About 800 Kenyan nurses migrate annually to the USA, Canada and the UK over low pay, poor working conditions and limited opportunities for career progression

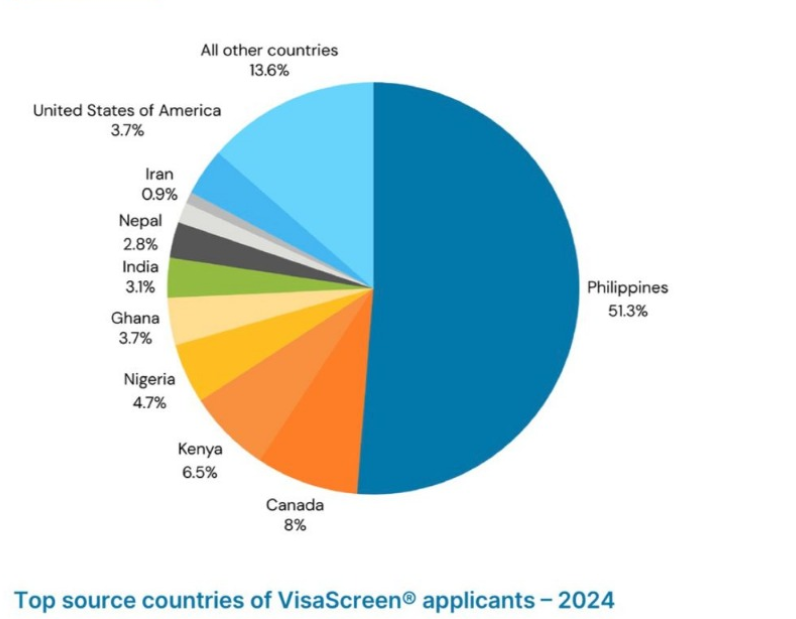

Kenya leads the continent in the supply of nurses abroad, ahead of Nigeria and Ghana, new data reveals.

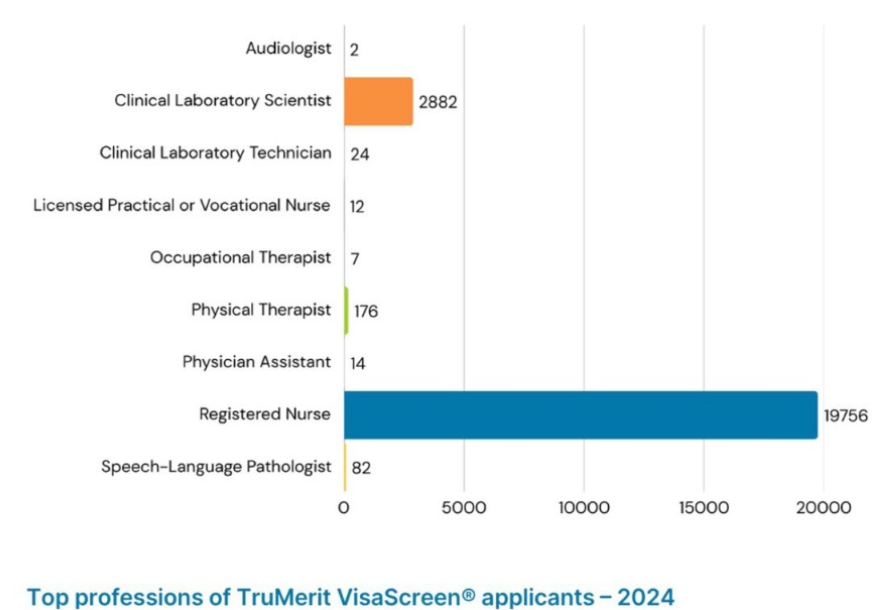

The three countries now account for a combined 15 per cent of applicants from Africa, according to the 2024 TruMerit Nurse Migration Report.

