Thanks to support from Gavi, more parents are celebrating their children’s 5th birthdays, a milestone that was once out of reach for many. Vaccines are doing more than preventing disease; they’re giving families hope, and the precious gift of time together

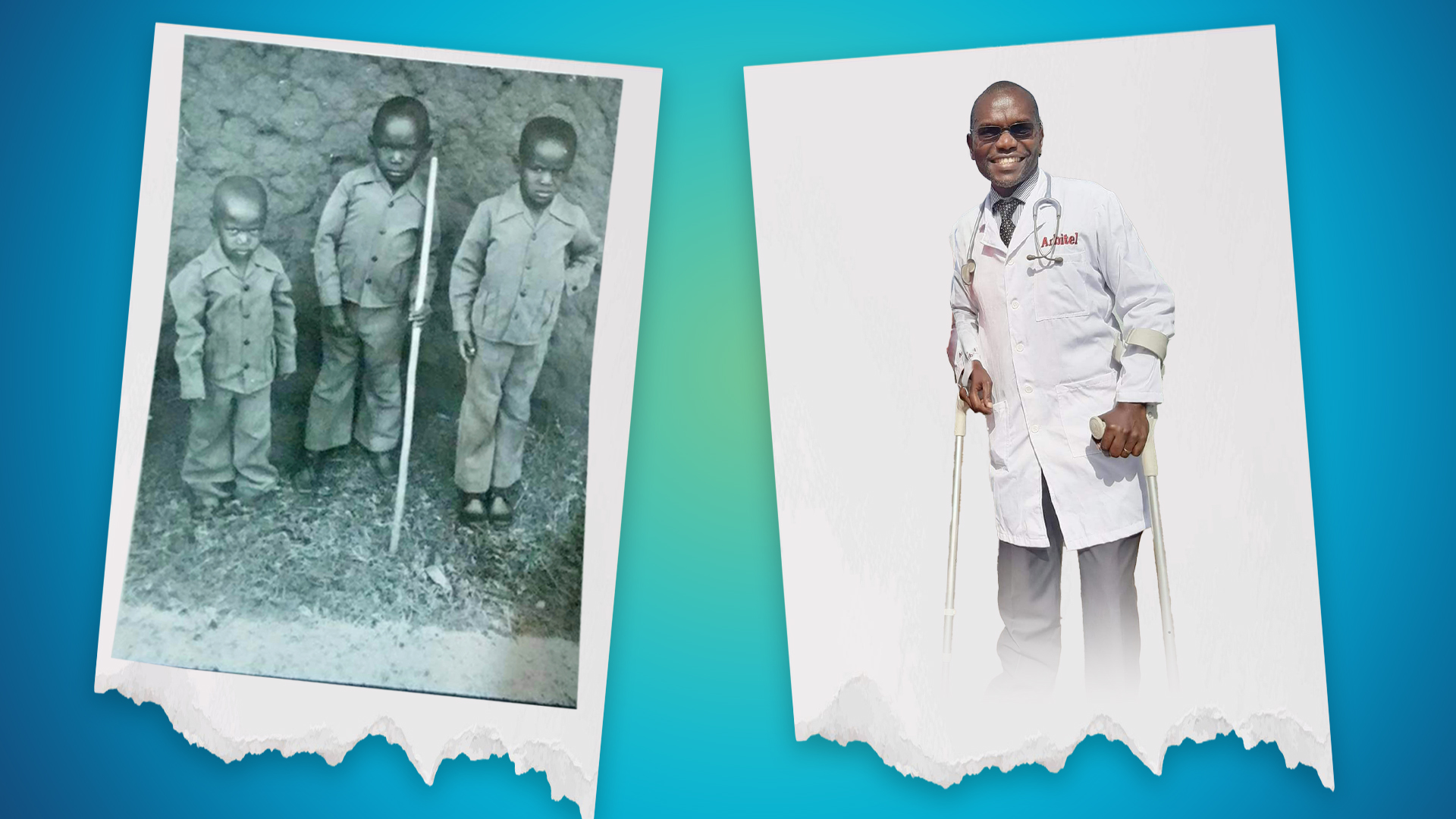

Dr Riro Mwita, a Physician at Kiambu Level 5 Hospital, knows well the value of a vaccine. Mwita was born a normal child over four decades ago. However, he was not fortunate to get vaccinated against poliomyelitis, a highly infectious disease caused by the poliovirus, that primarily affects the nervous system, leading to permanent disability, paralysis and even death.

At one year old, the disease struck him, leaving him first with paralysis, then with a permanent disability. Nonetheless, Mwita beat the odds, going on to become a celebrated physician, family man and champion for vaccines and for the inclusion of people with disabilities.

One of Dr Mwita’s rallying cries is for parents to ensure their children get vaccines on time to protect them against vaccine-preventable diseases. He could have escaped the polio curse were it not for limited vaccine access, low awareness, and a lack of global commitment to enhancing vaccine access over the past five decades.

