As the world marks World Suicide Prevention Day today, Kenya stands at the forefront of a mental health revolution.

Dalton Musamula, an intersex person living in Kenya, surveyed life sometime and “I just felt like this was now my end…(that) I just don’t have to exist anymore…”

He felt abandoned and rejected, a reality for billions on the edge of despair, worldwide.

But in that darkest moment, something profound happened as Dalton heard an inner voice telling him, “You can’t do this to your mum. She has gone miles for you, done a lot for you …tomorrow I might change her life,” he recalled, adding that thought alone pulled him back and “made me not to take the poison.”

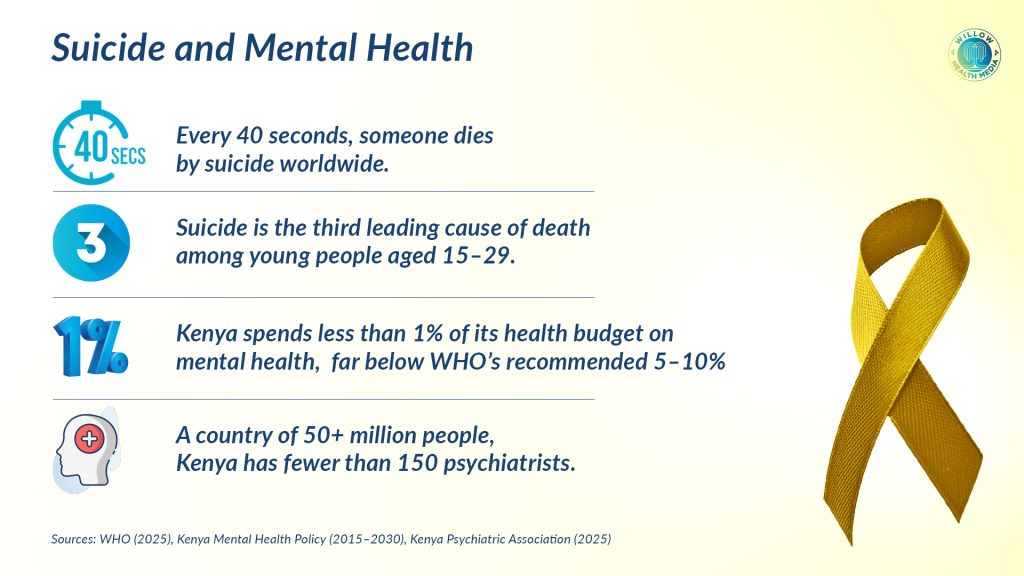

Every 40 seconds, someone dies by suicide somewhere on the planet, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). But behind each statistic lies a human story of pain and struggle, but also potential for recovery. In Dalton’s case, it was constant rejection from his father and the various schools for being an intersex person.

This World Suicide Prevention Day, September 10, 2025, is marked as Kenya takes bold policies on mental health support.

For starters, on January 9, 2025, High Court Judge Lawrence Mugambi declared Section 226 of the Kenyan Penal Code, which makes suicide a criminal offence, unconstitutional.

For decades, colonial laws subjected suicide attempt survivors to potential imprisonment

“Criminalising attempted suicide indignifies and disgraces victims of suicide ideation… for actions that are beyond their mental control,” Judge Mugambi ruled in the landmark case filed by Charity Muturi, the Kenya Psychiatric Association, and the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.

For decades, Section 226 subjected suicide attempt survivors to potential imprisonment of up to two years or fines. This colonial-era law criminalised mental health struggles and created insurmountable barriers for those seeking help.

However, the court recognised that such criminalisation violated fundamental constitutional rights to equality, human dignity, and the highest attainable standard of health.

