Fishermen suffer from eyesight problems, skin conditions, injuries, cuts, sunburns, psychological stress and divers who hunt for lobsters or octopus “Many end up deaf in old age.”

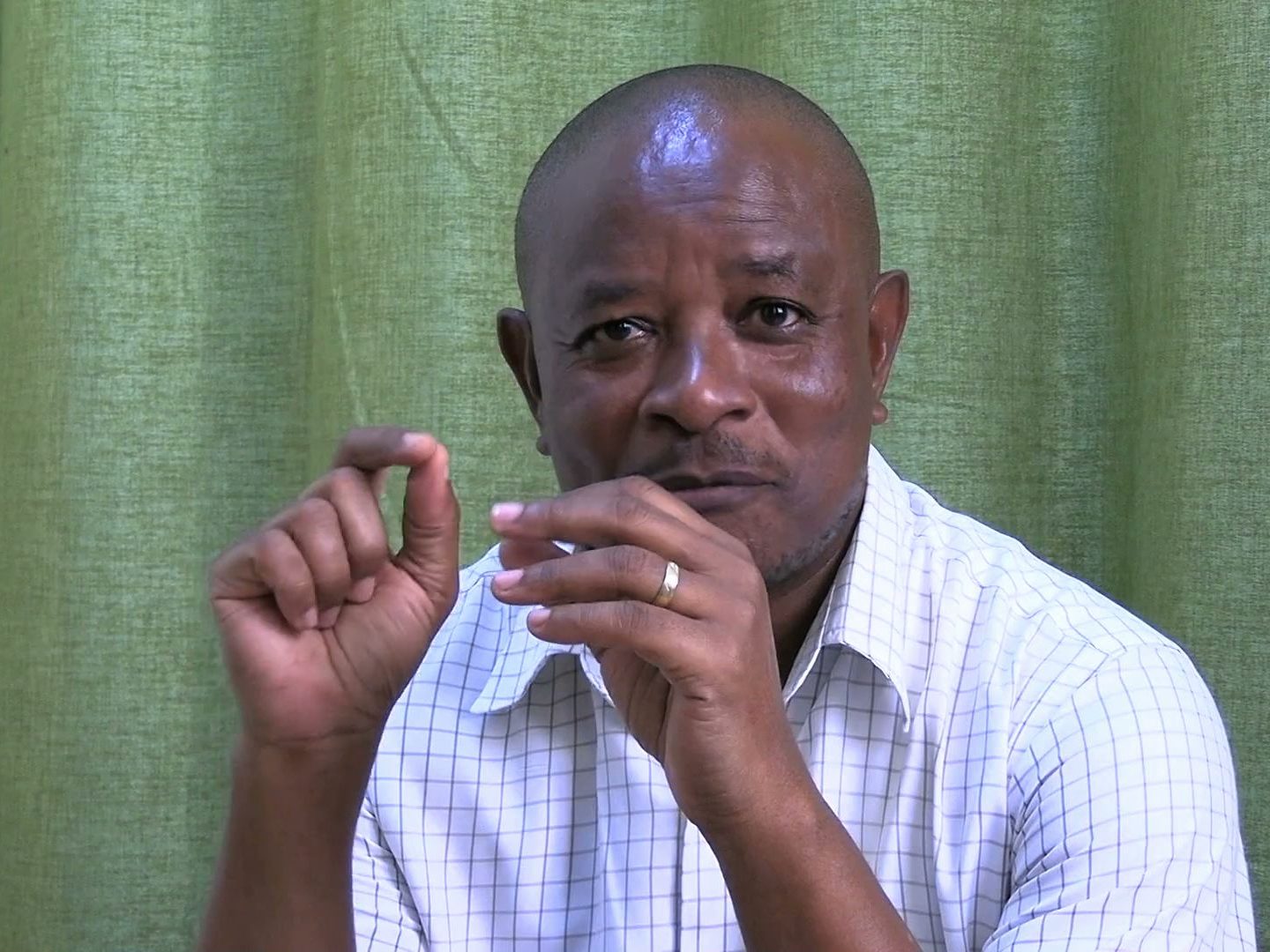

Lali Mau Lali, a fisherman with over 30 years of experience, knows his eyesight is failing, but he has never seen an eye specialist. Years of sun and sea glare have damaged his vision, and he can no longer spot reefs or storm clouds – critical skills for any fisherman.

“I know I have a problem with my eyesight, but I have never visited an eye specialist,” says Lali, who hails from Vanga, over 130 kilometres from Mombasa – a four-hour journey on public transport- if he sought eye care.

