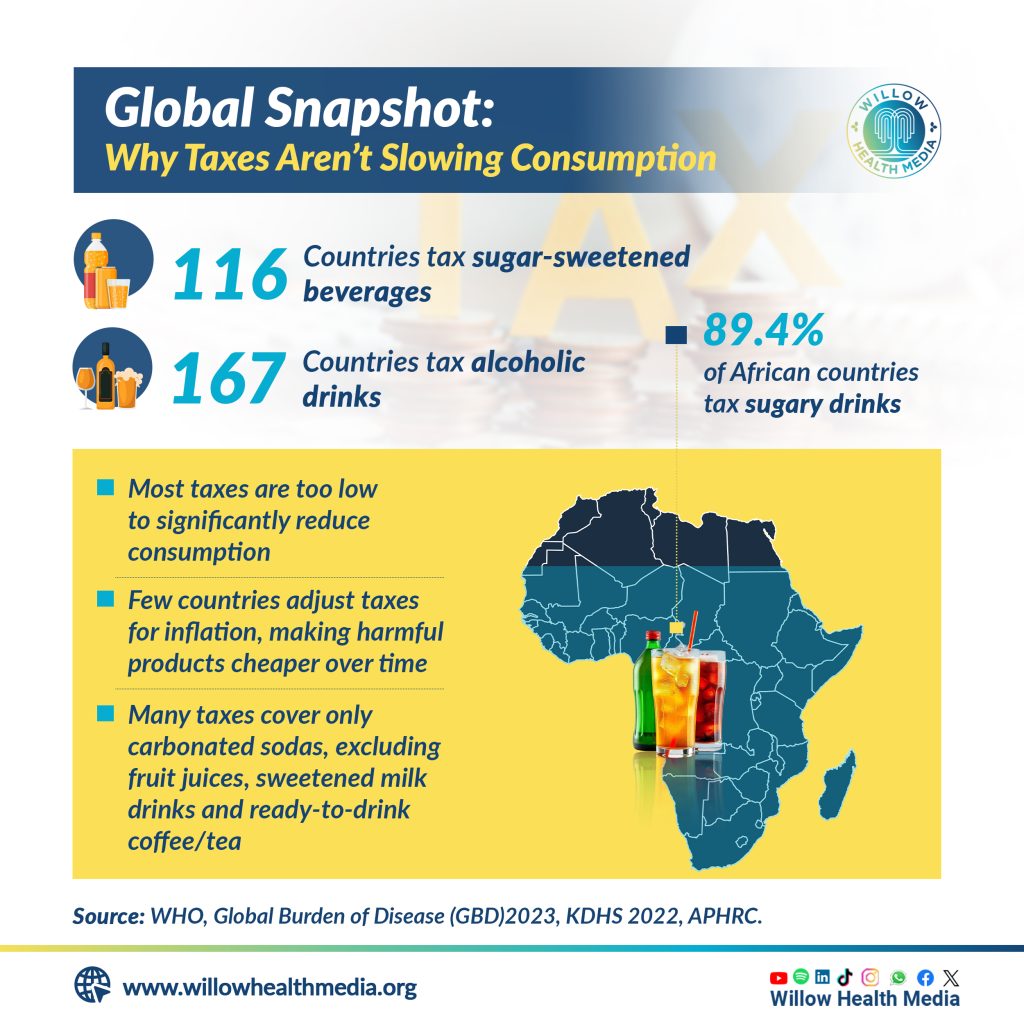

Despite the African region leading in taxing sugary drinks far higher than Europe or other high-income regions, the tax levels are generally too low to trigger behaviour change among consumers.

As sugar-sweetened beverages and alcohol become cheaper and more widely available across the world, health experts are now warning that countries are paying a steep price in rising noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), injuries, and mounting healthcare costs.

Two global reports released by the World Health Organization (WHO) in early 2026 show that while many countries have introduced taxes on sugary drinks and alcohol, most policies are too weak to protect public health.

