For many Kenyans, health insurance feels like paying to attract bad luck. Toss in tight wallets, poor saving habits, and deep-rooted superstition, and it’s no wonder the insurance card stays buried

Samuel Njuguna never considered health insurance important until he realized his family’s future depended on it. Before that, it was just another automatic payroll deduction.

“We don’t see insurance as an investment in our well-being,” says the media marketer and father of two. “The transition from NHIF (National Hospital Insurance Fund) to SHA (Social Health Authority) has intensified confusion. Misinformation is winning…”

Like many Kenyans, Njuguna observed how families fundraise for medical bills or pay out of pocket, yet “Some hospital bills can impoverish a family in one transaction. Having insurance is better than not having it.”

Dennis Gicheru, an Eldoret-based events manager, cites culture and religion as key barriers. “Christians, he says, view planning for illness as an ‘abomination’ and “We’d rather avoid the reality and take cover in the Bible.”

This mindset creates family conflicts as when Gicheru bought his mother a medical cover, she rejected it, telling him to “curse the spirit of sickness” instead and thus calls for increased public awareness.

Insurance agent Andrew Avwuki concurs many Kenyans are socialized to “only care about health when it’s an emergency” and no body wakes up wanting insurance until they need it. Then there’s cultural resistance from superstitious beliefs as “Some clients say ‘tema hio mate’ (avoid that jinxed talk) when I mention health coverage.”

Culture of viewing health crises as emergencies to be handled communally

Avwuki highlights the irony of Kenyans who place bets daily but won’t buy health covers. “In betting, chances are that you will lose your money, get addicted and sink into depression, while health insurance means you have peace of mind and cover in case of a medical emergency. Which one is better, lose a bet and be depressed or have insurance that can cater for your mental wellness?” posed Avwuki.

Bishop Gideon Mudenyo of Blessed International Fellowship explains the communal mindset in most cases, “a culture of viewing health crises as emergencies to be handled communally, not individually.” He advocates for flexible payment plans such as “Tailored packages with weekly or monthly premiums would work better than annual payments.”

Psychologist Serah Muindi of Hopewell Counselling, identifies deep-rooted mistrust as “Even middle-class Kenyans doubt insurance value, especially when public schemes don’t cover private hospitals. People believe you must be admitted to benefit, creating reluctance.”

Another psychologist, Trizah Muthoni of Aviva Mental Health Services, abandoned SHA for private insurance after frustrating experiences and now argues “NHIF worked wonderfully, but SHA’s unclear benefits forced me to switch for my parents’ care.”

Irene Biwott faced another harsh reality around a similar issue. Her surgery would only be covered by SHA if she paid a full year’s premium upfront, which was impossible for the marketer and entrepreneur. “What’s the value of such policies when I need surgery now?” She questions.

Negative perceptions make Kenyans treat insurance as non-essential

Kenyans often see insurance policies as too complicated, especially waiting period rules. This leads many to view covers as useless – most only want insurance when sick and need instant coverage. But this clashes with how insurance works, making people doubt its worth.

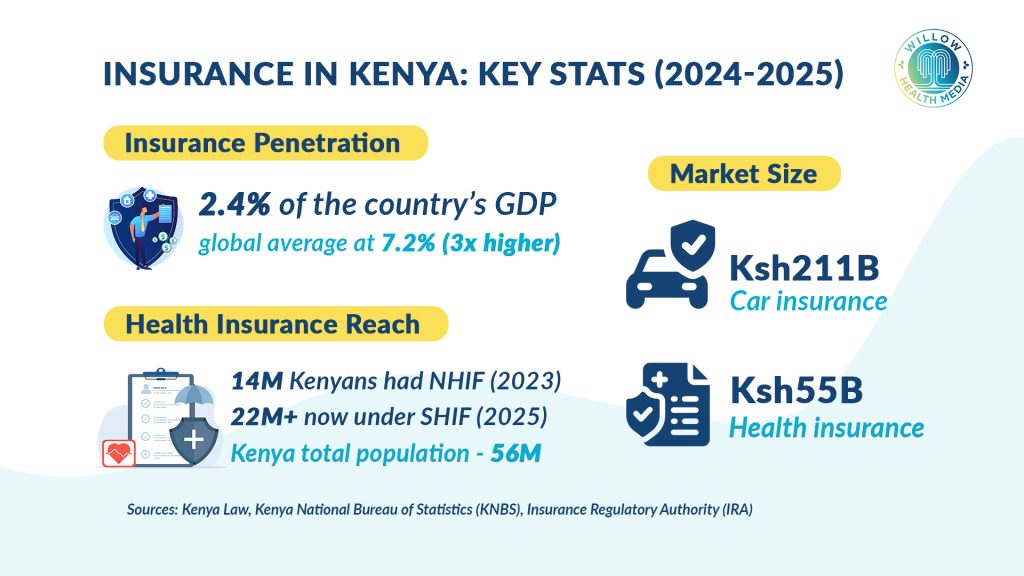

The Insurance Regulatory Authority (IRA) attributes low uptake to three factors: “Negative perceptions make Kenyans treat insurance as non-essential, allocating minimal income to it,” while acknowledging the impact of poor saving culture and low disposable incomes.

