‘I haven’t met anyone in Africa with the same chromosomal anomaly as my child,’ says Christine Mutena. In Kenya, there’s no official system tracking rare diseases like Chromosome 18.

When Christine Mutena had her second daughter 13 years ago, she thought she knew what to expect. Her first child already had a rare condition, so doctors focused on looking for that same disorder during pregnancy. But this time was different, and they missed it.

“She was born with intrauterine growth retardation. She was too small for her age, but it wasn’t picked up because we were looking for something else her sister has,” Christine recalls.

As the baby grew, she was “a bit floppy,” with weak muscles. By six months, she still couldn’t sit up. Christine, a computer scientist, didn’t have a clear picture of normal baby development. Her older daughter also had a rare genetic condition, making each stage unfamiliar. This meant the delays didn’t alarm her as much as they might other parents.

When her youngest was around two, a physiotherapist called her at work and said, “I think your child has Down syndrome,” sending Christine into frantic online research.

Her doctor ordered a karyotype – a genetic test that looks at chromosomes. The samples from Metropolis in Parklands, Nairobi, were sent to India for analysis. The report showed a Chromosome 18 problem. At the bottom, three words stood out: “Genetic counselling recommended.”

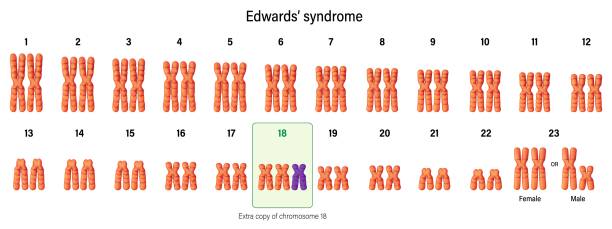

Chromosome-18 disorders comprise many conditions, including Edwards syndrome

According to Pathcare Kenya, genetic testing is available in public and private hospitals, including Kenyatta National Hospital, Aga Khan University Hospital, Gertrude’s Children’s Hospital, Nairobi Hospital, MP Shah Hospital, Avenue Healthcare, and Karen Hospital. Independent labs like Pathcare Kenya also offer genetic tests, often working with facilities in South Africa. Christine’s daughter’s results left her with more questions than answers.

Chromosome-18 disorders include many conditions, from full trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome) to partial problems with parts of chromosome 18. These conditions vary greatly – some people have life-threatening complications while others live into adulthood with developmental and medical needs. Trisomy 18 happens in about 1 in 6,000–8,000 live births, while partial problems are much rarer. For families, this means one family’s experience may be very different from another’s, even with changes on the same chromosome.

Christine found help through the Chromosome 18 Registry & Research Society, a parent-led group based in the US that connects families worldwide. The Society also funds research.

Finding a case in Africa like Christine’s is very rare, not because the condition doesn’t exist here, but because it’s often misdiagnosed or not detected.

“So far, I haven’t met anyone in Africa with the same chromosomal anomaly as my child. I’ve connected with a few families in Europe and the US, but never from Africa,” Christine says.

Dr Catherine Mutinda, a geneticist and paediatrician, warns against giving diseases general names without proper genetic testing. A confirmed result shows exactly which part of the chromosome is affected and helps predict symptoms. “Without that precision, you risk missing the full picture of the condition,” she says.

Caring for two children with complex medical needs heavily impacted Christine’s work life

Rare diseases affect about 300 million people worldwide, with over 7,000 known rare conditions, according to Global Genes, Rare Disease Facts, 2025. In Kenya, there’s no official system tracking rare diseases.

Caring for two children with complex medical needs heavily impacted Christine’s work life. Hospital appointments and specialist visits came in waves – some weeks one specialist, the next week another. Employers struggled with the unpredictability.

As the only income earner, Christine’s monthly care costs for both daughters run into hundreds of thousands of shillings. When they were younger, costs were even higher – they needed special equipment like standing aids, stability balls, and walking frames before they could move around. Today, costs vary depending on their health, with routine check-ups every three months still necessary.

