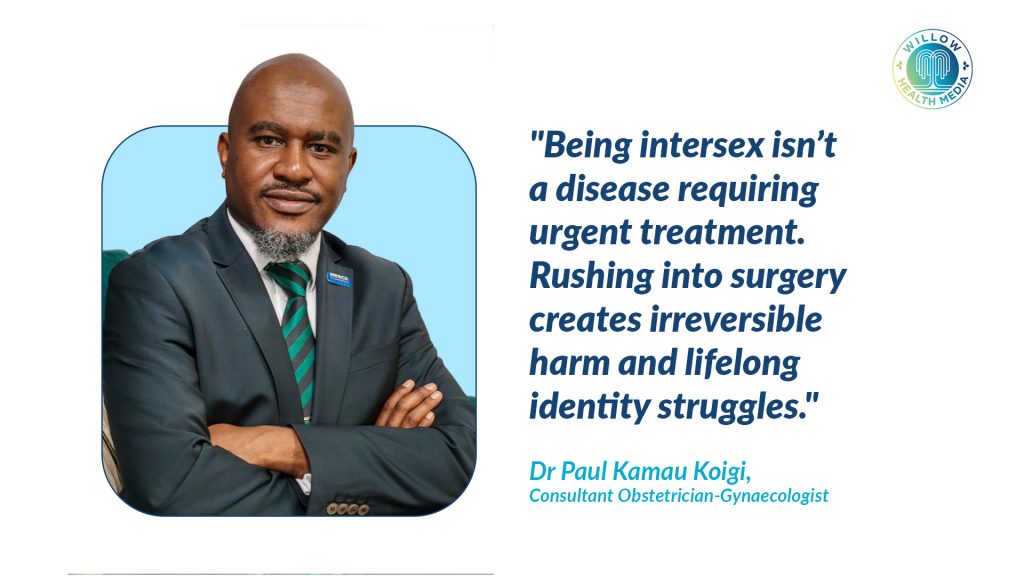

Being intersex is not an ‘urgent disease’ and Dr Kamau Koigi advises parents not to rush into reconstructive surgery.

When Phresha Kagonya delivered her sixth child at Kenyatta National Hospital in June 2000, she had no idea her life was about to change forever.

Her newborn had both male and female organs, a condition that would shatter her family and force her into a journey of survival and acceptance.

