Married couples suffering from bipolar disorder sometimes engage in sexual infidelity due to an inflated sense of self-importance and impulsivity- Elizabeth Mutuku, psychologist

By Yvonne Kawira

Samuel Ochieng, now a lawyer, was a budding gospel artist in 2000 when he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder- which has no cure. It is only managed through medication and therapy.

Ochieng, then known as Gospel Dynamite, was 18. He had energy. Clocking five concerts a day was no big deal. But intense schedules, blended with overzealous religious fervour triggered psychotic episodes: delusions of grandeur, fast-paced thoughts, belief he was a prophet, such.

His mother and brother noticed the changes and sought medical intervention. But three years earlier, his family mistook his erratic mood swings for the motions of adolescence. They were wrong.

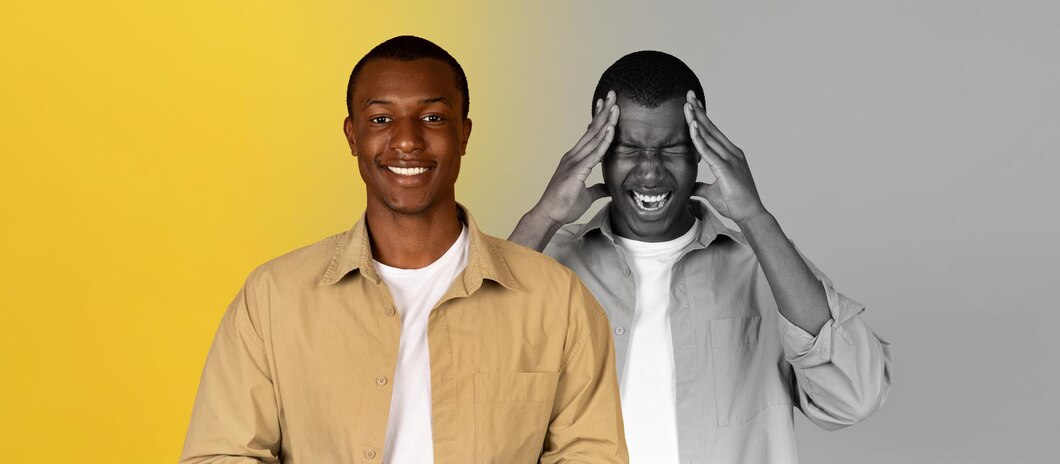

A psychiatrist diagnosed Ochieng with bipolar I disorder characterised by manic highs to depressive lows. During manic phases, four hours of sleep were enough. He also engaged in impulsive spending sprees, and felt invincible. His mind flooded with new ideas “like I have superpowers” only to later suffer financial woes, damaged relationships, and exhaustion.

Depressive episodes resulted in 10-plus hours of sleep and “I did not brush my teeth or shower. I loathe myself.” Suicidal thoughts clouded his mind, impacting his work.

The diagnosis, however, forced Ochieng to confront a mental illness requiring lifelong management. “I initially felt deficient,” with side effects of the medication leading to weight gain and constant drowsiness, affecting self-esteem.

Ochieng fought stigma too. He was labelled “mad” in college. Others blamed demons and witchcraft, but discipline and resilience worked wonders. “I exercise regularly, go to bed at the same time, and never miss medication.”

Regular psychiatrist visits ensure treatment balances efficacy with side effects. Support groups “help me cope with my episodes besides tips on the best medications” while family recognise early signs for medical help before manic mood swings escalate.

Despite the challenges and a psychiatrist advising against returning to law school, Ochieng passed the bar in 2015, and is now an advocate of the High Court of Kenya. He also founded Serene Minds via which he hosts mental wellness concerts where individuals share experiences and psychologists offer guidance.

He also uses his social media pages for insights into bipolar disorder, explaining it is a chemical imbalance in the brain—no more a moral failing than diabetes or cancer.

Ochieng also advocates for government subsidies for medications and improvements in the conditions of psychiatric wards to make them more therapeutic.

Other Kenyans who have publicly spoken about bipolar disorder include former Nairobi Woman Rep. Rachel Shebesh in 2021. Her hubby had identified the condition in 2006 though. Debilitating episodes of depression led to suicidal thoughts, affecting family relations, but Shebesh has been on medication and therapy since.

According to psychologist Elizabeth Mutuku “bipolar disorder can often be mischaracterised, leading to stigma and misunderstanding” as it has overlapping similarities with other conditions, like Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). “Both disorders can present with high energy levels and rapid speech, making accurate diagnosis essential,” says Mutuku.

Bipolar I disorder has at least one manic episode lasting a week or so when “individuals experience a surge of energy, increased productivity, rapid speech, and a reduced need for sleep. They can appear euphoric and may even engage in risky behaviours.”

It is not uncommon for married couples suffering from bipolar disorder to engage in sexual infidelity due to their inflated sense of self-importance and impulsivity.

In contrast, Bipolar II Disorder features major depressive episodes lasting at least two weeks, besides one hypomanic episode lasting four days. ”While individuals with Bipolar II may not experience the same level of mania, their depressive episodes can be equally debilitating,” notes Mutuku.