Indeed, for jobless teacher Corazon Chebii, income remains the biggest hurdle. “My TSC colleagues have automatic deductions, but those with irregular incomes struggle.” She adds that insurers often disappear when claims are made, leaving many unprotected.

A study by John Murigi Mburu from USIU-Africa titled “Penetration and Uptake of Insurance in Kenya” identified systemic issues like “Poor agent integrity, slow claims processing, fraud, and customer misguidance on policies all contribute to the trust deficit.”

A Trans Nzoia teacher, who requested anonymity as she was still undergoing treatment, shared a frustrating experience: “I was hospitalized for malaria with a Ksh299,000 bill. The insurer paid only Ksh70,000, claiming malaria ‘doesn’t warrant admission.’ I spent a whole day appealing before they cleared the balance.” Such experiences breed widespread distrust.

Johannes Misembo, a consultant at Upsurge Insurance Solutions, blames misinformation and commission-driven agents as they promise full family coverage, then claims for dependents get rejected.

Another problem is half-truths. When an agent says “a Ksh100,000 premium will offer a cover of Ksh1 million and not specify that the optical limit is Ksh10,000, and when a claim of Ksh20,000 is denied, they feel cheated and quit,” offers Misembo.

Only a few denominations that don’t believe in science oppose health insurance

Religious beliefs have for years been another barrier with some denominations discouraging members from seeking healthcare. However, religious leaders are now changing their stance.

Sheikh Abubakar Bin, North Rift Council for Imams and Preachers of Kenya (CIPK) Chairperson, explained previous reservations about health and life insurance have evolved since life is sacred and anything that supports it, like good health, is permissible.

“Sicknesses are costly to treat and the faithful are at liberty to get health insurance covers which reduces the frequency of moving from one mosque to another to raise money for treatment. God has a plan for all of us, and we also have a part to play,” Bin explained.

Pastor Pancras Ogomo Ngira, Senior Pastor, Word of Light Centre, Eldoret, agrees: “Only a few denominations that don’t believe in science and treatment from a hospital could oppose health insurance.

Taking a health cover is not a lack of faith as insinuated by some quarters, it’s a wisdom issue…of caring about one’s health.” He advises believers who feel health insurance weakens their faith to take it for their dependents instead.

Make health insurance mandatory like car insurance. People will appreciate it later.

“The Bible reminds us…there’s a time we’ll get sick and we’ll need to act like the wise ants which store food in times of abundance to cover them when scarcity comes. It is careless not to take health insurance when we can afford it,” the cleric emphasised, calling for increased awareness on health insurance.

Pastor Patrick Simiyu of Patsim Advisory Networks adds that Christians require health covers as believing God is a healer does not detach one from the world they currently live in.

“I believe in divine healing, and whenever I or my family is faced with a health challenge, we first reach out to God in prayer. We have been healed severally, but that does not mean we did not seek medical attention from doctors,” Simiyu weighed in.

Says Simiyu: “Jesus said anyone who wants to build a mansion must sit down and count the cost; health insurance is part of this planning.”

Peter Odima, a union leader, highlights how casual workers suffer: “Employers ignore WIBA (Work Injury Benefits Act) requirements because workers don’t know their rights.” He describes unsafe working conditions: “Casuals handle cement without masks because bosses know they’re desperate.”

Potato farmer Antony Kirui suggests tough enforcement: “Make health insurance mandatory like car insurance. People will appreciate it later.” Insurance experts agree – car coverage thrives because it’s legally required.

The new Social Health Authority faces skepticism. During public dialogues, many questioned the premium formula. SHA’s “lipa mdogo, mdogo” (small installments) plan now aims at helping out through weekly contributions.

Unlike Kenya, Rwanda’s health insurance uptake is on the ascendance due to its social approach, where donations from charities and grants are pooled together with citizens’ contributions to ensure coverage of the indigent.

Graphics by Brian Wekesa

Great insights from diverse sources on a critical topical that needs national attention. Good job👏.