The health budget goes to paying salaries and running costs, leaving little money for hospitals, medicines or machines.

Healthcare is a fundamental human right and a cornerstone of national development. The Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) 2025 Economic Survey offers critical insights into the nation’s healthcare sector, highlighting achievements and significant challenges that require urgent attention. This analysis unpacks the survey’s findings on health and proposes potential solutions.

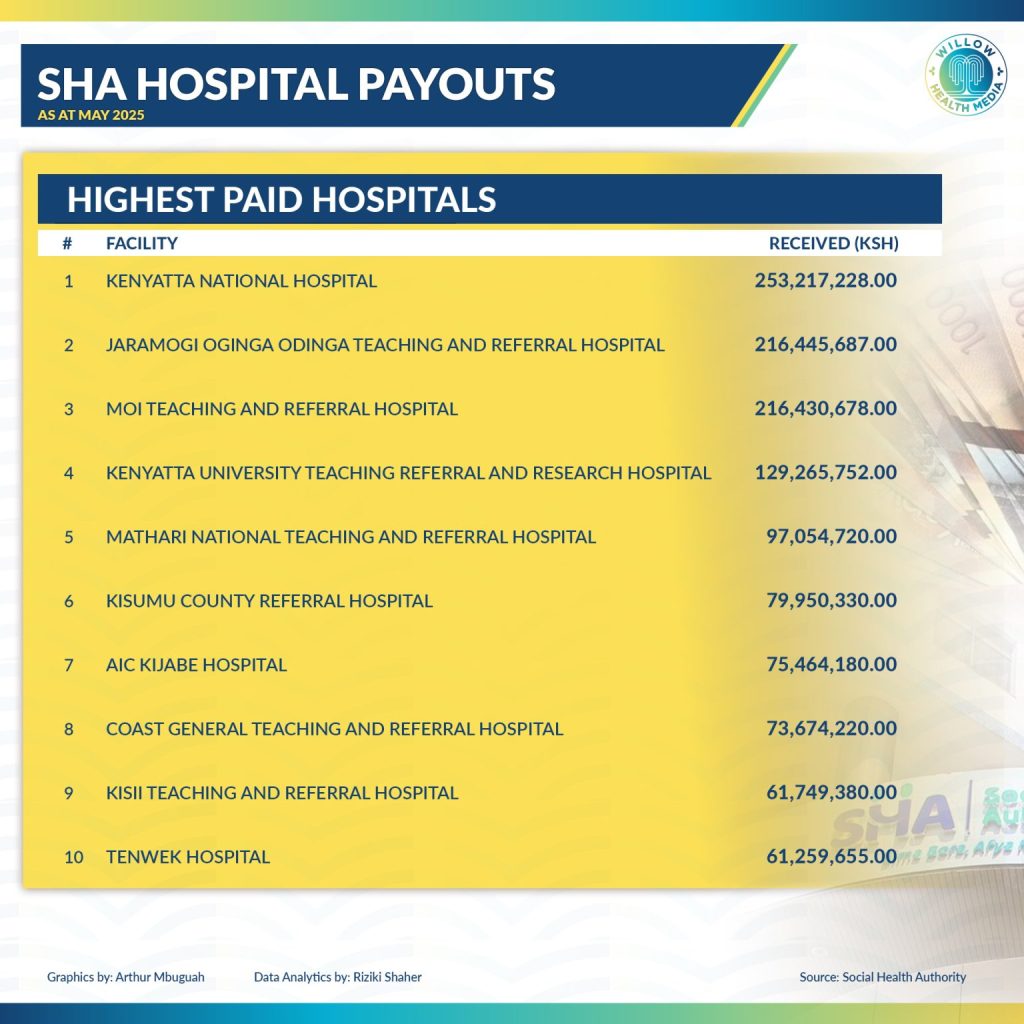

The 2025 Economic Survey reveals a mixed picture of Kenya’s health financing. While the government is spending more money on health, serious problems remain, especially with the new Social Health Authority (SHA).

Kenya’s health spending is increasing each year, but it’s still not enough. The national government plans to spend about Ksh232 billion on health this year, up from Ksh193 billion last year. County governments will add another Ksh124 billion. While these numbers sound large, they represent only about six per cent of the total government budget.

This falls far short of what African leaders promised in the Abuja Declaration – that countries should spend 15 per cent of their budget on health. Kenya is missing this target by over nine per cent, meaning healthcare remains underfunded. Making matters worse, most of the health budget goes to paying salaries and running costs, leaving little money for building new facilities or buying equipment.

The Social Health Authority (SHA) represents Kenya’s ambitious attempt to provide healthcare for all citizens, but its launch faces serious challenges. The biggest problem is that the old insurance system (NHIF) owes healthcare providers Ksh24 billion- a massive debt that SHA must somehow handle.

SHA has three main funding sources. Two are funded by taxes, but the largest one depends on contributions from citizens, especially those in informal jobs like small traders and farmers. Getting these workers to pay into the system has proven difficult – the old NHIF only managed to enroll 27 per cent of informal workers. Many people can’t afford the contributions or don’t see the value in paying for health insurance.

