.”

Other vital nutrients include vitamin B12, vitamin C and folate. A deficiency in any of these interferes with oxygen transport, leaving women weak and unable to perform daily activities. “When a woman has low haemoglobin, her heart works harder, her concentration drops, and she feels constantly drained,” Dr Shikuku warns. “It’s not just tiredness; her organs are literally struggling for oxygen.”

I felt dizzy most of the time. I ate greens and fruits daily, but nothing changed

For 19-year-old Amanda Ayuma, anaemia set in weeks after she became pregnant in October 2024. “I was so nauseous, I wasn’t eating, I couldn’t even drink water,” she recalls. Doctors prescribed iron and folic acid tablets, then Ranferon syrup when her condition failed to improve. By the time she was due to give birth, her haemoglobin level stood at 9.2.

At Kangemi Health Centre, health workers referred her to Pumwani Hospital in case she needed a transfusion. “In case of excessive bleeding, they could not manage it.” Though her delivery was safe, the experience left her shaken. “I felt dizzy most of the time. I ate greens and fruits daily, but nothing changed.”

Clinicians say Amanda’s case is far from unusual. At Tassia Kwa Ndege Hospital, nurse Vivaline Odhiambo says pale lips, tired eyes and brittle nails are subtle warning signs she sees almost daily. “Middle-class mothers are mostly okay. But for those in low-income areas, anaemia is a major challenge because of diet and affordability.”

She first checks tongues, eyes and fingernails for pallor before sending women for haemoglobin tests. “Anything below 10 is worrying,” she explains. “She needs urgent management to be safe by the time of delivery.” Ideally, treatment involves iron and folic acid supplements, known as IFAS, but shortages are common. “Sometimes we get 100 doses a month, then 112 mothers turn up. When drugs run out, we tell them to buy, but many can’t afford them.”

She refused referral to a bigger hospital. She bled heavily during delivery. We lost her.

More advanced multiple micronutrient supplements (MMS), recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), are still unavailable in most public hospitals. Follow-up is also strained. “Sometimes there’s only one nutritionist in the entire hospital,” Vivaline says. “Many women miss proper counselling because of that.”

The consequences can be deadly. One night, a woman arrived in labour with a haemoglobin level of eight. She refused referral to a bigger hospital. “She bled heavily during delivery. We lost her. The baby survived,” Vivaline recalls quietly. “That’s how dangerous anaemia can be.”

Nutritionists argue that a poor diet remains a major driver. Nairobi-based nutritionist Lillian Mumina says a pregnant woman needs about 30mg of iron daily, ideally from eggs, beans, lentils, meat or traditional greens. “You don’t need expensive foods,” she says. “Githeri (boiled corn and beans), spinach and managu (African Nightshade) are nutrient-rich and affordable. And avoid tea during meals, it blocks iron absorption.”

The Ministry of Health has begun replacing single iron-folate tablets with multiple micronutrient supplements that include iron, folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin D. “A pregnant woman doesn’t just need iron,” Mumina says. “She needs a whole range of nutrients to support her and the baby.”

Still, Dr Shikuku cautions that nutrition alone does not tell the whole story. Malaria, HIV , and hookworm infections also play a significant role by destroying red blood cells or suppressing their production. “Infections play a key role,” he says. “They can destroy blood cells or block the bone marrow’s ability to make new ones.”

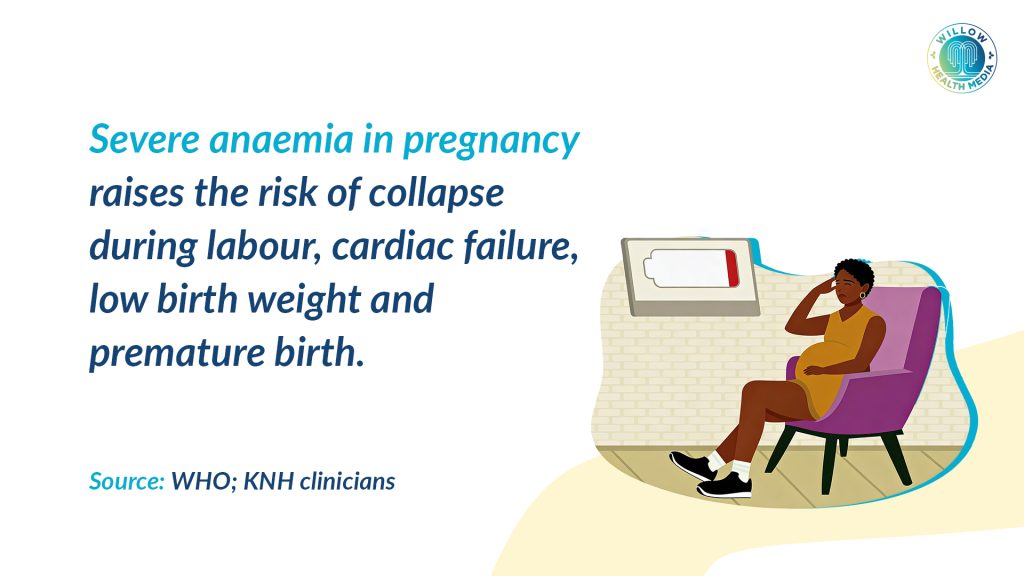

Severe anaemia can cause collapse during labour, cardiac failure, increases risk of low birth weight

Dr Flaviah Ogutu, a gynaecologist and fetal-maternal specialist at Kenyatta National Hospital, calls maternal anaemia a “silent but serious risk.”

“A woman may think her tiredness or dizziness is normal in pregnancy, but sometimes it’s her body struggling to get enough oxygen,” she says. Severe anaemia can cause collapse during labour, cardiac failure, and increase the risk of low birth weight, premature delivery and developmental delays in babies.

In Kenya, a haemoglobin level below 11 g/dL is considered anaemic. Yet further testing, such as ferritin to assess iron stores, remains unaffordable for many, costing up to Ksh 5,000 in private laboratories. While the government provides free IFAS at public clinics, adherence is a challenge. “Iron is not a very nice drug to take,” Dr Shikuku admits. “It causes nausea, constipation and stomach irritation. Many women stop taking it.”

Policy responses are in place. The Kenya Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Strategic Plan 2023–2027 aims to reduce anaemia through early antenatal care, dietary counselling and education. KDHS 2022 data show some progress, with anaemia prevalence among pregnant women dropping to about 36 per cent. Still, only 67 per cent take iron and folic acid as recommended.

Globally, WHO estimates that more than 32 million pregnant women suffer from anaemia, mostly in low- and middle-income countries, and has set a target to halve anaemia among women of reproductive age by 2030. Kenya has aligned itself with this goal, but experts say implementation and awareness remain the weakest links.

“We have the policies,” Dr Shikuku says. “But we need every woman, every household and every health worker to understand that anaemia is not normal.”