Ambitious reforms, systemic failures, and the struggle for universal coverage

When Kenya launched the Social Health Authority (SHA) on October 1, 2024, it promised a healthcare revolution.

During the announcement, the then Health Cabinet Secretary Dr Deborah M. Barasa said that the new system would replace the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF), adding that the government had allocated Sh6.1 billion as seed funding.

Speaking at a press briefing ahead of the SHA launch, in Nairobi on September 18, 2024, then Health CS Barasa unveiled SHA’s framework, declaring that the allocated Sh6.1 billion was “just a fraction of the Sh168 billion needed for full implementation”. She assured Kenyans that SHA would provide affordable, accessible, and quality healthcare services for all.

The reality has proven far more complex.

One year later, the ambitious reform presents a troubling paradox: millions registered, billions allocated, yet the healthcare system teeters on the brink of financial collapse.

At the beginning, SHA’s digital infrastructure achieved remarkable penetration. Earlier data showed the trajectory: by February 5, 2025, registration had reached 18,988,530 Kenyans, with the platform becoming one of Kenya’s most-searched terms in that period between 2024 and 2025.

However, by February 2025, only 3.1 million Kenyans had undergone means testing to determine their premium contributions. Dr Patrick Amoth, Director General for Health, warned that “without means testing, many individuals will only have access to primary healthcare and emergency services, limiting the full benefits of SHA”.

By May 2025, the government announced that SHA contributions would be deducted directly from Treasury allocations, signalling that voluntary contributions were unsustainable, a tacit admission of the contribution model’s failure.

The Ministry enabled registration via the digital portal and M-Pesa integration using Paybill 200222, providing accessible pathways for enrollment.

Health Cabinet Secretary Aden Duale later reported impressive utilisation figures: 4.5 million Kenyans accessed treatment for common illnesses and maternal care under primary healthcare, 2.2 million benefited from specialised care, including 8,000 dialysis patients and 18,000 receiving cancer treatment, with over 515,000 deliveries supported.

Geographic progress varied significantly. Speaking at the Kisumu town hall on May 13, 2025, Dr Ogolla Dorn Sunday, Director of Medical Services, reported that 46 per cent of the county’s 1.2 million residents at that time, approximately 580,000 people, had registered for SHA. He credited the scheme with bolstering primary healthcare, noting that “facilities at level two and three can now contract and expand services they previously lacked”.

Yet registration coverage remained lowest in Turkana, West Pokot, Garissa, and Samburu, perpetuating healthcare inequality in Kenya’s most marginalised regions.

The financial crisis extends beyond inadequate contributions to a systemic breakdown in provider reimbursements.

The Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Union (KMPDU) has been among SHA’s fiercest critics. In March 2025, KMPDU threatened strike action, warning that “SHA is failing Kenyans” due to chaotic payments and poor governance.

KMPDU Deputy Secretary General Dennis Miskellah stated: “When you do not pay them (healthcare providers) on time, our members in the union go without salaries”. In April 2025, KMPDU filed a formal petition to the Senate demanding comprehensive SHA insurance implementation and resolution to monthly payment lock-outs.

The Rural Private Health Association (RUPHA) facility payment survey conducted in April-May 2025 revealed the depth of the crisis. RUPHA threatened to suspend credit services to SHA patients over unpaid claims, demonstrating how provider distrust threatens the entire network’s viability.

The study revealed that only 20 per cent of Primary Healthcare (PHC)-accredited facilities received payments every month during January-March 2025, while 45 per cent received no PHC payments in that quarter. For SHIF payments, while three-quarters of Level 3-5 facilities reported some payments, 83 per cent said less than half of submitted claims had been paid, with an overall SHIF claims settlement rate averaging just 34 per cent.

Private facilities reported the lowest settlement rate at about 27 per cent, creating acute cash-flow stress. Surgical claims proved particularly problematic: over 50 per cent remained unprocessed after three months, with half of the facilities reporting surgical claims in review for 3-6 months.

The survey found that 92 per cent of facilities reported financial distress, with causes varying by level: Level 2 facilities cited unpaid PHC claims, Level 3 faced a mix of legacy NHIF arrears and PHC shortfalls, while Level 4 and 5 facilities were dominated by legacy NHIF arrears, with SHIF delays adding pressure.

SHA CEO Dr Mercy Mwangangi later acknowledged operational challenges, explaining that common reasons for claim rejection include missing forms and incomplete surgery registers, exhorting facilities to ensure submitted claims are accurate and complete.

CS Aden Duale revealed that 1,188 fraud files have been submitted to the DCI, involving forged SHA records and inflated claims, assuring Kenyans: “Investigations are ongoing to safeguard public resources. Those implicated will face justice”.

Kenyan government’s recent nationwide enforcement drive through the Kenya Gazette notice on August 29 exposed widespread non-compliance from unlicensed clinics as well as unregistered practitioners, leaving many patients at risk.