She also faced problems with nannies and house workers who “would come and go,” many unable or unwilling to handle the feeding, medication schedules, and clinic visits her children needed. “You ask yourself, ‘Is it worth risking my child’s life?'” she says.

Eventually, Christine left her job to become her children’s full-time caregiver, ensuring they were healthy, comfortable, and well-fed. It was a choice she’s proud of. Her family has been a strong support system throughout. “I always say I did the best for them with what I had. It wasn’t easy at the time because it felt like I had walked away from an income to stay home with them, but it was the right decision,” she reflects.

Private health insurance policies exclude birth conditions or have a very low coverage limit

Rare genetic conditions create money problems in many ways: ongoing medical care, repeated hospital stays, special medicines or devices, and often higher school costs or specialised education needs. Insurance adds another problem. Many private health insurance policies in Kenya exclude birth conditions or have very low coverage limits, leaving families to pay most costs themselves, according to Amssurity Insurance Agency in Kenya.

Christine recalls how her insurance refused to pay her first daughter’s medical bills, calling the condition congenital. “When my second-born was diagnosed with Chromosome 18 anomaly, I was told, ‘hers is chromosomal, which is even worse,” she says. While Kenya’s Social Health Authority (SHA) covers many hospital services, gaps remain for specialised genetic care, ongoing outpatient management, and expensive medications often needed for rare conditions.

For many Kenyan parents of children with rare conditions, the cost of care forces impossible choices between work and caregiving.

Because of learning challenges, Christine homeschools her daughters, occasionally hiring a teacher. While they do attend school, they learn at a different pace from other children their age. Kenya’s education system has limited support for children with developmental disabilities, though recent policy changes have emphasised inclusive education. The cost of their specialised education runs into hundreds of thousands of shillings, as they need more intensive care and support than their peers.

Still, Christine moves them to the next class each year, not just for academics, but to keep the important social connections that keep their world open and engaging. “I was taught never to shy them away from society. How I treat them is how society will treat them. They have become my pride and joy.”

She co-founded Rare Disorders Kenya (RDK) which advocates for awareness, care, and medicines

Christine turned her private struggle into a public purpose. She co-founded what began as small awareness efforts into Rare Disorders Kenya (RDK), a patient-led group based in Nairobi that advocates for awareness, improves access to specialist care and medicines, and pushes for data and policy change so rare diseases are visible in national planning.

Since starting, RDK has encountered 125 different conditions and has supported hundreds of people living with rare disorders – adults and children with their parents.

The organisation provides peer-to-peer support for individuals and families affected by rare disorders, but does not offer financial help. While most members are Kenyan, the organisation also gets inquiries from people of other nationalities, who are then connected to relevant networks in their own countries. Medical professionals often refer patients to RDK for peer-to-peer support.

“The seed that was planted when I was desperately searching for answers for my daughter outweighs any degree I’ve ever earned. When your passion and purpose align, nothing in life can be greater,” she says.

Christine wishes her daughter’s diagnosis had come decades later with genetic counselling

That push has global echoes. The World Health Organization (WHO) adopted its first resolution on rare diseases in 2021, calling on member states to include rare diseases in national health plans and ensure fair access to diagnosis and treatment. For Kenya, this could mean developing rare disease registries, training healthcare workers, and changing insurance policies to include chronic and rare conditions.

Christine sometimes wishes her daughter’s diagnosis had come a decade later, when geneticists and genetic counselling were easier to access in Kenya. She appreciates the progress on genetic services, civil society is louder, and international registries and WHO momentum mean a different future for the next child diagnosed. “Kenya’s genetic service landscape is stronger than in many East and Central African countries, yet it still lags behind South Africa in institutional capacity and training infrastructure”, notes the 2024 Journal of Community Genetics.

For now, Christine continues her fight, not just for her daughters’ care, but for recognition, policy change, and a healthcare system that understands that rare does not mean invisible. And every day, as she holds her girls close, she knows their lives show strength, love, and the hope that tomorrow’s Kenya will be ready for children like them.