Older children and adolescents remain “a forgotten crisis” due to premature mortality, with the report showing they are experiencing hopelessness for the future, weighted down by anxiety and depression

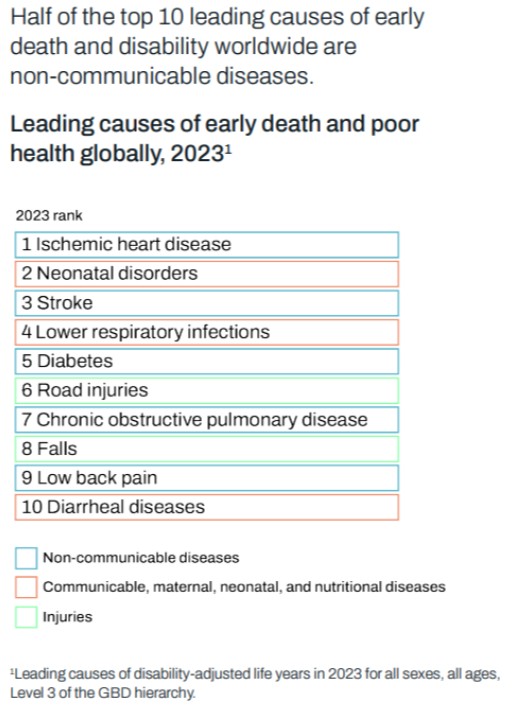

The world’s leading causes of death have shifted dramatically from infectious to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) over the past three decades, according to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2023 study launched at the ongoing World Health Summit in Berlin.

The landmark report, spanning 17,000 researchers across 167 countries, marks a decisive moment for global health. In 1990, communicable, maternal, and neonatal conditions dominated the global disease map.

By 2023, those “causes of poverty,” as GBD Director Dr Christopher Murray described them, had declined sharply, while diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancers, and mental disorders surged to the top.

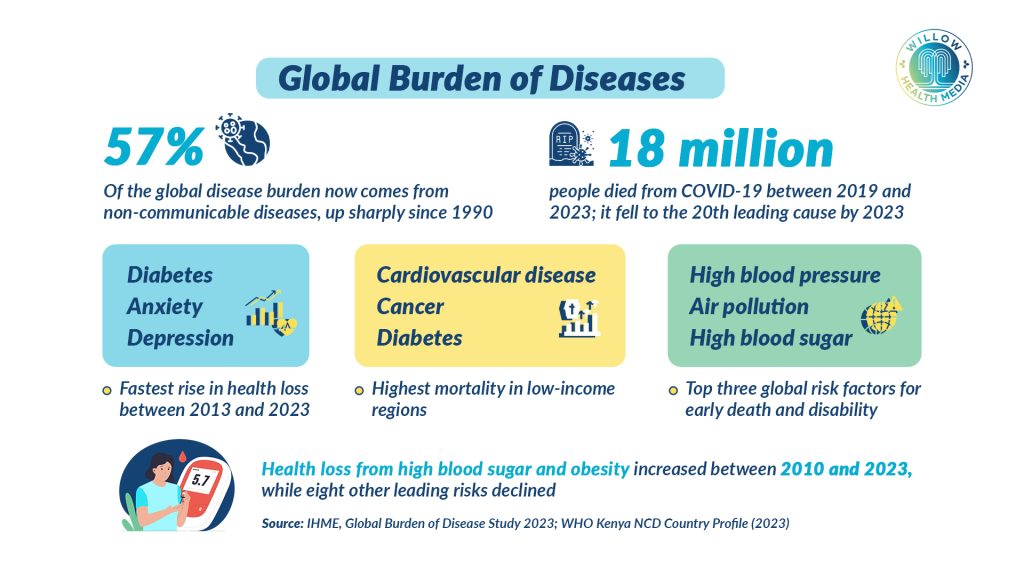

“This is a huge shift globally towards non-communicable disease,” said Murray, noting the steepest rise in low- and middle-income countries, where NCDs now account for 57 per cent of total disease burden. While global life expectancy has rebounded after the Covid-19 pandemic, vast inequalities persist, from 55 years in the Central African Republic to 85 years in Singapore.