While the 1970s marked a turning point in recognising the need for polio control, it wasn’t until the late 1980s that the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was established, with a more focused global effort to eliminate polio.

Gavi’s introduction of PCV in 2011 made Kenya the first African country to roll out the crucial vaccine that fights against pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis

Notably, in 1980, the Kenya Expanded Programme on Immunisation (KEPI) was established to coordinate immunisation services targeting six childhood killer diseases, namely tuberculosis (TB), polio, whooping cough, diphtheria, tetanus and measles, through its infant immunisation program.

And while KEPI was able to bridge the vaccination gap and enable access for children to vaccines, coverage was relatively low, with regional disparities and challenges in reaching remote areas. According to the Kenya 2003 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), only 57 per cent of Kenyan children aged 12-23 months had received the full recommended vaccine regimen.

This changed in 2003 with the entry of Kenya into Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, a public-private partnership that works to increase access to new and underused vaccines for children in the world’s poorest countries. Since then, Gavi has helped Kenya make strides in its immunisation goals, increasing overall coverage from 70 per cent in 2000 to 90 per cent in 2024.

Moreover, Kenya, with the support of Gavi, has managed to broaden its range of vaccines from the standard four vaccines recommended for children between 12-23 months, namely BCG for tuberculosis, DPT for diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus, as well as polio and measles vaccines.

This was replaced in 2001 with Kenya’s introduction of a Pentavalent vaccine, which protects against five major childhood diseases, including the initial four, in addition to Hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib).

Gavi also introduced the Yellow Fever vaccine into its schedule in four districts in Kenya in 2002, followed by the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) in 2011, making Kenya the first African country to roll out the vaccine that protects against pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis.

2014 saw the introduction of the Rotavirus vaccine, followed by the second Measles-Rubella vaccine (MR2) and the Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV) in 2015. Gavi introduced the Meningococcal A (MenA) vaccine to its schedule in 2018, and lastly, the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in 2019.

The impact of Gavi support is evident in minimised disease outbreaks, lower mortality

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

The first Pentavalent vaccine (DTP/HepB/Hib) was introduced in 2002 to protect against the three major childhood diseases of diphtheria, pertussis (whooping cough) and tetanus, in addition to Hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenza b, a major cause of meningitis and pneumonia.

According to the World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund National Immunisation Coverage (WUENIC) data, Pentavalent vaccine coverage increased from five per cent in 2001 to 92 per cent in 2018, an 87 per cent overall increase. This sharp increase marked a significant reduction in Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infections by over 90 per cent.

For instance, in Kilifi (district) between 2000-2014, Hib infections reduced dramatically from 62.5 to 4.5 cases per 100,000, a 93 per cent decrease. This was due to the increase in Pentavalent vaccine coverage from 5 per cent to 92 per cent in the same period, an 87 per cent increase.

Yellow Fever

Before 2001, Yellow Fever was sporadic and largely undetected in Kenya. However, there were outbreaks recorded in 1995, 2011, 2016 and 2022. Between 1992-1993, Kenya recorded 55 cases of haemorrhagic fever, of which 26 were confirmed to be Yellow Fever. This was before Gavi began Yellow Fever vaccine support for Kenya in 2002.

Since 2002, there have been fewer outbreaks as Gavi supports vaccination campaigns and active disease surveillance strengthening. Through Gavi support, Kenya has also improved case detection and specialised sample testing at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and WHO laboratories.

Kenya is also part of the Eliminate Yellow Fever Epidemics (EYE) strategy launched in 2017 by WHO, Gavi, and UNICEF, through which it has strengthened national planning, risk assessment and vaccine readiness.

Notably, WHO and Gavi helped Kenya respond to a 2011 outbreak in the Rift Valley through the International Coordinating Group (ICG) on Vaccine Provision. And during the 2022 outbreak in Isiolo, vaccines from the Gavi-funded global Yellow Fever stockpile were deployed for emergency immunisation.

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is the most common cause of vaccine-preventable severe acute gastroenteritis (AGE) among infants and young children worldwide, with the main symptoms being loose stool and frequent unexplained vomiting.

Before 2014, rotavirus was a major cause of child hospitalisations and deaths in Kenya, causing a substantial healthcare burden. According to a research article by Richard Omore, Sammy Khagayi and others on the rates of death and hospitalisation from rotavirus between 2010 and 2014 in Kenya, there were 429 hospitalisations and 45 deaths per 100,000 deaths in children under five years.

The 2014 introduction of the Rotavirus 1 (RV1) vaccine in Kenya, with the support of Gavi, led to dramatic declines in rotavirus hospitalisations of up to 82 per cent in some rural regions within two years. The proportion of diarrhoea in children due to rotavirus fell from around 38–39 per cent to roughly 14–15 per cent, demonstrating the strong impact of the vaccine.

