With traditional medicine, ‘You can pay with chickens, goats, or promise to pay later,’ says Chivatsi Chiguba, a village elder. ‘The herbalist trusts the patient. Healing is about mutual faith, community, and nature’s remedies.’

Mwanaisha Said, a mother of three and food vendor in Mombasa County, spent three years searching unsuccessfully for treatment for a mysterious illness, even in hospitals. The symptoms included: falling and shaking in her sleep, inability to speak or socialise normally during episodes and “I also could not attend burials, as I couldn’t look at dead bodies.”

Mwanaisha, who claimed she suffered attacks by jins, sought help from some traditional healers who predicted, “I will die within a month. I used to fall, and when asleep, I shake when I wake up. I couldn’t talk with people well, I just kept quiet during the attack by jins, and I also could not attend burials, as I couldn’t watch a dead body. In some places where I sought medication, people used to say I will not make it and I will die within a month,” explained Mwanaisha.

She claims she was healed from harmful spirits after bathing twice daily for two months using saffron and herbs soaked in water, under the instructions of Mohammed Hassan, a traditional healer famously known as “Mzimle Kaimu”. Mwanaisha says she can now talk to people, attend funerals and remain calm, free of harmful spirits that are attacking and making her sick.

Indeed, in most parts of the coastal region, seeking medical attention for mysterious illnesses from traditional healers is a common practice.

Mohammed Omar Kanyoe, a boda operator from Kikambala, says turning to traditional healers was his last resort after attempts with Islamic religious men, Christian prayers, and a Kilifi hospital failed to heal his 14-year-old daughter Mariam Kadenge from similar attacks by Jins. Kadenge reckons “traditional medicine should be taken into consideration and not be seen as black magic.”

My daughter got better through bathing with herbal water and recitations to chase bad spirits

Kanyoe told Willow Health Media that family and friends advised seeking prayers from Islamic and Christian clergy, “and they prayed for her, but she did not heal”. He then went to Kilifi hospital, “but the doctor said she had no symptoms of any sickness, and her situation worsened, and we tied her legs and arms to make her stay in one place and not run all over.”

Finally, his fellow boda boda operators advised him to try a traditional medicine man, and “after a week, my daughter, through herbal medications, bathing with herbal water and recitations to chase bad spirits away, she got better”. explained Kanyoe, adding that traditional medicine is the last refuge when all fails, and it should “not be seen as black magic, provided one gets medical help”.

Traditional healers are sought after by coastal people for various reasons ranging from traditional beliefs, financial muscle, culture and social learning.

In Kwale County, for instance, ancient healing traditions thrive as community wisdom, while among the Duruma people, ancient forests and places of worship known as Kayas still offer refuge, especially during drought or epidemics.

In Mnazi Mmoja village, Bimba Kokota, 80, still prays in the river, believing prayers are more directly answered. Others prefer visiting traditional healers instead of modern health facilities, because of the belief that some ailments have roots in dark forces and traditional causes, and only traditional methods and experts can deal with them.

Hassan treats conditions modern medicine often misses and swears belief is half the cure

Mupa Nyawa Chibogo, a herbalist and healer who treats those burdened by aching bodies and unsettled minds, listens carefully before turning to nature’s remedies. Some patients ask for virility boosters; others seek prosperity, protection from dark forces, or even business success. Many women request love potions or womb-cleansing herbs, hoping to restore harmony and fertility in their relationships.

Mupa also treats stomach ailments and childhood illnesses marked by scaly skin, a condition often believed to be “Chirwa,” linked to a husband’s infidelity. She says fear of modern medical procedures in modern hospitals drives many women to seek herbal remedies during the day, while men tend to visit in the evenings, preferring the cover of discretion.