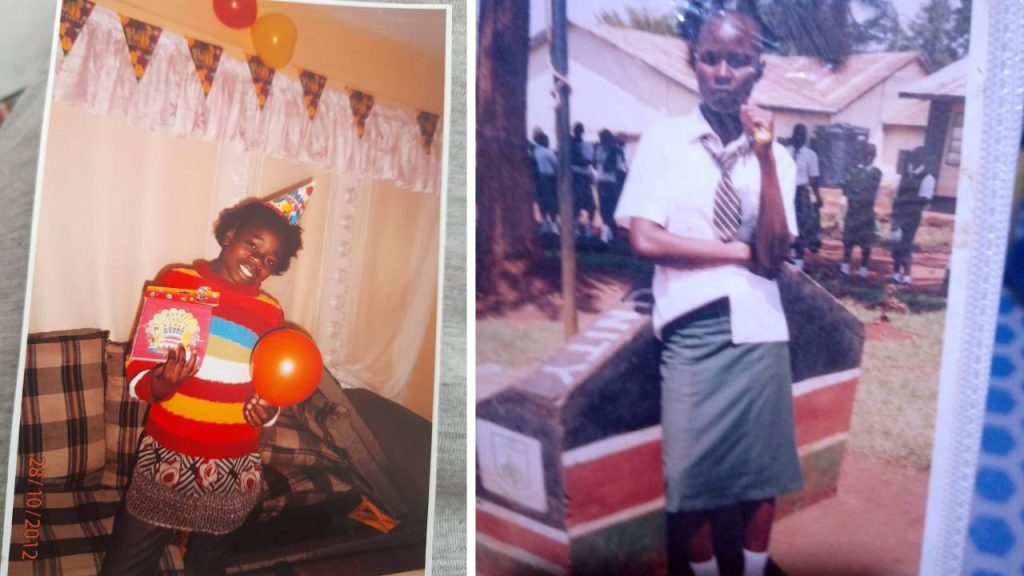

Phresha named the child Diana Aleyo and decided to raise her as a girl. But fear and superstition quickly took hold. The child’s father, gripped by cultural beliefs that intersex children result from extramarital affairs, rejected them both and demanded they leave. Forced to abandon her five older children, Phresha fled to Nairobi with Diana, where friends further urged her to abandon the child, claiming intersex children bring curses. Others went further, advising her to kill the child.

Even Phresha’s own sister wouldn’t accommodate the “strange child,” leaving mother and daughter to fend for themselves on the streets while Phresha took menial jobs to afford a small rental house for them both. This got them settled for a few years, until it was time for Diana to join school.

Phresha feared exposing her child to ridicule, so she strictly instructed Diana to keep her condition secret, but secrets in childhood are fragile things.

Diana watched classmates develop feminine characteristics while her own voice deepened

One day, arriving late to class, a suspicious teacher questioned Diana, leading to a humiliating inspection in the staffroom where she was forced to stand on a table as teachers gawked. The head teacher promptly issued an expulsion letter, declaring her condition a “threat” to other girls.

At the next school, the disparity became more pronounced. Diana watched classmates develop feminine characteristics while her own voice deepened and her body changed. “I was discriminated against and secluded. I felt lost,” Diana recalls. “I was bullied and became a loner. Some parents stopped their kids from playing with me.”

She proceeded with school and did her KCPE. Despite results being issued under the name “Diana Aleyo,” Diana’s body had developed distinctly male characteristics.

It was so apparent that even when Phresha insisted on Diana going into a girls’ secondary school and proceeding to buy pads and dresses, Diana refused.

“I repeated class 8 so that I could finally join a boys’ secondary school with my new identity. Which was then changed to Dalton Musamula,” he said.

But even this transition brought with it new challenges.

“Hiding during showers raised suspicion among my classmates, ultimately leading to another expulsion. That is how my education abruptly ended,” says Dalton. He was only in Form Two.

“I asked mum to help me start a small business instead.”

Gloria was called a tomboy and avoided dormitory showers throughout her school years