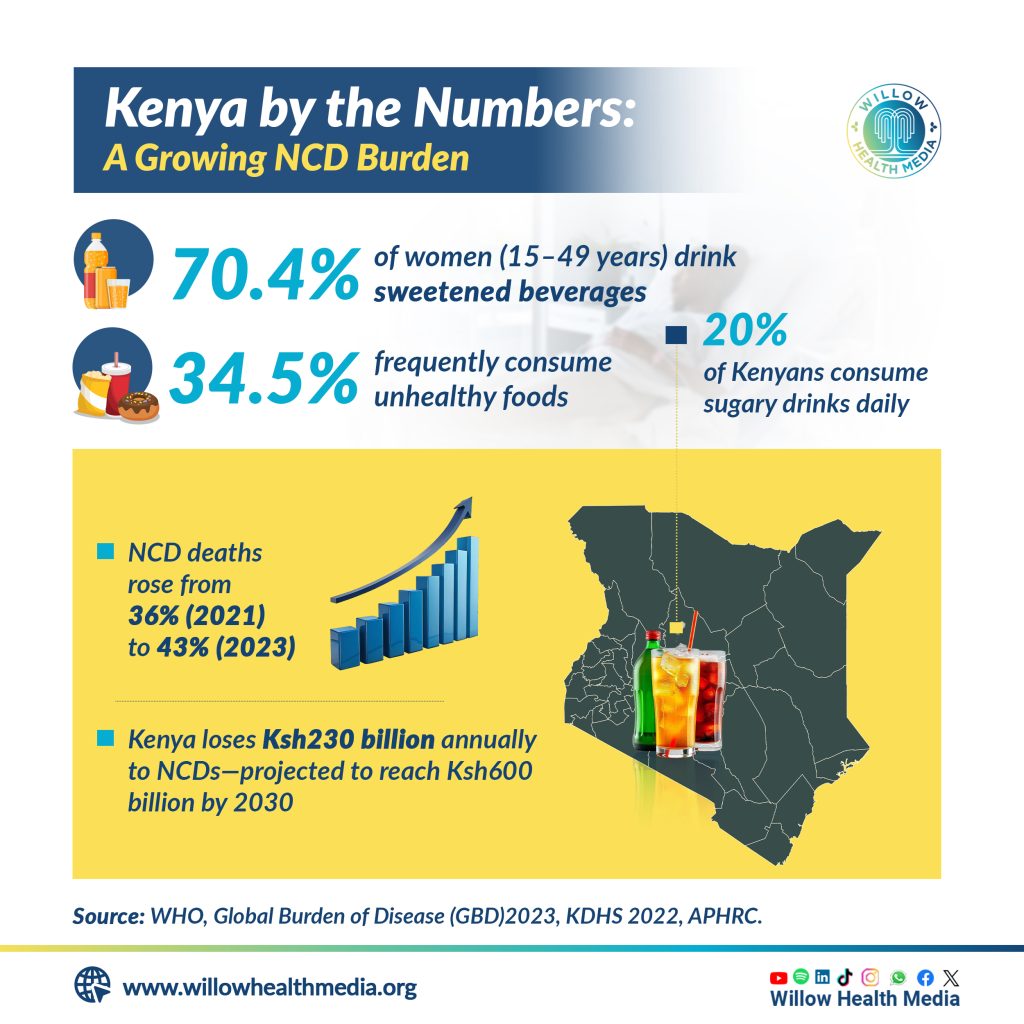

For Kenya, where consumption of ultra-processed foods and sweetened beverages is growing rapidly, the findings raise urgent questions about affordability, regulation, and prevention, especially among children and young adults.

According to a WHO Global Report on the Use of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxes, 2025, sugary drinks are among the leading sources of free sugars in many countries, despite offering little to no nutritional value. High intake is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dental caries, and other diet-related conditions.

Globally, at least 116 countries apply national-level excise taxes on at least one type of sugar-sweetened beverage. The WHO African Region leads, with nearly 90 per cent of countries taxing sugary drinks, which is far higher coverage than Europe or other high-income regions. However, the report underscores a major flaw: tax levels are generally too low to change consumer behaviour.

In most countries, sugar taxes account for only a small share of the retail price, meaning consumers barely feel the difference at the point of purchase. In addition, many high-sugar products such as fruit juices, sweetened milk drinks, and ready-to-drink teas and coffees often escape taxation altogether.

Alcohol has become more affordable, or at least not more expensive, in most countries since 2022

WHO warns that as incomes rise and tax rates remain static, sugary drinks risk becoming even more affordable over time, particularly for young people with limited disposable income. Increased affordability has been identified as a key driver of higher consumption and rising obesity rates.