Two demographic surveillance sites (Kilifi and Siaya) recorded dramatic reductions of 57–59 per cent in the first year, and 80–82 per cent by the second year post-introduction.

In Western Kenya (Kisumu), rotavirus vaccine introduction was also tied to a 44 per cent drop in all-cause child mortality among vaccinated kids, and a 34 per cent reduction in diarrhoea incidence.

Rubella and Measles

Gavi introduced the second Measles-Rubella (MR2) vaccine in 2015, when there were 422 reported cases of rubella in Kenya. The vaccine was distributed through a nationwide Supplementary Immunisation Activity (SIA) in 2016, targeting nearly 20 million children aged 9 months to 14 years, after which the MR2 vaccine was added to the routine childhood immunisation schedule, replacing the standalone measles vaccine across all 47 counties.

Since its introduction in 2015, the cases reduced steadily to a low of 66 in 2023. However, there was an abnormal spike in cases in 2024, which recorded 363 cases. The spike was attributed to Covid-19 pandemic disruptions, the ensuing reduced surveillance, and the sudden resumption of activities post-Covid, which also saw a resumption of enhanced disease surveillance.

Similarly, measles saw a decline from 21,002 cases in 2000, down to 20 cases in 2004 when the first measles vaccine was introduced into the immunisation schedule. However, there were spikes in different years as Kenya was relying on mass vaccination campaigns as opposed to routine immunisation. The incidence dropped to 95 cases after the second measles-rubella vaccine was reintroduced in 2015, up until 2022 when there was a sharp spike to 1,774 cases attributed to Covid-19 pandemic disruptions.

As of last year, there were 525 reported cases of measles in Kenya, but Gavi has made strides in providing disease surveillance support as well as vaccine resources to keep the numbers at a manageable level.

Every dollar invested saves healthcare costs, yields billions in health and economic gains

Since 2001, Gavi has supported Kenya’s vaccination programs to the tune of US$940 million (about Ksh121.4 billion).

In 2008, Gavi introduced a co-financing policy whereby countries applying for vaccine support are required to pay up a certain amount, encouraging sustainable funding in preparation for future withdrawal of donor funding. The co-financing policy was implemented in three phases, namely the initial self-financing phase, a preparatory transition phase and an accelerated transition phase.

In the initial self-financing phase of co-financing, each country was required to pay a flat rate amount of US$0.20 (Ksh25.85) per dose of any Gavi-supported vaccine, and Gavi would match up the balance. In the second phase, the country would increase its contribution by 15 per cent per year, and in the last phase it would increase by 35 per cent per year.

With co-financing support and financial backing from Gavi, Kenya has made significant strides in expanding vaccine coverage, minimising disease outbreaks, and reducing the overall disease burden in the country.

President of the Kenya Paediatric Association (KPA), Dr Supa Tunje, described immunization as “the second most effective public health intervention after clean, safe water for controlling infectious diseases.”

Speaking to Willow Health, Dr Tunje said, “Vaccines lead to savings in hospitalizations, lost wages by parents and long-term disabilities. They ensure quality and productive life for children throughout their life course.”

A study examining 73 Gavi-supported countries has revealed the remarkable economic impact of investing in immunisation. According to the findings, every US$1 (Ksh129) spent on vaccines between 2021 and 2030 results in a return of US$21 (Ksh2,714) in saved healthcare costs, wages, and productivity that would otherwise be lost due to illness and death.

When broader societal benefits are factored in, such as the value people place on lives saved and the overall improvement in life expectancy and well-being, the return on investment increases even further.

The study estimates that for every US$1 (Ksh129) invested, the total value returned could reach as high as US$54 (Ksh6,980). These findings strongly support sustained funding for immunisation programs, highlighting vaccines as one of the most cost-effective health interventions available.

Despite experiencing frequent shortages and stockouts of essential childhood vaccines, Kenya is on course to address the challenges hindering supply, including global vaccine supply bottlenecks.

“The Ministry is establishing strategic vaccine reserves in all 47 counties through a program that will be sustainably financed and efficiently operated,” Health Principal Secretary Dr Ouma Oluga said last month.

Dr Oluga reassured Kenyans that “No child will miss a single dose of any vaccine,” thanks to the government’s Zero-Dose Catch-Up Mechanism initiative, which provides vaccines to children who have missed scheduled doses, ensuring they still receive full protection.

In the recent Gavi Global Summit where world leaders pledged more than US$9 billion in support for Gavi for its next five five-year strategic period, chair of the Gates Foundation, Bill Gates, lauded the financial commitments, terming them as “one of the best investments countries can make today in the world’s future.”

“In a constrained budget environment, it’s even more important to focus aid funding on the investments that really work,” said Gates. “I don’t know of anything with a higher impact per dollar in terms of saving and improving lives.”

Research & Data Analysis by Riziki Shaher & Dr Mercy Korir

Visualisation by Sara Okuoro & Vincent Ngaca

Graphics by Arthur Mbuguah