Symptoms of bipolar disorder emerge at around 18 years for Bipolar I and late adolescence or early adulthood for Bipolar II. ”Early intervention is crucial,” cautions Mutuku. “The longer we wait to treat, the more challenging it becomes.”

As bipolar disorder has no cure “medications like mood stabilisers and antipsychotics are pivotal in managing symptoms. Antidepressants may also be prescribed during depressive episodes,” she says, adding that Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) is the last resort for those unresponsive to medication.”

A holistic approach is crucial as “medication alone is not enough. We need to incorporate psychotherapy, family therapy and counselling for a supportive environment,” she advises, adding that lifestyle changes play a vital role like “avoiding psychoactive substances, managing stress, and implementing coping strategies.”

Mental healthcare in Kenya faces myriad challenges, according to Counselling psychologist Fidelma Mbithe who cites lack of accessible mental health services and facilities, entrenched societal stigma to severe shortages in trained personnel.

Kenya has about 3,956 government-owned health facilities, including 284 Level 4 hospitals- of which only 29 offer mental health care services, a mere 0.7 per cent of total facilities, according to the Kenya Economic Survey 2023. Additionally, psychiatric units are in 15 of the 47 counties and patients in the other 32 counties are forced to travel to Mathari National Teaching and Referral Hospital (MNTRH) in Nairobi for treatment.

“Mental health conditions among civil servants saw cases increasing from 5,000 to around 30,000,” Mutuku shares, underscoring the urgent need for better mental health resources and education.

Mbithe also laments that “mental health services are expensive and out of reach for low-income communities” with one saving grace being the Mental Wellness Benefit Package under the Social Health Insurance Act.

The package covers mental health education and counselling, screening, management, and referral for behavioural, neurodevelopmental, affective and psychoactive disorders. It also provides rehabilitation services for substance-related addictive disorders.

Access is offered at Levels 3 to 6 hospitals at Ksh1,200 per visit for outpatient under a fixed-fee-for-service system. Inpatient services at Levels 4 and 5 hospitals cost Ksh3,500 and Ksh5,000 at Level 6.

For substance abuse rehab and detoxification costs Ksh14,000, while the full rehab is priced at Ksh125,000, charged on a case-based system.

Access rules specify a limit of seven outpatient visits for paid-up SHA members. Mental illness services are assessed through SHIF and ECCI funds, with a maximum inpatient limit of 35 days for behavioural disorder management.

Admissions for rehab must be pre-authorized, and if beneficiaries do not complete the program or stay at least 45 days, SHA reimburses Ksh1,000 for each day not attended, up to a maximum of 10 days.

Money aside, Mbithe singles out ignorance, misconceptions and limited mental health literacy as “significant barriers” to recognising symptoms and understanding treatment options. “Many people don’t understand mental health issues are treatable,” adds Mbithe listing the youth, the elderly, prisoners, the disciplined forces, and the boy child as most vulnerable.

Cultural beliefs and religion pose another challenge as “bipolar disorder is often seen as a curse, bewitchment or result of sin, complicating treatment acceptance,” explains Mbithe.

In children, bipolar disorder is sometimes mistaken for its variant, Cyclothymic Disorder, which features periods of hypomanic and depressive symptoms that do not meet the criteria for hypomanic or major depressive episodes. ”For children, symptoms must persist for at least one year for a diagnosis and two years for adults,” says Mutuku, making cyclothymic disorder challenging to identify and manage.

In Kenya, mental illness accounts for about 13 per cent of the total disease burden and costs around Kshs62.2 billion annually, or 0.6 per cent of the GDP. Additionally, out-of-pocket health expenditures account for 27 per cent of total spending, exceeding the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation, according to the 2020 Taskforce on Mental Health, which pegs the mental health sector’s budget at a mere 0.01 per cent of the national health budget.

According to ‘Kenya Adolescent Mental Health Group’, a report released this January by The Lancet, there is a significant disparity in access to mental health services between Nairobi and other regions, suggesting mental health issues might be underreported outside urban areas.

The report notes that Kenya has only 150 psychiatrists or one psychiatrist per million people – most of them based in Nairobi- meaning people in rural or less urbanized areas are unlikely to receive proper diagnosis or treatment.

Most neurologists are based in urban areas (Nairobi, Kisumu, and Mombasa), creating an urban bias where those in cities are more likely to seek and receive mental health care- and thus have higher reported cases. This could, in turn, mean that actual prevalence may be more evenly distributed, with rural areas lacking documentation due to fewer resources and greater stigma.

Neurologists are primarily available in private settings, limiting accessibility for lower-income individuals. This forces people in rural areas to rely on primary healthcare providers who may lack specialized mental health training, leading to underdiagnosis or mismanagement of complex conditions like bipolar disorder.

Mbithe calls for an increase in the number of skilled mental health personnel, the full implementation of Universal Health Coverage that ensures access to mental health services regardless of gender, age, location, or social class.

Mental health interventions should be “organized around individuals’ legitimate needs and expectations,” she says, adding that a national anti-stigma campaign, leveraging public forums, sports, media, art, and cultural festivals is crucial.

To reduce stigma and promote social integration, Mbithe suggests “people with mental health conditions have similar opportunities to develop skills, pursue education and gain employment” through a Mental Health Action Plan and legal reform “to decriminalize suicide and symptoms of mental illness.”