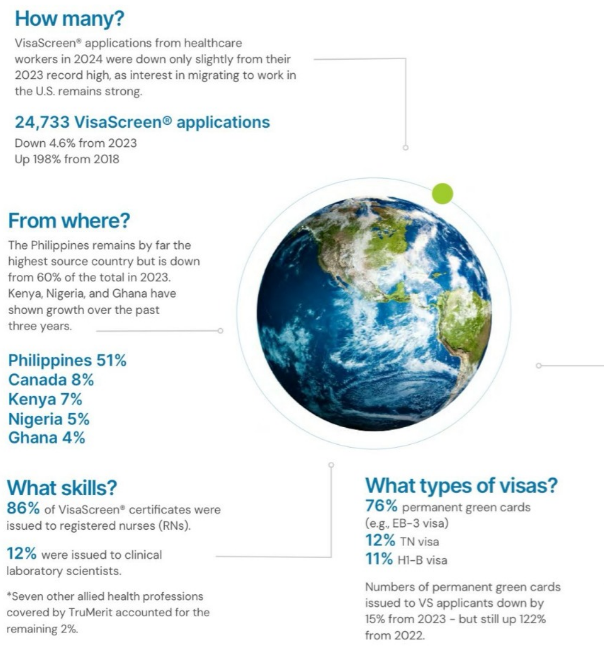

Kenya alone contributes 6.5 per cent or half of the nurses seeking the VisaScreen certification- the key credential for foreign-trained nurses and allied health workers seeking to practice in the United States, where about 24,733 healthcare professionals sought migration.

The Philippines is still the world’s top source of English-speaking nurses. Over half (51%) of nurses applying to work in the USA were Filipino, according to the report.

This rise is not without cost. Take Kenya, where over 800 nurses leave annually, most to the USA, Canada, or the UK as part of the global healthcare labour market, according to the Kenya National Union of Nurses.

Other countries where nurses are taking their care include Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand for their clearer immigration processes. Others are moving to South Africa and Botswana, which suffer nursing shortages.

The reasons are as practical as they are painful: low salaries, poor working conditions, and limited opportunities for career progression. While headlines scream about “brain drain,” the migration of nurses is also spurred by political power relations, foreign policies, ‘health diplomacy,’ post-pandemic staffing shortages in developed countries and human decisions.

Philip Kirwa, the CEO of Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) in Eldoret, lamented how “At least 60-100 skilled and long-serving nurses resign annually to take well-paying jobs abroad, resulting in a deficit of over 1,000 nurses.”

Alfred Obengo, the former president of the National Nurses Association of Kenya, told a local online platform that most of them were “well-experienced nurses with a wealth of knowledge. They are competent and specialists in different health fields.”

The impact of the migration of nurses is most felt in the counties where hospitals are finding it harder to maintain continuity of care.

Maternity wards, emergency rooms, and ICUs have become revolving doors, with many facilities now relying on short-term staffing measures.

Women, who make up the majority of nurses globally, face an added layer of complexity in their migration journeys. Safety concerns, workplace discrimination, and isolation in foreign countries remain underreported challenges. In destination countries, many women encounter subtle bias when applying for leadership roles or negotiating contracts.

Healthcare systems need quality nurses, not just quantity. TruMerit Report details rigorous verification steps, including credential checks, English tests, and license validation to ensure foreign nurses meet US standards. These verification systems face challenges after a UK scandal where over 700 nurses were investigated for exam cheating, highlighting the need for better international regulation of nursing credentials.

Advocacy groups like Nursing Now stress the need for gender-aware support systems for migrant nurses. Since nursing is mostly women, WHO officials in Africa warn that this creates specific risks and vulnerabilities for these workers when they migrate internationally.

The nurses are needed most by hospitals in rural USA and other underserved regions, which rely heavily on foreign-trained nurses to fill critical staffing gaps.

The American Association of International Healthcare Recruitment (AAIHR) notes that one in six nurses in the US is trained overseas. However, in early 2024, visa processing delays and changes to immigration policy — including the end of the H-1B visa — prevented many foreign nurses from working in the US, forcing healthcare employers to seek alternative staffing solutions.

The EB-3 green card is still the main path for foreign nurses, with 76 per cent of applicants pursuing permanent residency. Canadian and Mexican nurses typically use TN visas (12 per cent), while H-1B visas account for 11 per cent. Green card approvals fell 15 per cent from 2023 but remain more than double the 2022 numbers.

Meanwhile, destination countries are no longer just Western powers. Filipino nurses are increasingly eyeing Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand, attracted by more predictable immigration pathways. Germany and Ireland continue to tap Latin America. And within Africa, countries like South Africa and Botswana are cautiously beginning to recruit foreign nurses to offset their own shortages.

Migration is evolving, not evaporating.

The 2024 data suggest one thing clearly: nurse migration isn’t slowing down. It is shifting. And as Africa steps into the spotlight and policy battles heat up on both ends of the migration pipeline, one truth is certain — the world’s health systems are more connected than ever before.

And every nurse on the move is carrying more than a credential. They are carrying a story — of global health, human resilience, and the quiet power of care.