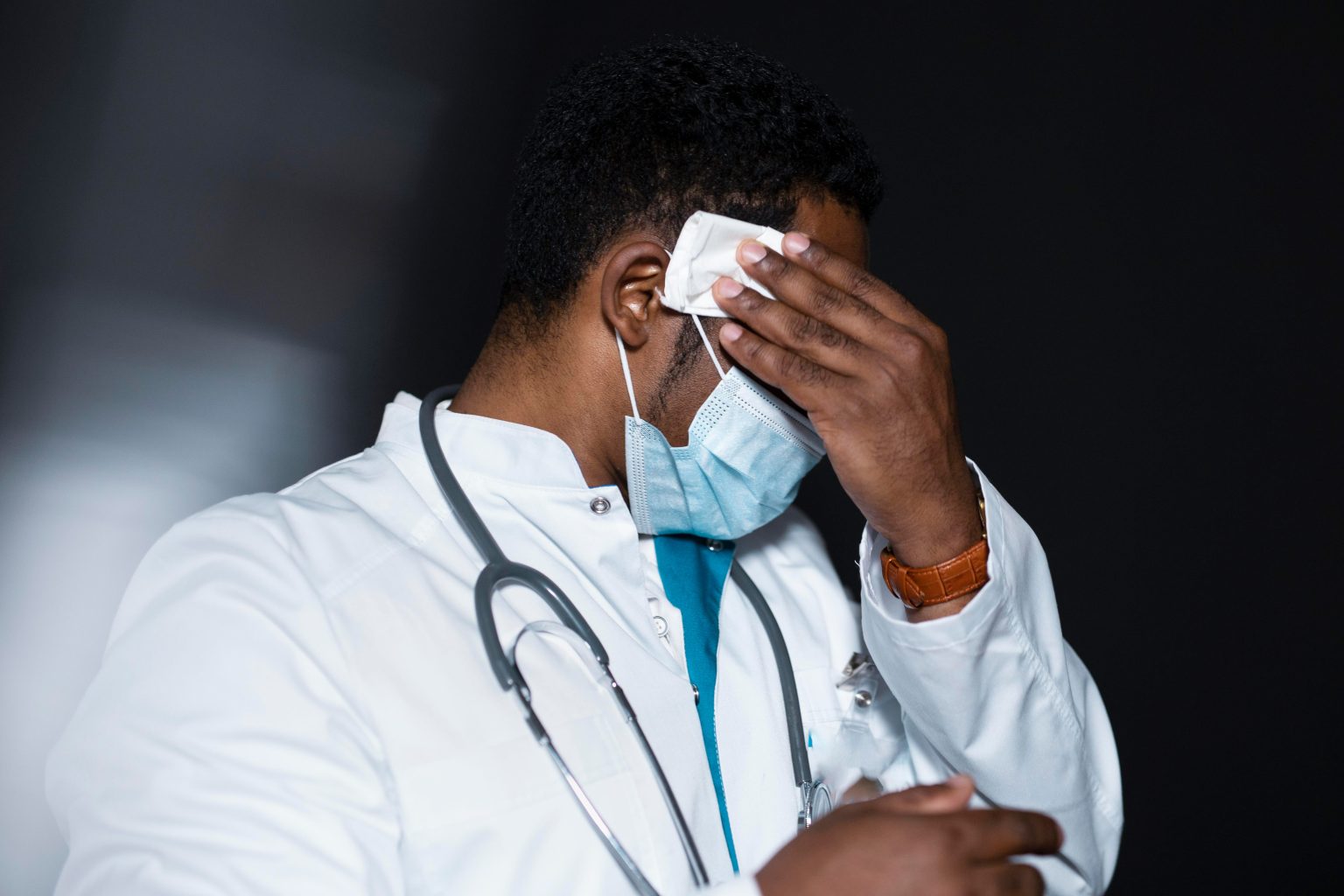

Research shows physicians, surgeons and pharmacists are addicted to morphine, codeine, fentanyl due to knowledge, ease of access- mostly to cope with burnout, stress, anxieties…

In Kenya and other developing countries, doctors and nurses in public hospitals are running on empty—overworked, underslept, and stretched thin by endless lines of patients. The cost of saving lives? Their own well-being.

Understaffing transforms every shift into an exhausting marathon. Moreover, many are subjected to unsafe conditions, including exposure to infectious diseases and insufficient protective equipment, which adversely affect their physical and mental health.

Coupled with managing personal responsibilities, this situation can feel insurmountable. Consequently, many resort to abusing prescription medications such as opioid analgesics, owing to their ease of access, as a means of coping with their reality.

Opioid analgesics such as morphine, codeine, and fentanyl are powerful painkillers but carry a significant risk of addiction if misused. Heroin, on the other hand, is an illegal, highly addictive, recreational drug of abuse, derived from morphine.

Some of the HCPs may turn to heroin when prescription opioids are unavailable.

These drugs cross the blood-brain barrier and impact the reward pathways in the brain. By binding to mu-opioid receptors in these pathways, opioid analgesics enhance the release of dopamine, which is associated with reward and pleasure. The surge in dopamine results in a rush of euphoria followed by a state of relaxation.

Half of Kenya’s healthcare professionals have abused prescription drugs in their lives

Over time, repeated opioid use can modify the brain’s reward circuitry, making it more difficult for individuals to experience pleasure from natural rewards like food or social interactions. This is a critical factor in the development of addiction.

In June 2024, a World Drug Report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) revealed that there were 60 million opioid users globally, making opioids the second most commonly abused drug after cannabis (228 million).