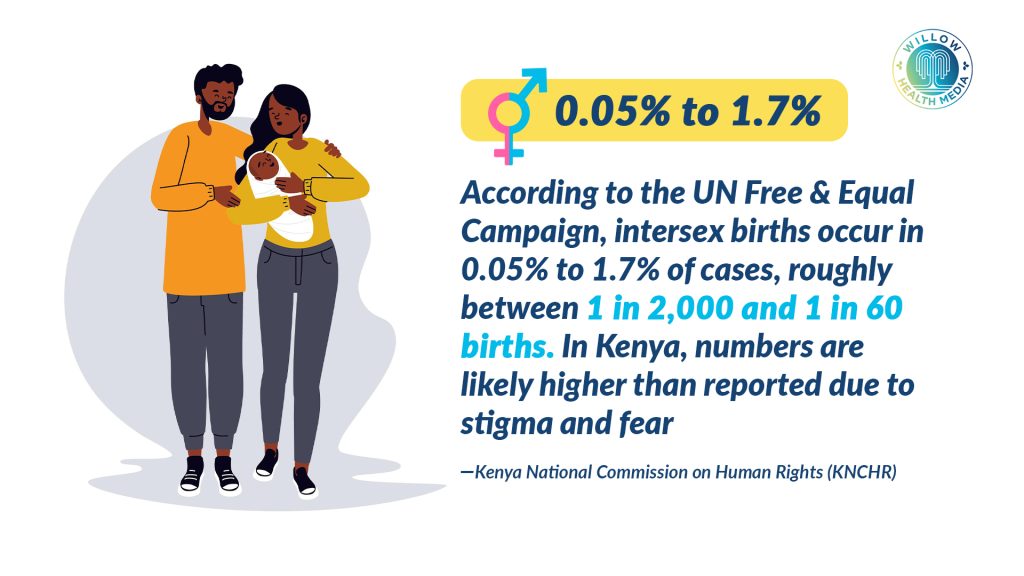

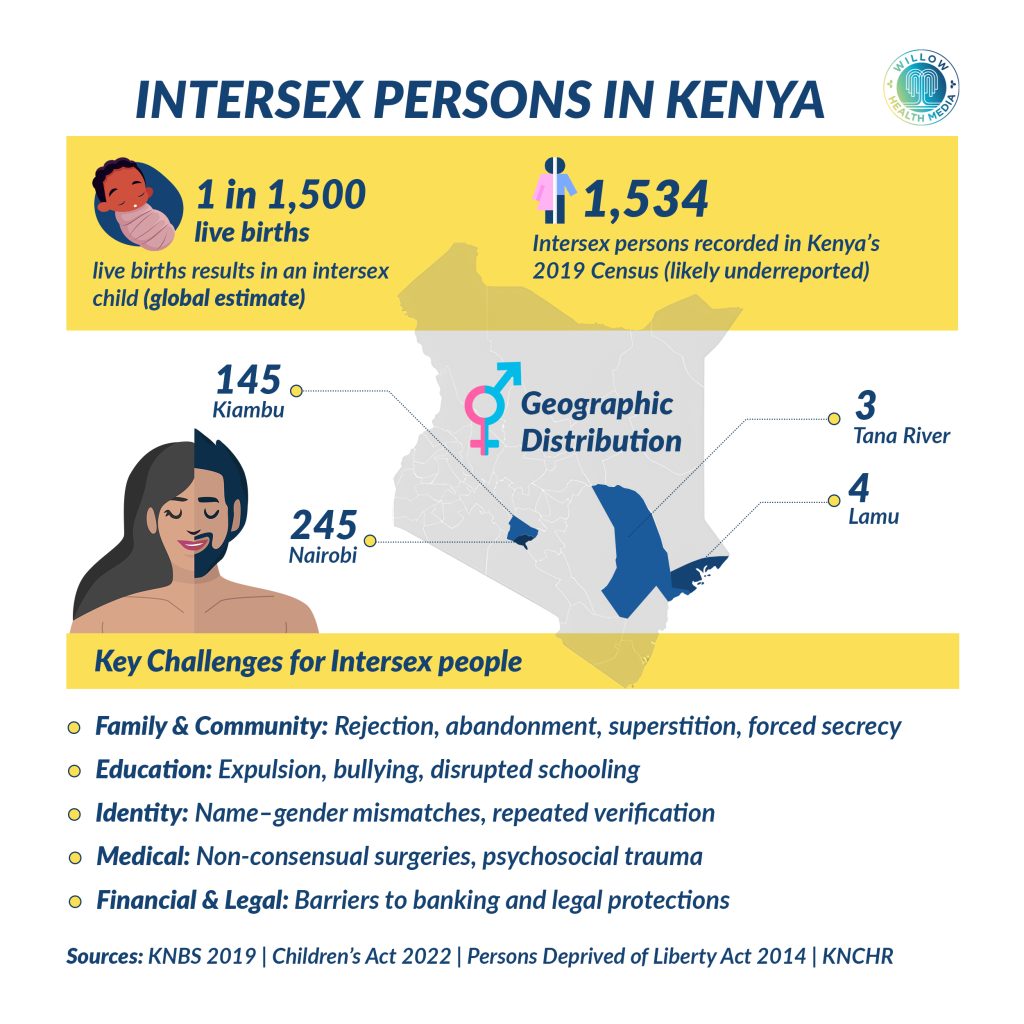

Dalton’s story represents just one of 1,534 recorded intersex persons in Kenya’s 2019 Census, though actual numbers are likely much higher. Nairobi leads with 245 registered intersex persons, Kiambu comes second with 145, and Lamu and Tana River are last with four and three, respectively.