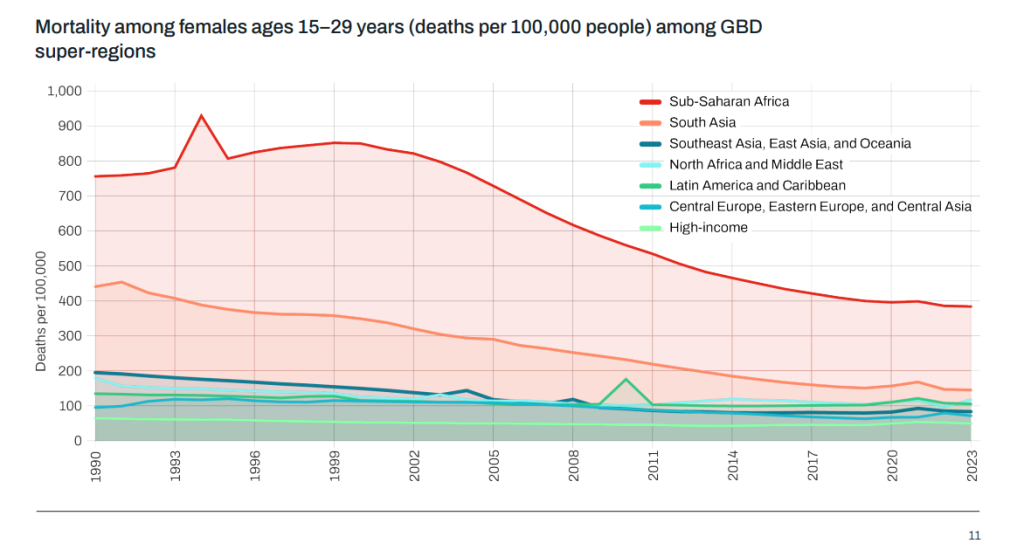

The report shows mixed progress across Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa has made major gains in child survival and infectious disease control, but still bears the highest rates of premature death and disability.

New data reveal that female mortality among young women (15–29) in the region is 61 per cent higher than earlier estimates. Despite progress against child deaths, older children and adolescents remain “a forgotten crisis,” warned Dr Zulfiqar Bhutta of Aga Khan University.

According to Dr Alarcos Cieza, Unit Head for Sensory Functions, Disability and Rehabilitation at the World Health Organization (WHO), one in three deaths before age 70 is due to cardiovascular, respiratory, cancer, diabetes, or kidney diseases.

“We are talking about 17 million premature deaths every year,” she said, roughly the same number of deaths caused by Covid-19 over three years. “In sub-Saharan Africa, one in two premature deaths is due to NCDs; in South Asia, it’s two in three. Women in these low-income areas are dying earlier than men due to those conditions.”

Dr Cieza stressed that the burden extends beyond deaths. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) capture “the years people spend living with the consequences of these conditions in poor health,” underscoring the need for continuous management of chronic diseases.

High blood pressure remains the number one NCD risk factor, while obesity and blood sugar are rising steeply. “The transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases is happening in an accelerated manner in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia,” said Dr Cieza.

While eight of the top 10 global risk factors declined between 2010 and 2023, health loss from high blood sugar and body mass index rose sharply; evidence that progress against infectious diseases is being offset by lifestyle-related epidemics.

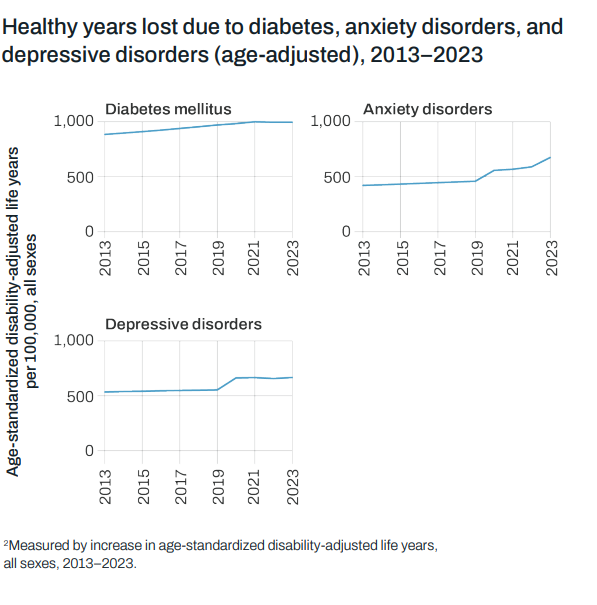

“The burden of diabetes alone has grown by more than 25 per cent in the past decade,” she noted, alongside rising depressive and anxiety disorders.

Life expectancy has been reduced due to climate change, historical exploitation and weak governance

At the summit, Professor Ibrahim Abubakar of University College London warned that global health efforts remain unequal. “If you define global health as something to do with inequalities and you haven’t done anything about the Sahel, then you’re probably not doing global health,” he said.