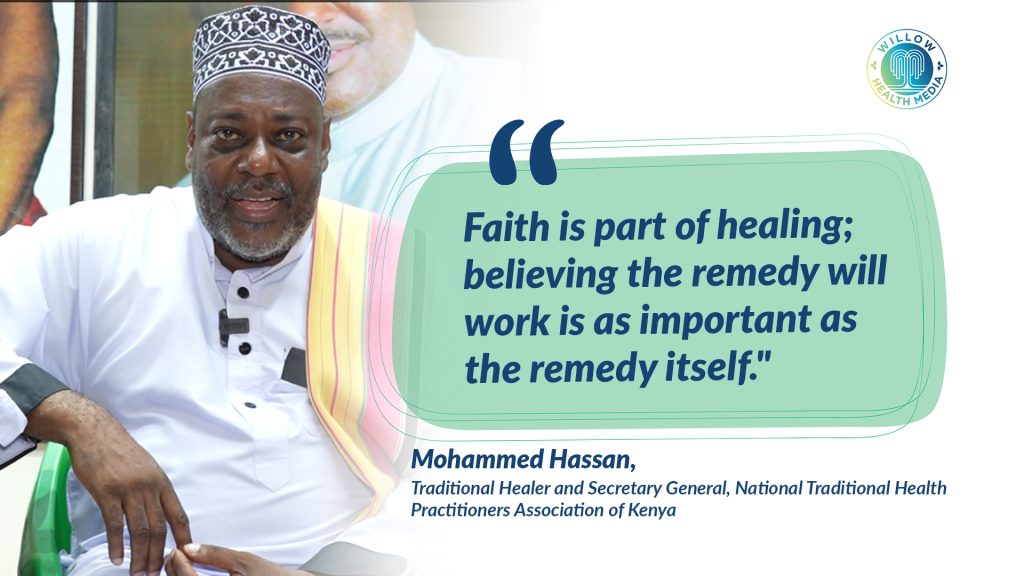

Others, like “Mzimle Kaimu” Hassan, Secretary General, National Traditional Health Practitioners Association of Kenya, use plants purely for healing. With generations of knowledge, he treats conditions modern medicine often misses and swears that belief is half the cure.

“My clients come to me with hope. Some have tried hospitals with no success,” he says. “Faith is part of healing; believing the remedy will work is as important as the remedy itself.”

Dr Milton Kengo Danda, a researcher based in Kwale, explains how the trust operates on two levels.

“One level believes that illnesses stem from human malice (uchawi) performed by a mchawi (witch). The remedy lies in counteracting it with the help of a mganga (healer),” he noted.

“The healer, often assisted by a mwanamaji, uses herbs and animal sacrifices, often guided by spiritual chants or kuruma.”

Coastal residents who can’t afford SHA opt for affordable traditional practitioners

The other advantage of traditional medicine in the coastal region is affordability, and as Chivatsi Chiguba, a village elder in Mwavumbo, notes, “You can pay with chickens, goats, or promise to pay later. The herbalist trusts the patient. Healing is about mutual faith, community, and nature’s remedies.”

Dr Amos Lewa Mwavita, a biochemist and herbal doctor, concurs that some coastal residents cannot afford Social Health Authority (SHA) payments and opt for affordable traditional practitioners accepting chickens, goats, or delayed payment.

According to a 2016 Ministry of Health study, many individuals are influenced by religious extremism to completely reject modern medical care, turning to unproven traditional practices.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some religious sects in Kenya discouraged their members from getting the vaccines. Others encourage the shunning of blood transfusions, and others reject hospital treatment altogether.

Religious extremism only worsens matters.

The Shakahola Cult massacre, in which over 400 people were starved to death in 2023, is still fresh in Kenyan’s minds. Chibonga explains that “A religious leader can use specific potions to attract more followers and make congregants believe in their divine power. This practice, known as Fungaliza, manipulates people into giving away their possessions in the name of faith. Sadly, many are unaware they are being exploited.”

During the pandemic, ICU wards in the Coast region were mostly empty as residents feared stigma and opted for traditional treatment, while in Nairobi, patients ran out of wards.

“During the COVID-19 time, we treated so many government officials in our herbal Centre, but due to WHO specifications and timelines, the medication could not be tabled for use,” Mwavita said.

31% of Kenyans consult traditional healers or religious leaders

Joseph Mwarandu of the Malindi Cultural Association observes that spirituality, cultural traditions, and modern medicine often intersect, especially in mental health care. “Some ailments escape hospital diagnosis but find healing through traditional remedies,” he says.

He adds that collaboration took time to develop: “It took a long time for modern doctors to accept working with traditional herbalists. Today, Malindi Hospital has a traditional medicine desk that works hand in hand with nurses to support patients’ mental care”.

Traditional medicine remains a mainstay in Kenyan healthcare.