The intersex community in Kenya faces a myriad of challenges, which include mismatched documents, that compound the daily stigma intersex individuals face.

According to Gloria Luhunga, a researcher at the Intersex Persons Implementation Coordination Committee at the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR), intersex numbers are underreported since many register simply as male or female to avoid complications.

Gloria herself, also an intersex person, recalls being called a tomboy and avoiding dormitory showers throughout her school years. “Even now, when I present my ID, people say I’m using someone else’s documents,” she shares, highlighting how document inconsistencies create daily challenges.

To navigate the identity challenges, some individuals have created their own solutions. For instance, an individual who was born Anita Waruguru and later changed her name to Benson said she had to merge both names into “AnitaBen.” “I couldn’t fit into one name, so I combined both,” AnitaBen explained.

Imagine your ID reads Francisca and the person is male, this exposes us daily

For others, like Frankie Kibagendi, the mismatch was created by an early medical intervention. Frankie said that a surgery performed on him as a baby without consent made his body fit the female category, and his parents named him Francisca.

“Now imagine your ID reads Francisca and the person is male,” he explains. “That mismatch exposes us every single day.”

One might think that a parent can detect the sex mismatch even before delivery. Last year, for instance, a young mother we’ll call Tabitha, for her fear of exposure, experienced the confusion firsthand when, after multiple scans declared she was carrying a boy. However, after delivery, the medical staff at the delivery insisted the baby was a girl.

“The doctor insisted it was a girl. They kept checking, opening, and debating. I was confused and thought I was hallucinating,” she recalls.

It was at this moment that she noticed her baby had no testicles; it marked the beginning of a troubled journey that would cost her marriage, family relationships, and job. However, she chose to stick by her child and decided to raise him as a boy, anticipating whatever truth puberty brings.

“I don’t want my child to grow up feeling rejected, so wherever I go, I go with him. I want him to feel our bond is strong,” Tabitha explains.

In the first seven weeks, male and female babies are indistinguishable, says Dr Kamau Koigi

Dr Paul Kamau Koigi, Consultant Obstetrician-Gynaecologist and Reproductive Endocrinology Subspecialist, provides crucial context for understanding how intersex conditions develop.

He explains that in the first seven weeks of development, male and female babies are indistinguishable. “By default, without a Y chromosome and testosterone influence, females typically develop. High testosterone forms male genitalia; low testosterone develops female genitalia.”

However, modern environmental factors increasingly disrupt this natural process. Common causes include exposure to harmful substances during pregnancy, such as radiation, pesticides, contaminated water, soil, and commercial food products. Even certain cosmetics containing endocrine-disrupting chemicals can interfere with testosterone production.

“Genetically male babies might appear female externally due to testosterone disruption. Conversely, genetically female babies may develop male characteristics from excessive testosterone caused by chemical exposure,” Dr Koigi explains.

The doctor also explained that complexity increases because reproductive and urinary systems develop together, meaning intersex conditions often coincide with kidney, ureter, or urethra malformations. Statistics show that approximately one in every 1,500 live births results in an intersex child.

When confronted with intersex births, families often rush to “fix” the situation surgically. However, Dr Koigi strongly advises against hasty reconstructive surgery.

Kenya is now a continental leader in legal, medical, and educational inclusion of intersex persons

“Being intersex isn’t a disease requiring urgent treatment. Parents often raise children as either male or female, but when children grow up, they may face challenges from irreversible changes made without consent. This leads to an identity crisis and affects psychosocial development.”

