In Kenya, Prof Moses Obimbo, an obstetrician and researcher, announced plans to launch the PPH School to enhance access to affordable clinical skills.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has issued new global standards for faster response to postpartum bleeding to save mothers’ lives.

For decades, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) was treated as an emergency only after a woman had lost 500 millilitres of blood.

But global health experts have cut the threshold to 300 millilitres in new changes jointly announced last month by WHO, the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) and the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM).

WHO notes that PPH affects millions of women annually and causes nearly 45,000 deaths, making it one of the leading causes of maternal mortality globally.

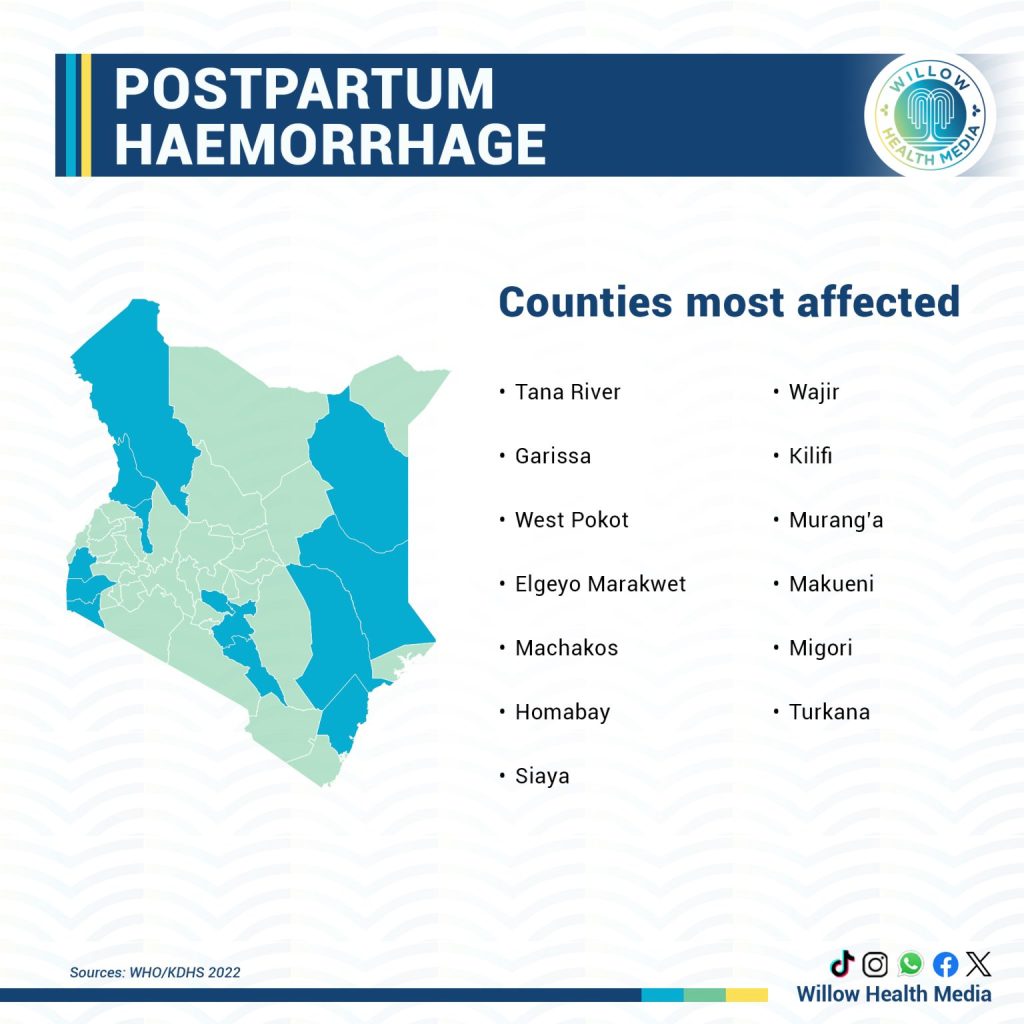

Across Africa, PPH is responsible for nearly a third of all maternal mortality cases, while in Kenya, it accounts for over 34 per cent of maternal deaths, according to the Ministry of Health.

Dr Jeremy Farrar, WHO’s Assistant Director-General for Health Promotion, Disease Prevention, and Control, termed Postpartum haemorrhage as “The most dangerous childbirth complication since it can escalate with such alarming speed. While it is not always predictable, deaths are preventable with the right care.”

The new global guidance aims to change how quickly frontline medics recognise danger, act and save mothers, especially in settings where every minute counts and blood loss often goes unnoticed until it’s too late.

“Typically, PPH has been diagnosed as a blood loss of 500ml or more. Now, clinicians are also advised to act when the blood loss reaches 300ml, and any abnormal vital signs have been observed,” read the statement in part.

It went on to advise medics to “use calibrated drapes, simple devices that collect and accurately quantify lost blood, so that they can act immediately when criteria are met.”

Translating this urgent new standard into consistent practice demands universal, high-quality training.

In Kenya, Prof. Moses Obimbo, an obstetrician and researcher leading the PPH Foundation, announced plans to launch the PPH School, a training platform for making clinical skills affordable and accessible.

Speaking at the recent FIGO Conference in Cape Town, Prof. Obimbo said the initiative uses Virtual Reality (VR) and Extended Reality (XR) to teach essential lifesaving techniques.

“This technology-driven approach ensures that healthcare workers from doctors and midwives to clinical officers are trained and reskilled annually on PPH management,” he said.

The aim is to build muscle memory and confidence in managing obstetric emergencies. Prof. Obimbo added that the VR/XR tool is scalable and can be deployed across Africa, creating a consistent standard of care in a field where every second counts.

President of the Kenya Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society (KOGS), Dr Kireki Omanwa said that facilities lacking precise measurement tools, like a simple calibrated drape that collects and quantifies lost blood, relying on the 500ml marker often meant waiting too long.

Dr Omanwa adds that reducing the amount of blood loss to 300ml “Will trigger us to begin intervening a lot earlier than later. We will reduce the incidences of PPH and also the chances of women dying from PPH.”

His sentiments echo those of Dr Farah, who added that the new “Guidelines are designed to maximise impact where the burden is highest and resources are most limited, helping ensure more women survive childbirth and can return home safely to their families.”

Experts say the updated threshold represents a new philosophy in maternal care. Instead of focusing on a fixed number, the guidance emphasises early recognition, rapid response, and team-based management.

In Kenya and across Africa, the guidance is expected to strengthen ongoing efforts such as the E-MOTIVE trial, which tested the use of calibrated drapes and a standardised “first response bundle.” The approach reduced deaths and severe bleeding by more than 60 per cent in pilot hospitals.

“Early measurement and response are simple but powerful steps,” says Dr Margaret Maimbolwa, a maternal health specialist in Nairobi. “By recognising bleeding earlier, we give mothers a fighting chance before the situation turns critical.”

As countries update their national protocols, WHO and its partners are urging governments to ensure that blood measurement tools, uterotonics, and trained personnel are available at all delivery points. The hope is that no mother will die from a cause that is now both predictable and preventable.