Lali recalls visiting an eye camp years ago in his village, but it offered little help. “They just gave us glasses after paying Ksh100, but even then, we were told to go to Mombasa for further screening.”

His failing vision creates dangerous situations. Like the time “I unknowingly drifted into the Marine National Park. I couldn’t see the reefs I usually use as boundaries.”

Lali lists other health conditions as including skin conditions from prolonged sun exposure, night-time cold worsening skin cracking and hearing among divers hunting for lobsters and octopus “Many end up deaf in old age.”

Nassoro Diwani, also from Vanga, has in 30 years, tried line fishing, deep-sea diving, ring net fishing and other “fishing styles because of health issues.”

Some of my friends quit fishing after going blind or becoming permanently deaf

Nassoro says line fishing left him with hook injuries. Diving affected his hearing and eyesight. Now, with ring net fishing, visibility remains a problem due to freezing nights and “Those with asthma suffer frequent attacks. Most of us lack proper cold gear.”

Nassoro urges the government to raise awareness, as fishermen hardly seek medical help and “Some of my friends quit fishing after going blind or becoming deaf permanently.”

Nearly 200 kilometres away in Mkupe, seasoned fisherman Abdallah Kitondo recalls being admitted to the Coast General Hospital for nearly a month, “I lost strength and turned dark.”

He recovered, but “I haven’t felt the same since” and now believes pollution around Mombasa and Kwale affects sea conditions and fisher health.

“Diseases we never knew are now common, like diarrhoea; we never had them. Climate change has brought about more frequent illnesses; eye problems, skin diseases and rashes,” adds Kitondo, singling out protective gear as one of the biggest challenges.

“Many can’t afford sunglasses or gloves. Life jackets are the only protection most of us have.”

Fishermen have no basic training in first aid or how to handle emergencies at sea

Polarised fishing sunglasses cost Ksh2,000 on the lower side, while non-slip fishing gloves go for about Ksh500. Fisher folk making less than Ksh500, depending on the season, can hardly afford.

Kitondo also says fishermen have no basic training on first aid or how to handle emergencies like deep cuts, drowning, or marine accidents, as most hardly have safety drills or rescue simulations.

“If someone gets hurt or collapses, we don’t know what to do. We just try rushing them to shore, but if you are alone, you may even die”, says Kitondo.

Hamid Omar, Chairman of the Wavuvi Association of Kenya, says common health conditions among fishermen “range from skin infections…this year alone, we have received 15 to 20 cases of kidney disease,” and fundraising is common to offset bills.

According to data from the Social Health Authority (SHA), a kidney transplant can cost up to Ksh700, 000 but most fishermen cannot afford the annual premiums, says Kitondo, who’s registered but hasn’t paid.

A 2019 study by Faith Waithera Ngaruiya, George Morara Ogendi and Millicent Mokua published by Environmental Insights Journal on occupational health risks among fisher folk in Kampi Samaki, Lake Baringo, revealed that their jobs expose them to physical, chemical, and ergonomic hazards, which are workplace situations that cause wear and tear on the body and can cause injury.

Each year, about 2.78 million workers die from occupational accidents and work-related diseases globally

These include repetition, awkward posture, forceful motion, stationary position, direct pressure, vibration, extreme temperature, noise, and work stress; thus, they can affect productivity and prolonged absences from work.

Despite the crucial role as cogs in food security and economic development, their health challenges remain largely overlooked.

According to the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury, 2000-2016: Global Monitoring Report, each year, an estimated 2.78 million workers die from occupational accidents and work-related diseases globally.

In 2022, a study by The FISH Safety Foundation, conducted with support from The Pew Charitable Trusts on Fisher Mortality Brief, more than 100,000 fishing-related deaths occur each year worldwide. The study draws attention to the harsh reality that many of these deaths were, and are, avoidable. Incredibly, few were even officially recorded.

Furthermore, the study reports that the 22 member States of the Ministerial Conference on Fisheries Cooperation among African States Bordering the Atlantic Ocean have a yearly fatality rate of approximately 1,000 per 100,000 fishers, which is over 12 times the rate the FAO used for its most recent global estimate of fisher deaths.

Contributing to the region’s high fisher mortality rate are deaths within the sizable artisanal fleet. Additional contributing factors to fisher deaths in this region are overfishing and climate change, which both affect fish abundance in local waters and increase the time at sea and at risk for fishers.