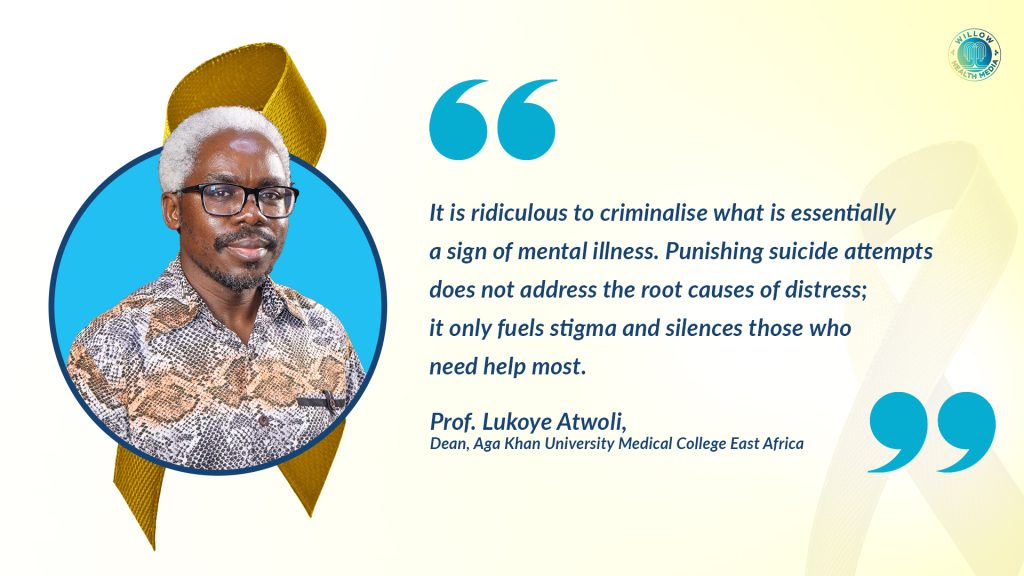

In an earlier interview with The Star, Prof Lukoye Atwoli, Psychiatrist and Dean at the Aga Khan University Medical College East Africa, welcomed the ruling, terming Section 226 “obnoxious, colonial and ancient”, arguing that “It is ridiculous to criminalise a sign of mental illness.”

In a parliamentary petition reported in sections of local media in August last year, Prof Atwoli noted that “Criminalising suicide attempts not only fails to address underlying mental health issues but also perpetuates shame and stigma surrounding mental illnesses.”

Decriminalisation of attempted suicide is not an endorsement of suicidal behaviour

Prof Lukoye also noted that criminalising suicide creates a constitutional conflict as it contradicts Article 43 of the Constitution that guarantees every person … “Right to the highest attainable standard of health, which includes the right to healthcare services, including reproductive healthcare, and a person shall not be denied emergency medical treatment.”

Dr Mercy Karanja, President of the Kenya Psychiatric Association (KPA), emphasised that “the decriminalisation of attempted suicide is not an endorsement of suicidal behaviour but rather a strategic approach to prevent suicidal deaths by removing barriers that deter individuals from seeking help.”

KPA outlined three key implications of this ruling: ending stigma and discrimination to encourage help-seeking, prioritising humanistic care over punishment, and aligning Kenya with global best practices.

“Moving forward, the association has called for implementation of the National Suicide Prevention Strategy, increased investment in mental health services, complete repeal of outdated penal code provisions, and community efforts to foster supportive environments for mental health discussions,” said Dr Karanja.

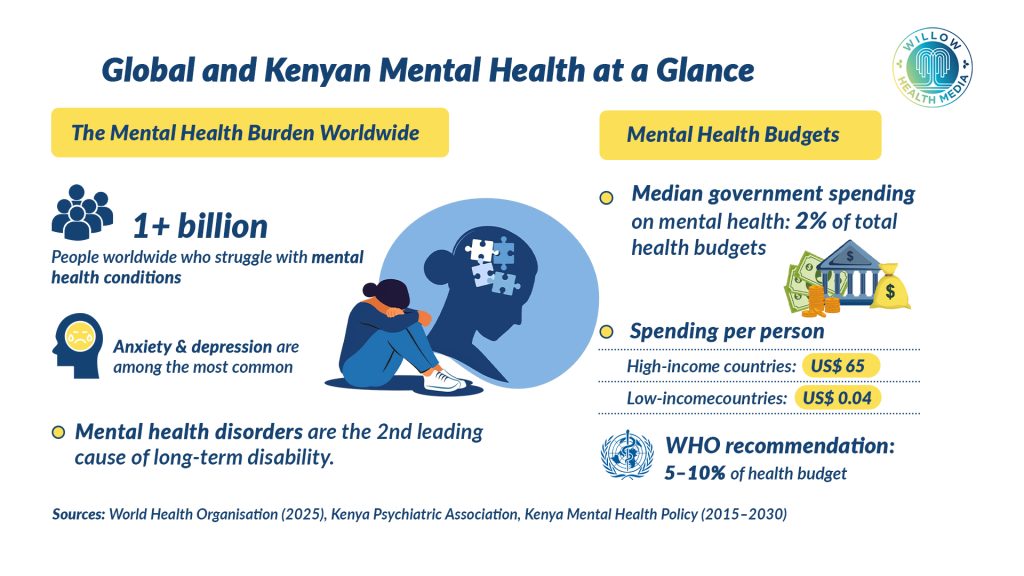

Globally, over one billion people live with mental health disorders, with anxiety and depression the most prevalent, according to WHO.

