The situation is worsened by the Ksh10 million owed by NHIF to dialysis service providers, with no formal mechanism to address it

John Ngao Matheka, a dialysis patient from Machakos County received a text message that he would be paying out of pocket, shortly after the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) transitioned to Social Health Authority (SHA) in October 2024.

Matheka, who has been undergoing dialysis at Machakos Level 5 Hospital, previously used his NHIF card for dialysis services at a private facility with costs ranging between Ksh9,500 to Ksh12,000 per session, which translates to Ksh76,000 a month for eight sessions.

Paying out-of-pocket troubled him: He lost his job after falling ill and the few cows and goats the family owned were sold to cater for his medication and the Ksh600 for transport from his home in Kangundo to Machakos.

When Willow Health reached out to him late last year, he wondered “how I am going to survive yet even walking has become a huge issue without dialysis. I cannot sleep well. I cannot eat well and even sitting is a problem. My entire body is full of pain and if I do not get dialysis, I think I might die.”

When SHA was being rolled out, several healthcare facilities had not signed the formal contracts as directed by SHA, and therefore, could not admit or discharge patients under SHA. Providers also said there was lack of an operational digital claims system under SHA and that they were uncertain about their legal standing.

At the time, Matheka had not registered under SHA as the guidelines were unclear, and there were several complaints of system delays.

However, in our recent meeting, he had registered under SHA and had moved from getting dialysis services from the private facility to Machakos Level 5 Hospital.

“They asked for my ID followed by several questions like where I work, and I am not working, and the number of children I have of which I am the only one supporting my family by doing simple menial jobs at my home village,” said Matheka of the Means Testing process which helps jobless and self-employed Kenyans assess their monthly contributions to SHA.

From this, he was required to pay a monthly contribution of Ksh1,030 or an annual contribution of Ksh10,600, whereby, under NHIF, he was required to pay a monthly fee of Ksh300 and get dialysis services worth Ksh9,500 per session.

But Matheka is wondering why he was required to pay such a huge amount, yet he knew people who were making smaller contributions. Matheka is requesting the government to reduce the monthly contribution to Ksh300 that he used to pay under NHIF, which is also the minimum contribution under SHA for salaried and non-salaried households.

Under the NHIF, a patient would benefit from the payment of Ksh960,000 annually based on Kshs9,500 per dialysis session for two sessions each week, while under SHA, a dialysis patient will get Ksh1,192,800 based on Kshs10,650 per session for a maximum of three sessions each week.

Late last year, the Kenya Renal Association raised concerns about the dialysis patients who were unable to register under SHA system, leaving them with no option but to make out-of-pocket payments for the life-saving dialysis treatment.

“Dialysis providers are without formal contracts as directed by SHA,” the association said. “The promised digital contract system has yet to be implemented, leaving providers uncertain about their legal standing.”

However, by the end of October 2024, the Ministry of Health reported that all public health facilities and over 60% of the private healthcare facilities had been contracted by SHA and were to provide services seamlessly.

The Kenya Renal Association had also said “the current disarray in a health insurance scheme of such critical importance is unacceptable,” a situation that was worsened by a pending bill owed to medical facilities by NHIF.

In October last year, Chairman of the Kenya Renal Association Dr Jonathan Wala released a statement indicating that NHIF owes dialysis service providers more than Ksh10 billion in unpaid claims, with no formal mechanism in place to address the crippling debt, leaving vulnerable kidney patients across Kenya in jeopardy.

Regarding SHA claims settlement, a survey conducted recently by the Rural and Urban Private Hospitals Association of Kenya (RUPHA) indicated that higher-tier facilities (Levels 5 and 6) where most of the dialysis services are offered received their payment consistently compared to primary care facilities (Levels 2 and 3), but were still experiencing challenges in the NHIF arrears payments across all healthcare facilities by the end of December 2024.

According to RUPHA, 49% of facilities received no NHIF arrears payments, 40% received the NHIF payments, while 11% were unsure of the payment’s purpose.

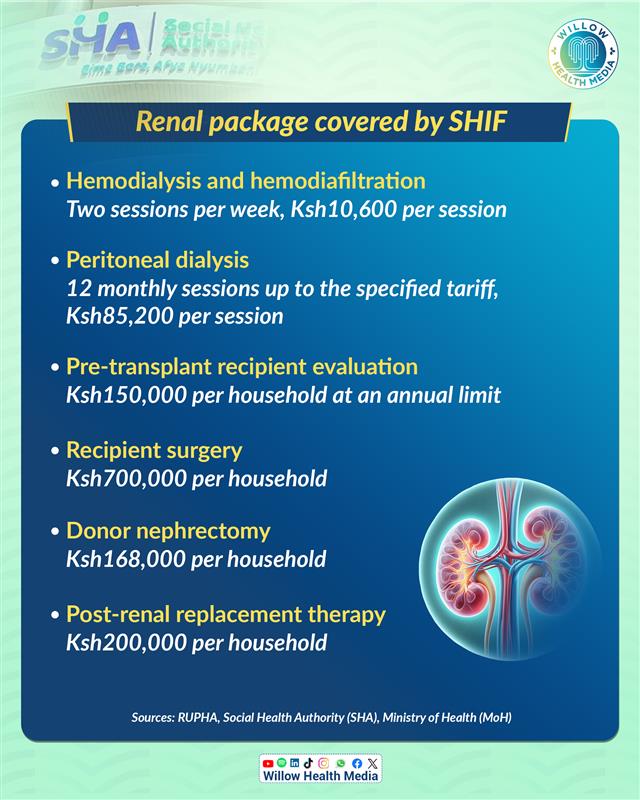

Under Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), the renal services package includes consultation and specialist review, the cost of the temporary catheter and insertion/removal, nursing care and dialysis services.

It also includes routine laboratory investigations such as Urea Electrolytes and Creatinine (UECs) full Haemogram and blood glucose, dispensation of medication and maintenance drugs including Erythropoietin injection continuous intermitted dialysis and other dialysis protocols.

It also includes renal replacement therapy that has pre-transplant recipient evaluation, kidney transplant and post-renal replacement therapy.

These services can be offered in Level 3-6 facilities with the capacity to offer renal services.

In a Gazette notice, SHIF will pay Ksh10,600 per session for Hemodialysis and hemodiafiltration, catering for two sessions per week, and Ksh85,200 per month for peritoneal dialysis catering for 12 monthly sessions up to the specified tariff, Ksh150,000 per household for pre-transplant recipient evaluation at an annual limit, Ksh700,000 for recipient surgery, Ksh168,000 for donor nephrectomy and Ksh200,000 for post-renal replacement therapy per household.

According to RUPHA, some of these challenges can be addressed by addressing the disparities in payment disbursement, streamlining the reconciliation processes and ensuring timely and transparent arrears settlements to sustain service delivery.