There are also concerns that people might end up paying more out of their own pockets for healthcare under the new system, especially for specialized treatments. Solutions to fixing Kenya’s Health Financing would include the following:

- Increase Health Budget:

- Ramp up health spending to hit the 15% Abuja target

- Smart private partnerships – but keep public healthcare affordable

- Fix SHA Problems

- Clear the Ksh24 billion NHIF debt immediately

- Lock in stable government funding for critical care funds

- Launch hard-hitting public awareness campaigns

- Bring Informal Workers Onboard

- Tailor affordable payment plans for casual earners

- Build trust through transparent SHA operations

- Eliminate hidden costs with full coverage for basic care

Bottom line is have more cash, cleaner systems, and smarter enrollment to save Kenya’s healthcare overhaul.

The survey reveals significant problems with Kenya’s health infrastructure – the buildings, equipment, and systems that make healthcare possible.

Kenya now has nearly 16,000 health facilities, with most growth happening in mid-level facilities. However, over half of all facilities are privately owned, while public facilities lag behind. When it comes to hospital beds, 97 per cent of the new beds added were in private facilities, raising concerns about whether poor people can access quality care.

The distribution of facilities is also unfair. Most are concentrated in cities and towns, leaving rural communities with limited access to healthcare. This geographic inequality makes it harder to achieve universal health coverage.

Most concerning is that facilities are poorly equipped and understaffed. Only seven per cent of facilities are ready to provide basic outpatient services, and just two per cent can offer all essential health services. This means many facilities exist on paper but can’t actually help patients effectively. The solutions to building better healthcare infrastructure include the following:

- Smart Public Investment: Focus on upgrading mid-level facilities in underserved areas so they can provide essential health services.

- Fair Distribution: Use mapping technology and needs assessments to ensure new facilities are built where they’re most needed.

- Better Equipment and Supplies: Invest in essential medical equipment and create reliable supply chains, especially for primary healthcare facilities.

- Smart Partnerships: Develop clear rules for working with private companies on health infrastructure while keeping public health as the priority.

The survey highlights ongoing challenges in maternal, child, and adolescent health. Ensuring safe childbirth remains a major challenge. Fewer women are giving birth in health facilities – a worrying trend that reverses previous progress. About 1.2 million women delivered in health facilities in 2024, but this represents a decrease over five years.

Cesarean sections now account for 18 percent of all deliveries. While the World Health Organization suggests 10-15 percent as ideal, some research indicates up to 19 percent might be appropriate. Kenya’s rate needs careful monitoring to ensure surgeries are medically necessary, not driven by financial incentives.

Barriers preventing women from accessing skilled birth care include cost, distance to facilities, poor quality of care, and cultural beliefs about childbirth. The solutions to ensuring safe childbirth would comprise:

- Improve Maternity Services: Implement national standards for maternal care and strengthen emergency referral systems.

- Remove Barriers: Address cost barriers beyond just free services – help with transport costs and provide health education to address cultural concerns.

- Appropriate Surgery Rates: Follow international guidelines for cesarean sections and adjust insurance payments to avoid unnecessary surgeries.

- Better Training: Invest in training for maternal health staff and strengthen systems to investigate maternal deaths.

While teenage pregnancy rates have dropped nationally from 18 percent to 15 percent, huge regional differences remain. Some counties like Samburu have rates as high as 50 percent, while others are much lower.

This problem is closely linked to poverty and lack of education. Recent policy changes requiring parental consent for reproductive health services may actually make it harder for teenagers to get help.

The solutions to supporting young people would comprise:

- Multi-Sector Approach: Keep girls in school, provide comprehensive sex education, and address poverty through economic programs.

- Youth-Friendly Services: Expand accessible, confidential health services specifically designed for young people.

- Better Policies: Advocate for evidence-based policies on adolescent reproductive health and improve coordination between different agencies.

The availability and distribution of healthcare workers are fundamental to system effectiveness. Kenya faces a serious shortage of healthcare workers.

The country has about 30 doctors, nurses, and clinical officers for every 10,000 people, well below the WHO recommendation of 45 per 10,000.

Put simply, Kenya has one doctor for every 5,263 people (WHO recommends one for every 1,000 people) and far fewer nurses than recommended.

The country has about 14,000 doctors and dentists, 75,000 registered nurses, and 31,000 clinical officers serving a population of over 52 million people.

These numbers clearly show the shortage, and the situation is worse in rural areas where many specialists are unwilling to work. Th solutions to valuing healthcare workers includes:

- Comprehensive Strategy: Align training programs with population needs, improve working conditions, and create incentives to keep healthcare workers from leaving the country.

- Better Coordination: Clarify roles between national and county governments in managing healthcare workers.

- Community Health Workers: Create official policies for community health volunteers and integrate them into primary healthcare teams.

- Specialist Training: Expand specialist training based on actual needs and develop strategies to ensure specialists serve in all counties.

- Better Data: Create a robust system to track healthcare worker numbers and distribution.

The 2025 Economic Survey shows a Kenyan healthcare system at a critical point. While some progress has been made, significant gaps remain that demand urgent, comprehensive action.

Success will require sustained political commitment, increased and well-managed public investment, robust strategic planning, and strong accountability systems.

The path forward is clear: increase health funding, fix the new insurance system, build and equip facilities where they’re needed most, train and retain more healthcare workers, and ensure that mothers, children, and adolescents receive the care they deserve. Only through coordinated action across all these areas can Kenya achieve its goal of healthcare for all citizens.

Dr Dennis Okaka is a Health Strategy Consultant.