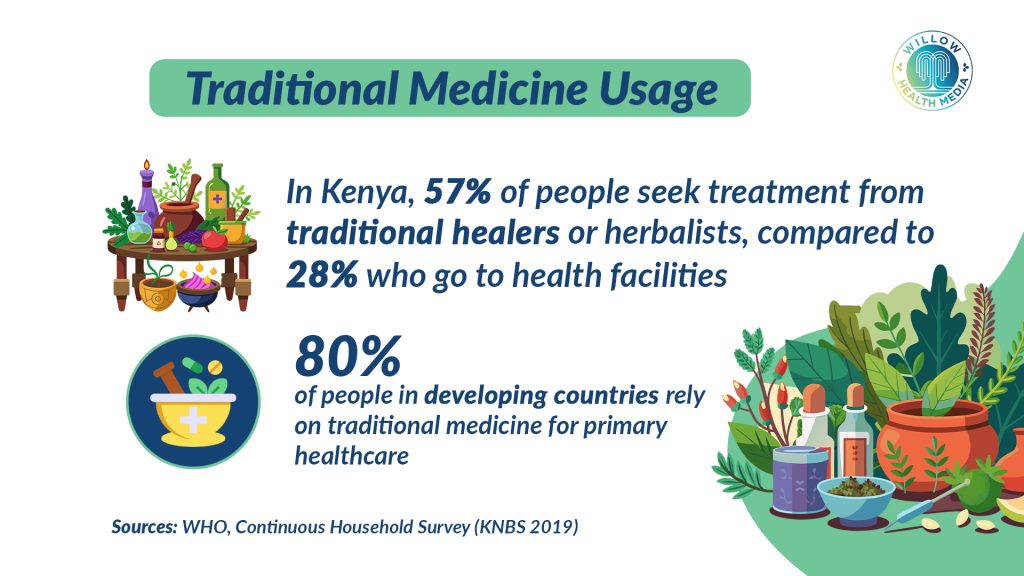

A 2019 Kenya National Bureau of Statistics report revealed that 31.4 per cent of people with illness or injury were diagnosed by traditional healers, versus 28.3 per cent who received a diagnosis from professional health workers.

The KNBS report further suggests that more than 70 per cent of Kenyans rely on traditional healers as their primary healthcare source, with 57 per cent seeking treatment from traditional healers or herbalists, compared to 28 per cent who use formal health facilities.

Parliament is now advancing the 2025 Kenya Medical Research Institute Bill, which proposes integrating traditional and alternative medicine into the national health system, with KEMRI overseeing regulation, research, and approval, including penalties for unsafe products.

The Kenya Medical Research Institute Bill, 2025 will oversight traditional medicine practices

President Ruto endorsed the Quality Healthcare and Patient Safety Bill, 2025, on July 29. The proposed law aims to overhaul the health sector and create an independent authority dedicated to quality care and patient safety.

The Kenya Medical Research Institute Bill, 2025, introduced by Seme MP James Nyikal, would create legal oversight for traditional medicine practices long used by Kenyans but often lacking quality control.

The Kenya Medical Research Institute Bill states, “The government shall recognise and integrate traditional medicine in a manner that complements the conventional healthcare system.”

If passed, KEMRI will conduct clinical and biochemical research on traditional treatments to verify effectiveness and safety. The institute will support regulatory agencies in maintaining product standards and monitoring herbal products.

The Bill outlaws unauthorised ingredients, products without proven health value, and remedies without toxicology testing. It makes operating in unsanitary conditions an offence.

Mohammed Kitsao Kadenge, a herbalist who treated COVID-19 cases, advocates for policy integration: “The government should formalise traditional medicine. We need hospital-based traditional practitioner desks to bridge the gap. This would reduce unnecessary deaths and make healthcare more inclusive.”

KEMRI, with the Ministry of Health and research organisations, aims to create innovation environments for comprehensive case management and precision medicine evaluation. During the recent KEMRI Annual Scientific Health conference, diseases like cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases were identified for personalised medicine approaches.

This direction aligns with the WHO global draft strategy on traditional medicine 2025- 2034, which aims to ensure research and safety standards are blended into traditional medicine to support people’s health and well-being.

As Kenya is struggling to incorporate traditional medicine with modern medicine, African countries have diverse approaches to traditional medicine, with some, like Cameroon and Madagascar, integrating it into their national health systems through policy, regulation, and practitioner collaboration.