However, in some cases, fishermen survive to tell the story. In December 2023, three out of four fishermen were rescued by a Chinese Vessel after 22 days surviving on raw fish and rainwater after they went missing in a fishing expedition in Malindi.

Doctors feared more than dehydration for the survivors, because such survivors of prolonged exposure to sun, saltwater and a diet of raw fish commonly arrive with severe fluid and electrolyte imbalances, infected wounds and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), considering the gravity of the situation they were in.

According to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, exposure to seawater and shellfish raises the risk of Vibrio infections that can cause rapidly progressive wound infections and sepsis. Research in International Maritime Health shows that maritime disaster survivors often show significant post-traumatic and depressive symptoms, where the prevalence of PTSD among direct victims was estimated to be between 30-40 per cent.

Rescuing a lost fisherman isn’t just about food and water; it’s about healing both body and mind. First is emergency care comprising rehydration, treating wounds and infections, and restoring nutrition. Then, mental health support, including checking for trauma and stress.

Prof Cosmas Munga, a marine and fisheries scientist at the Technical University of Mombasa, says climate change has worsened the situation as erratic weather and rising temperatures affect not just fishing yields, but also fisherfolk’s health.”

Prof Munga explains that increased sea salinity impacts fishing routines and physical wellbeing, while “heat exposure and glare reflection from the sea contribute to long-term conditions like skin cancer and eye degeneration.”

Dr Crystal Serena Vulavu, a medical officer specialising in Occupational Health and Safety, agrees: “Fisher folk face physical, mental, and psychological health challenges. These include musculoskeletal injuries, cuts, sunburns, and severe psychological stress due to income instability.”

She compares fishermen to jua kali workers, but says fishermen suffer ear damage from diving and prolonged exposure to cold or saltwater and thus, “Their risk for psychosocial stress and chronic conditions is much higher.”

According to ILO/FAO report on Safety at Sea for Small-Scale Fishers 2021, long hours, irregular income, and harsh working conditions can push some fishermen toward heavy alcohol use or khat chewing as coping mechanisms. Substance abuse can worsen accidents at sea, impair judgment, and make existing health problems more dangerous.

Charity Kasina, an ophthalmic clinical officer and cataract surgeon at Kwale Eye Centre, warns that sun exposure and sea glare lead to eye damage and “We frequently see keratosis, where the cornea is damaged due to UV rays. In severe cases, this leads to cataracts or permanent blindness.”

She stresses that some conditions, like cataracts, are reversible, but timely intervention is crucial. Kasina also cautions against using seawater to treat eye infections, calling it harmful due to high salinity.

“Fishermen should wear protective sunglasses. The sun and salt can cause severe, sometimes irreversible, damage,” she advises.

Kenya’s Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA) of 2007 recommends safe working environments and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, it’s rarely enforced in informal sectors like fishing.

Kenya lacks key specialists in occupational diving medicine, hyperbaric treatment, and public health entomology. Publicly available data show about 150 psychiatrists nationwide, making the mental health toll on fisherfolk to remain a distant goal.

Diving-medicine capacity appears to be limited mainly to military facilities in the country. A small number of private hospitals in the country offer hyperbaric oxygen therapy, but there is no public registry listing nationwide coverage of it or formally trained diving medicine specialists.

While Kenya signed the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) Fisheries Convention, it has yet to adopt many of its provisions into local policy.

Omar of the Wavuvi Association laments how “we are consulted on fishing zones and life jackets, but no one talks about our health.”

Dr Vulavu urges Kenya to follow South Korea in collecting annual data on injuries, work absences, and safety protocols in the fishing industry, besides the application of basic prevention: “Even simple steps like wearing gloves and hats can significantly reduce harm.”

Roman Shera, County Executive Committee Member for Agriculture and Fisheries in Kwale County, acknowledges the problem.

“We have empowerment programs for fishermen, but it’s time for targeted interventions on health. Fishermen often miss medical camps due to their schedules. Those who fish at night sleep during the day.”

He says the county is working on plans to bring health services closer to landing sites and integrate health into blue economy initiatives. Despite this economic importance, the sector is crippled by poor health infrastructure, a lack of protective gear, and policy gaps.

“We want our health taken as seriously as our safety at sea,” says Omar.

From the dhows of Coastal Kenya to the beaches of Lake Region, Kenya’s fishermen face dangers that run deeper than the waves. A closer look shows the coast could learn life-saving lessons from the lake. But with targeted and intentional approaches, there could be a shift in conversation from the dangers of fishing to the health of those who keep Kenya’s waters alive.