Suicide is influenced by social, cultural, biological, psychological and environmental factors

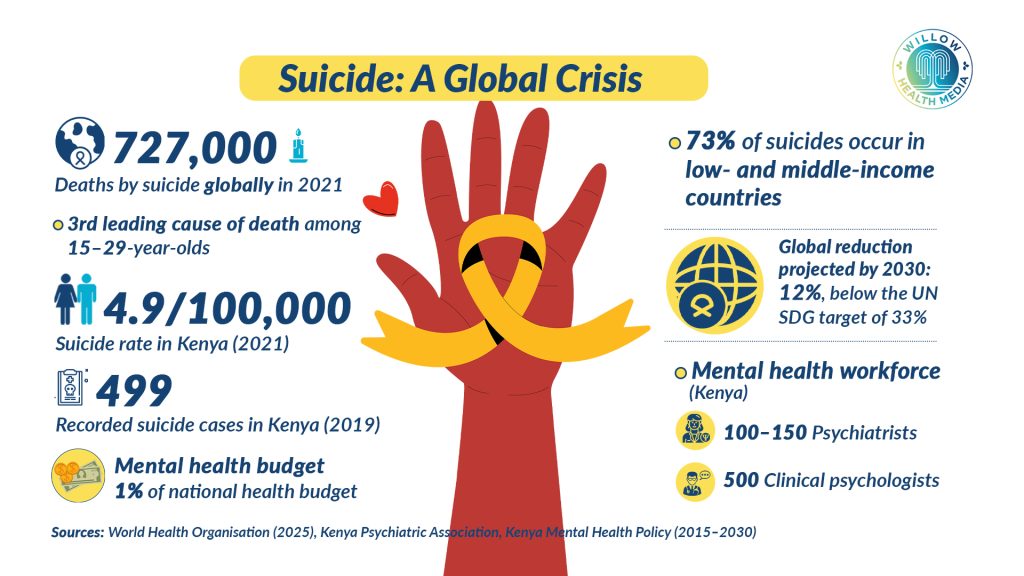

Suicide claimed about 727,000 lives in 2021 alone and remains a leading cause of death among young people globally.

The reasons for suicide are multifaceted, influenced by social, cultural, biological, psychological, and environmental factors, according to WHO. They range from financial problems, relationship disputes, chronic illness, violence, discrimination and social isolation.

Vulnerable groups include refugees and migrants, indigenous peoples, LGBTI persons, and prisoners. Depression and alcohol use disorders with previous suicide attempts significantly increase risk, especially in high-income countries.

Despite the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of a one-third reduction in suicide rates by 2030, current projections indicate only a 12 per cent decline. The vast majority-73 per cent- of suicides occur in low- and middle-income countries.

Closer home in Kenya, WHO data shows a suicide rate of about 4.9 per 100,000 people, but these figures likely underrepresent the true scope due to stigma and underreporting.

Kenya has a shortage of mental health professionals, limited access to services

The March 2023 policy brief from the Ministry of Health noted the rising cases of reported suicide cases from 1,157 in 2018 to 1,462 in 2019. The numbers remained high with 1,388 cases in 2020 and 1,596 in 2021, highlighting an urgent need for targeted mental health interventions and preventive measures.

The Kenya Mental Health Policy (2015-2030) shows that Kenya has a shortage of mental health professionals, limited access to services, and inadequate funding, leaving millions without needed care. It underscores the urgent need for investment in training, infrastructure, and community-based support.

Data from KPA shows that Kenya has about 100 to 150 psychiatrists and fewer than 500 clinical psychologists for more than 50 million people.

WHO’s 2024 Mental Health Atlas confirms that low- and middle-income countries face extreme shortages in mental health workers, far below the global average of 13 per 100,000 people. In low-income countries, fewer than 10 per cent of affected individuals receive care. Community-based and outpatient services are limited, while psychiatric hospitals still handle most admissions, often involuntarily and for extended durations.