A 2023 study investigating substance use among healthcare professionals in Kenya by Dr Jasmit Shah, a data scientist currently associated with the Brain and Mind Institute of Agha Khan University Hospital, revealed that 51.7% of HCPs have used addictive substances in their lifetime. This is slightly lower compared to the lifetime prevalence of substance abuse by the general population, which NACADA reported to be 53% in 2025.

Some 41.3% of the healthcare respondents reported having used opioids within the last three months, whereas 5.3% reported lifetime use.

In 2024, Dr Daniel Muvengei, a clinical research scientist based in the area of study, conducted a similar research titled Substance Use and Its Correlates among Healthcare Workers in a Teaching and Referral Hospital in South Western Kenya at Kisii Teaching and Referral Hospital.

According to the report, 10.97% of HCPs had used opioids in their lifetime, with 6.33% currently taking them.

Intense daily nature of surgery and life-or-death situations drive higher rates of substance use

Self-prescription of medicines such as opioids by healthcare workers may lead to drug abuse. This alarming trend has been influenced by their medical knowledge, the ease of access to medications, and pressure, anxiety, and discomfort from work.

Dr Shah and fellow researchers found that substance use was more prevalent among the specialities of surgery and internal medicine. The intense nature of surgery and potentially being in life-or-death situations, daily, may drive higher rates of substance use as a coping mechanism for work-related stress. Similarly, the heavy workloads and extended hours faced by internal medicine physicians in Kenya could encourage unhealthy coping strategies, though this hypothesis warrants further exploration.

In 2018, the Daily Nation informed us how pharmacists were abusing prescription drugs by faking patient records to access regulated medicines for which they are the legal custodians.

The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (Cap 245) in Kenya governs controlled drugs such as opioids through strict licensing, prescription guidelines, and monitoring regulations.

It ensures that only authorised businesses and personnel handle these medicines, while also requiring rigorous record-keeping and transaction reporting to prevent misuse. Unauthorised possession, trafficking, or misuse all result in serious consequences.

For instance, a person found in possession of narcotics and psychotropic substances solely for his/ her personal use is guilty of an offence and is liable to 20 years’ imprisonment or a fine of not less than one million Kenya shillings or three times the market value of the seized drugs, whichever is more.

Opioid overdose can result in death within minutes to hours, depending on amount consumed

Self-prescription of opioids and other prescription drugs carries dire consequences, including the risk of developing dependence, which can trap individuals in a vicious cycle of misuse and addiction. Furthermore, opioids might impair cognitive capacities, leading to poor decision-making and judgment, and slow reaction times. This poses a significant threat to the quality of patient care as errors in diagnosis, treatment, or medication administration may occur.

Opioid overdose can result in death within minutes to hours, depending on the amount consumed, the individual’s tolerance, and the speed of medical intervention.

An overdose of intravenous (IV) fentanyl can lead to death in less than three minutes if respiratory depression is severe and no intervention is provided. This is because IV fentanyl has a fast onset of action and a narrow therapeutic index (that is, they have minimal differences between the therapeutic and toxic doses).

Symptoms of opioid overdose include pinpoint pupils, unresponsiveness, and respiratory depression. In the latter, breathing slows or stops, depriving the body of oxygen, hence, the victim’s skin turns pale, clammy, and cold, and the lips and fingernails take a bluish hue.

The onset of opioid withdrawal symptoms can be within six to 48 hours from the last dose, depending on the type of opioid (short-acting versus long-acting), duration of use, and the person’s metabolism.

Early symptoms often resemble the flu. They include muscle aches, sweating, a runny nose, and yawning. As withdrawal progresses, individuals may experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, and goosebumps. Psychological symptoms like anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia are also common. In severe cases, withdrawal can lead to rapid heartbeat, high blood pressure, and intense cravings for opioids.

Opioid analgesics are generally contraindicated during pregnancy. This is because they can cross the placenta and harm the developing fetus. Exposure to opioids in utero can lead to poor growth, birth defects, and Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal Syndrome (NOWS).

Newborns with NOWS typically exhibit symptoms like persistent crying, irritability, feeding difficulties, vomiting, diarrhoea, and trouble sleeping. Additionally, they may experience tremors, convulsions, and increased muscle tone.

Pharmacy and Poisons Board must enforce monitoring for opioid prescriptions and usage within healthcare settings

These symptoms arise as the newborn’s body adapts to the lack of opioids following birth. In severe instances, opioid replacement therapy using medications like morphine and methadone is necessary.

To mitigate the opioid crisis among the general public and healthcare professionals, the government should enhance enforcement mechanisms to ensure strict adherence to CAP 245.

The Pharmacy and Poisons Board must enforce robust monitoring systems for opioid prescriptions and usage within healthcare settings. Regular audits in healthcare facilities and community pharmacies should be conducted to guarantee compliance with safe storage, distribution, and disposal of opioid medications and other controlled substances. Establishing confidential reporting systems for healthcare professionals facing addiction, along with support for rehabilitation programs, can be beneficial.

The Ministry of Health should implement programs educating healthcare workers about the risks of opioid misuse and addiction. Health institutions ought to create confidential and safe support groups for those battling addiction. Additionally, the government should foster a supportive hospital environment by investing in infrastructure, modern equipment, and proper staffing. Healthcare workers should have access to mental health resources to manage stress and burnout.

Finally, further research is essential. By prioritising research, stakeholders can develop tailored solutions to safeguard healthcare providers and the wider community from the negative repercussions of opioid misuse.

Dr Sharon Wambua is a pharmacist and creative non-fiction writer.

From reading this article, I learned that even healthcare professionals aren’t immune to the pressures of their work—they’re human too. It shocked me to find out how many are turning to opioids like morphine and fentanyl just to cope with burnout and emotional stress.