Life expectancy in parts of the Sahel remains 30 years shorter than in high-income nations, with preventable deaths from malaria, pneumonia, and malnutrition still common. Abubakar linked the crisis to climate change, historical exploitation, and weak governance, urging leaders to recognise the Sahel as a test of collective responsibility.

The GBD 2023 report exposes a trio of “silent epidemics”: mental health disorders, obesity, and violence. Dr Damian Santomauro of the Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research said the peak burden of mental disorders now falls among 15 to 19-year-olds. Since 2010, adolescent anxiety has risen 70 per cent and depression 30 per cent, driven by social isolation, economic insecurity, and “climate despair.”

“This generation is experiencing hopelessness for the future,” he warned. Globally, fewer than 10 per cent of people with major depression receive adequate treatment, and in Africa, the proportion is far lower.

Dr Emmanuela Gakidou, Co-Founder of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), highlighted that violence against women and children is now a top-five global health risk for women aged 15-49.

“You can no longer talk about maternal and reproductive health without addressing violence,” she said. One in three women faces intimate partner violence, and one in five girls experiences sexual abuse before adulthood, experiences that increase the risk of chronic diseases, including diabetes and asthma.

Environmental dangers compound these challenges. The GBD 2023 report attributes 7.5 million deaths to air pollution and 3.5 million to lead exposure last year. Heat-related deaths have more than doubled since 1990, from 250,000 to 550,000.

“We are only at the start of the global heat-health emergency,” warned Professor Michael Brauer. For Africa, where air conditioning remains out of reach for most households, the consequences could be catastrophic.

These environmental pressures converge with rising metabolic risks such as high blood pressure, obesity, and elevated blood sugar, forming what the report calls a “dual challenge”: the unfinished fight against infectious diseases alongside an accelerating wave of chronic and environmental illness.

Chile’s Health Minister, Dr Ximena Aguilera, presented her country as a model for lower-income nations. Chile’s Explicit Health Guarantees Scheme, built on GBD data, ensures timely access, quality care, and financial protection for 90 priority conditions, 80 per cent of them NCDs.

Suicide rates rose 58 per cent between 2017 and 2023, yet mental health spending remains below one per cent of the national health budget

“Strong primary healthcare and intersectoral collaboration can protect populations from both epidemics and economic shocks,” Aguilera said, emphasising local “territorial” health models addressing climate, mental health, and nutrition.

In Africa, data gaps threaten progress. Dr Irene Agyepong of Ghana’s College of Physicians and Surgeons argued that “it’s hard to ruin a health system by getting better data.” With donor-funded surveys like the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) ending, she urged countries to invest in domestic health data systems.

The GBD study drew on 24,000 African data sources but still found major gaps in mortality reporting. Without reliable local data, warned Bhutta, policymakers remain “blind to what the mind does not know.”

Kenya reflects these shifts. Life expectancy has risen to 67 years, yet inequality persists between counties. According to IHME’s 2023 country profile and the Kenya STEPwise NCD survey, NCDs now cause 55 per cent of all deaths.

Hypertension affects one in four adults, but only half are aware of their status. Diabetes has doubled in 20 years, and 30 per cent of urban women are overweight or obese. Air pollution ranks among Kenya’s top five risk factors, driven by traffic emissions and household fuels.

Mental health disorders, particularly depression and substance use among youth, are surging. Suicide rates rose 58 per cent between 2017 and 2023, yet mental health spending remains below one per cent of the national health budget.

The new Social Health Authority (SHA) promises broader coverage, but overall health financing still lags below the 15 per cent Abuja target. “Every country has the capacity to do more,” Bhutta urged. “The first and foremost thing that would make a difference is domestic financing for health.”

Richard Horton, Editor-in-Chief of The Lancet, lamented that global health has become “fragmented and bloated.”

“We had eight Millennium Development Goals, then 17 Sustainable Development Goals with 169 targets. What’s next, 300?” he asked.

Horton called for integration, aligning food, climate, gender, and health policies under a framework of “recognitional justice”, ensuring fairness in both resources and power. “The GBD is the most powerful mechanism for independent accountability in health today,” he added.

The GBD 2023 findings offer African policymakers a clear roadmap: shift from crisis response to prevention and continuity of care. Health systems must adapt to lifelong conditions like hypertension and diabetes through community health networks, steady medicine supply, and trained staff.

With donor funding declining, governments must expand national health budgets and spend more efficiently, prioritising programs for women and youth. Mental health and gender-based violence must move to the centre of public health strategies.

As WHO Chief Scientist Dr Jeremy Farrar concluded: “There is a world of opportunity in the GBD. We need to have hope, not despair. And we need to work together.”