The medical community has evolved significantly in its approach. Rather than assigning sex at birth in intersex cases, current best practice allows time for the child’s body to naturally align with hormones and chromosomes.

This patient approach, Dr Koigi notes, prevents the mental anguish that resulted from earlier practices where premature decisions led to identity struggles and psychological trauma.

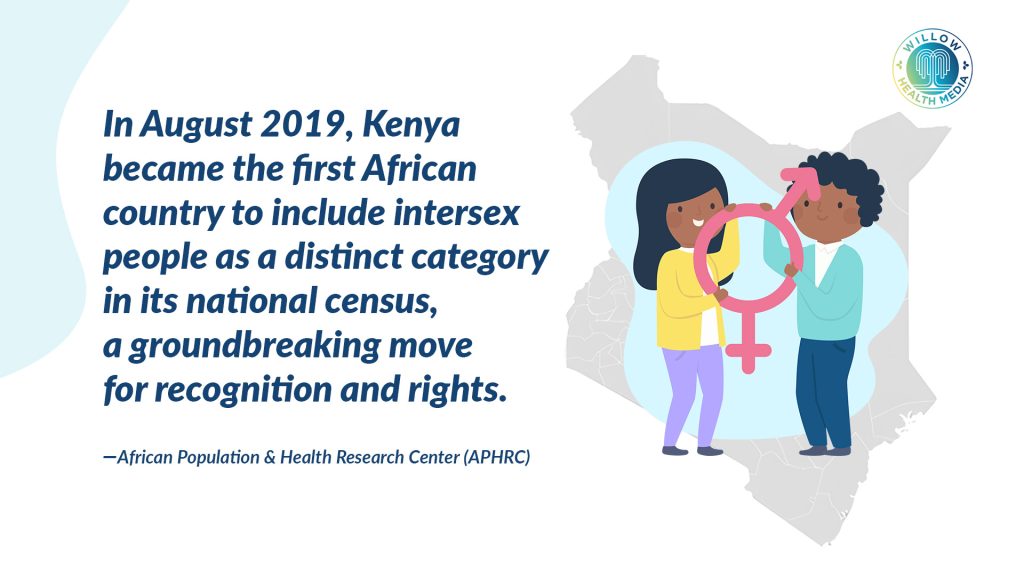

Despite the personal stories of struggle, Kenya has emerged as a continental leader in intersex inclusion since discovering its first intersex person.