The challenge is compounded by chronic underfunding, with mental health services receiving less than one per cent of the national health budget, far below the WHO’s recommended five to 10 per cent.

Low-income countries spend as little as $ 0.04 (Ksh5.19) on mental health

WHO data shows that globally, spending on mental health averages two per cent of total health budgets, unchanged since 2017. High-income countries spend up to $ 65 (Ksh 8,437.90) per person, while low-income countries spend as little as $ 0.04 (5.19).

Given this complex web of factors, targeted prevention strategies are essential, and WHO’s LIVE LIFE initiative outlines four evidence-based steps to prevent suicide: limiting access to common means like pesticides, firearms, and high-risk medications, and working with the media to promote responsible reporting.

The strategy also emphasises building socio-emotional life skills among adolescents and ensuring early identification, assessment, treatment, and follow-up for individuals showing suicidal behaviours.

These interventions must be supported by situation analysis, multisectoral collaboration, awareness raising, capacity building, financing, monitoring and responsible media reporting.

Research shows sensationalist coverage of suicide can lead to copycat deaths, the “Werther effect”, while stories of hope and recovery can prevent suicides through the “Papageno effect.”

Media reports should avoid detailed descriptions of suicide methods

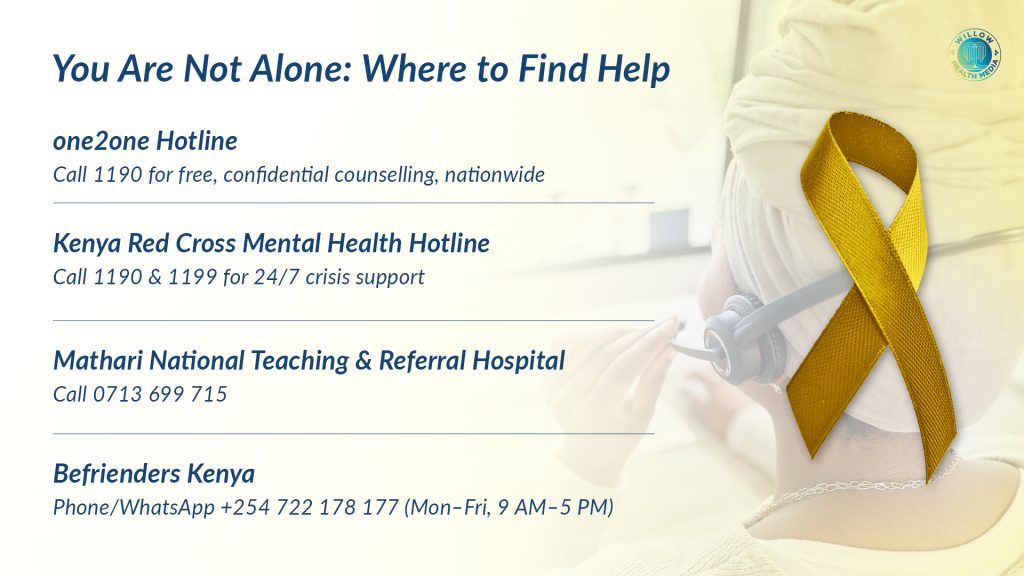

Media professionals also play a crucial role in suicide prevention by reporting responsibly, providing accurate information about available help services and highlighting coping strategies and recovery stories. Reports should avoid detailed descriptions of suicide methods or locations and exercise particular caution when covering celebrity suicides, as these can influence vulnerable audiences. Every story should also include contact information for support services to guide those who may be at risk towards immediate help.

Kenya’s decriminalisation of suicide aligns with WHO recommendations and removes a significant barrier to help-seeking.

The 2020 Taskforce on Mental Health declared mental illnesses a national emergency, calling for legislative reforms and increased funding.

However, stigma remains one of the greatest obstacles to suicide prevention. Too often, people contemplating suicide don’t seek help because of shame, fear of judgement, or legal consequences. Kenya’s bold move to decriminalise suicide, therefore, sends a message that mental health struggles are health issues like any other and not criminal matters.

As the world marks World Suicide Prevention Day, Kenya’s example is a mirror for other nations, while Dalton’s story of survival shows that behind statistics are real faces of people in need of help.