According to the notice as of late August–early September 2025, KMPDC gazetted 544 closures and 454 licence revocations in August. Additionally, the Ministry and SHA handed 1,188 files to the DCI in September.

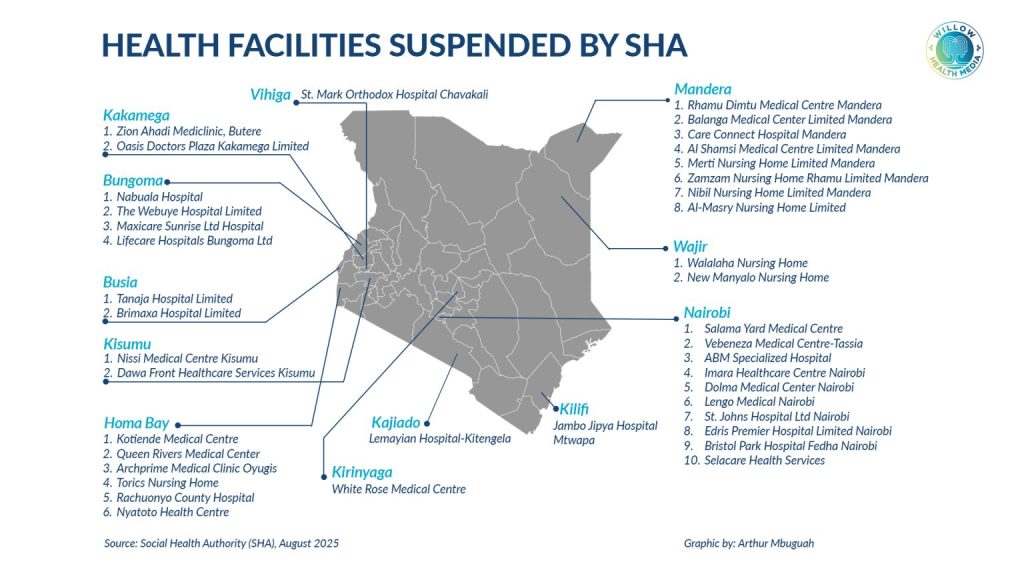

The Social Health Authority recently suspended 40 health facilities across Kenya from accessing public health insurance benefits under the Social Health Insurance Act, 2023, the largest public suspension of health providers since the transition from NHIF began.

CS Duale stated that “these facilities had engaged in corruption and theft of public resources. During the period of the investigation, these facilities are not entitled to receive any benefit from SHA. Furthermore, we will be surcharging them to recover any money already paid to them on the basis of these fraudulent claims”.

The government also identified eight doctors linked to facilities in Nairobi, Bungoma and Kilifi counties, and four clinicians linked to facilities in Nairobi and Homa Bay counties, withdrawing their user rights from the SHA portal and related digital health platforms.

Nairobi recorded the highest number of suspensions with 10 facilities, followed by Mandera with eight suspended facilities, all private.

Behind the impressive registration numbers lurks SHA’s existential threat: a catastrophic gap between those enrolled and those paying.

By August 2025, SHA had paid roughly KSh53 billion against KSh96.2 billion in claims submitted, leaving tens of billions outstanding according to RUPHA.

SHA CEO Dr Mwangangi reported that 26 million Kenyans have so far registered for the scheme.

By September, Dr Mwangangi revealed that despite 26 million registrations, only about 890,000 contributors exist in the informal sector alongside 4 million salaried contributors, meaning approximately 4.8 million Kenyans are paying into the contributory fund.

CS Duale has defended SHA’s progress while acknowledging challenges. During a recent press briefing, he reported that SHA has paid out Sh6.8 billion in primary healthcare claims, with an additional Sh1.5 billion scheduled to be paid, emphasising: “We are keen on strengthening claim processing and verification to ensure funds are utilised transparently and only valid claims are honoured”.

Duale urged timely remittance of contributions to sustain the Fund and directed patients with complaints to use the Ministry of Health’s Toll-Free Helpline (107 or 147).

On staffing concerns, Duale stated: “No staff will lose their jobs. Those not absorbed by SHA will retain their current pay and benefits when deployed to other public service roles,” while warning that “anyone found to have used fake certificates will face disqualification and legal action”.

The CS revealed he had received a report from the independent committee investigating kidney transplants and organ trafficking, calling it “a public document” that “addresses legal, ethical, and medical gaps while recommending actionable reforms”.

SHA’s first year reveals healthcare reform with noble ambitions undermined by execution failures. The scheme has achieved significant registration reach and established digital infrastructure, but faces existential threats from inadequate contributions, provider payment chaos, fraud, and systemic governance gaps.

The RUPHA survey recommends immediate actions, including publishing a weekly reconciliation dashboard for PHC and SHIF flows, fast-tracking surgical claims with a dedicated verification lane and 60-day processing target, and activating short-term liquidity support for facilities with claims in verified review.

Medium-term reforms should reconcile and clear legacy NHIF arrears with a published timetable, automate claim adjudication and remittance statements, and create an independent provider grievance cell with binding timelines.