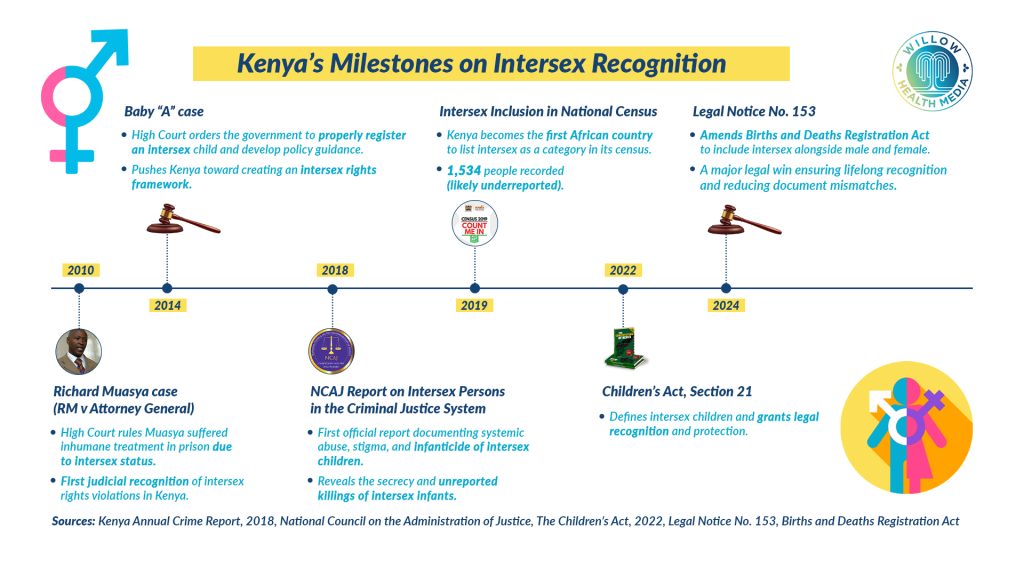

Kenya has emerged as a continental leader in intersex inclusion. This began with a landmark court case in 2010 involving Richard Muasya, an intersex prisoner born with both male and female genitalia.

The High Court ruled he had suffered inhumane and degrading treatment. A 2018 report by the National Council on the Administration of Justice confirmed that prison officers conducted strip searches driven by sadism and curiosity to expose his body to others. The court condemned these acts as cruel, humiliating, and intended to cause ridicule and contempt.

Kenya’s progress in intersex rights continued with key legal and policy milestones. In 2014, for instance, the High Court ruled in the Baby ‘A’ Case that registering a child’s sex with a “?” was unlawful. It ordered proper registration and required the government to create protective policies for intersex children.

‘Intersex’ is included in both birth and death registration certificates in Kenya

In 2018, the National Council on the Administration of Justice report acknowledged widespread stigma and intersex infanticide in Kenya despite scant statistics due to extreme family secrecy and stigma. The report cited the Kenya Annual Crime Report, whose regional survey noted many intersex infants were killed after birth: 34 in 2018, 33 in 2017 and 42 in 2016, but most cases go unreported.

Major milestones, however, include Kenya becoming the first African country to have intersex as a category in the 2019 national Census, and in 2025, the Children’s Act reinforced legal protection for intersex children with the inclusion of ‘Intersex’ in birth and death registration certificates under legal notice No.153

The country’s progress has attracted international attention, with Uganda, Ghana, and Zambia sending delegations to learn from Kenya’s legal, medical, and educational reforms supporting intersex persons.

Kenya’s legal milestones demonstrate the country’s commitment to change. These include the introduction of the Persons Deprived of Liberty Act (2014), which defines intersex status and guides authorities on handling intersex individuals in custody. Kenya’s census broke new ground by recognising intersex as a third sex category marked with ‘I’. Most recently, the Children’s Act (2022) specifically defines and protects intersex children’s rights.

Intersex persons now benefit from separate detention facilities and specific police charge sheet protections. “I was once arrested and wasn’t placed with male or female detainees, thankfully,” Gloria recalls.

I have faced discrimination because my ID, name, and face don’t match my documents

Despite remarkable progress, significant challenges remain. Intersex individuals still face substantial obstacles accessing financial services and obtaining identity documents that match their outward appearance. “I have faced accusations and discrimination because my ID, name, and face don’t match my documents,” shares Dalton. “Greater awareness is crucial to help us live normal lives,” he added.

The documentation challenges extend to birth registration and passport applications, where intersex individuals must repeatedly prove their identity due to document inconsistencies.

While Kenya has made commendable progress in supporting intersex persons, the work is far from complete. Continued efforts in public awareness, legal framework refinement, and improving access to healthcare, education, and financial services remain critical.

As Dr Koigi emphasises, the key lies in patience, understanding, and allowing individuals to develop their own sense of identity rather than imposing predetermined categories through forced surgeries. Only through such an approach can Kenya fully break the cultural barriers and medical myths that have long marginalised its intersex citizens.

Mercy Mutheu, a teacher and intersex person, lack of awareness is a major challenge. She now educates fellow teachers, arguing, “It is important for an intersex child to be fully accepted and integrated by the school for them to feel they belong and not be isolated.”

In the workplace, Gloria says, “I work at the KNCHR and I know several others in the legal sector”, and such progress for the intersex should continue “to ensure these individuals are well integrated within society.”

This is good for raising awareness. I love the unique and open coverage .