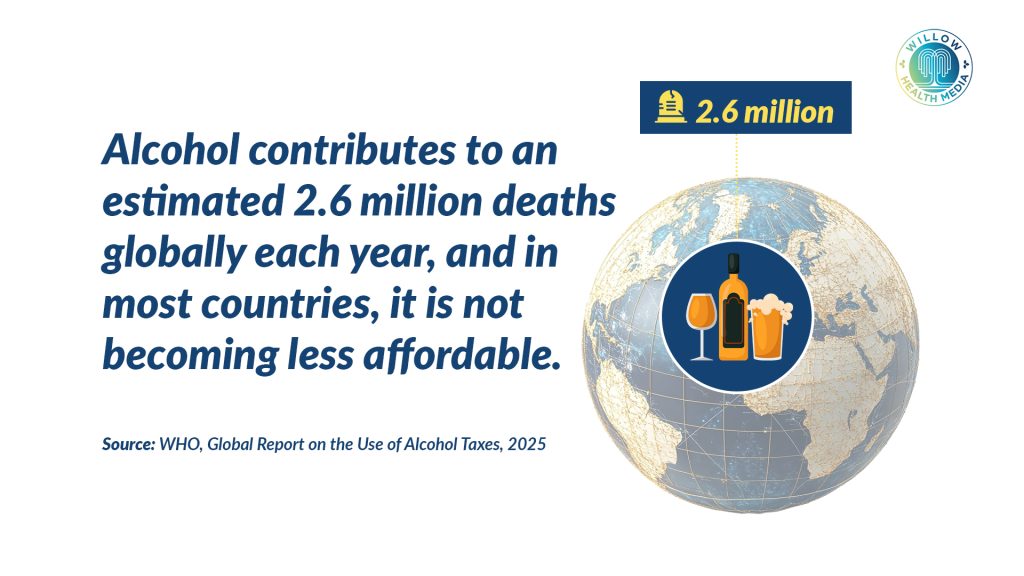

A similar pattern emerges from the WHO Global Report on the Use of Alcohol Taxes, 2025. While 167 countries tax beer, wine, or spirits, alcohol has become more affordable or at least not more expensive in most countries since 2022.

The main reason is that taxes have failed to keep pace with inflation and income growth. The report shows a wide variation in alcohol tax design, with some countries taxing through alcohol content and others by volume or value. In several countries, wine remains untaxed, creating loopholes that undermine health objectives.

WHO emphasises that low alcohol taxes fuel higher consumption, which is linked to injuries, violence, liver disease, cancers, and other NCDs. Globally, alcohol contributes to an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year, making it one of the leading risk factors for death and disability.

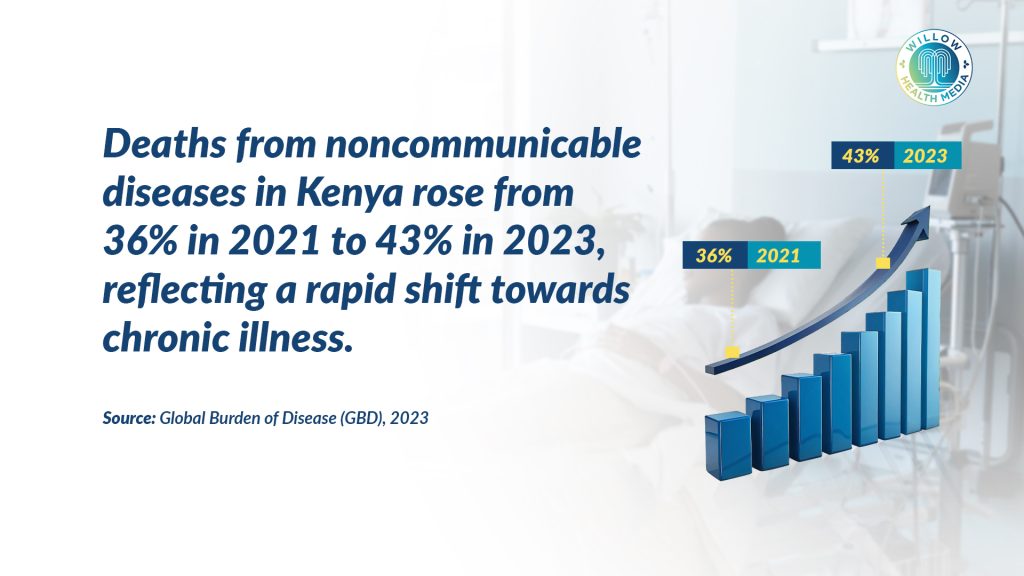

Kenya is already experiencing the consequences of weak regulation of unhealthy products. Data from the Global Burden of Disease (2023) shows that deaths from noncommunicable diseases rose from 36 per cent in 2021 to 43 per cent in 2023, highlighting a steady shift toward chronic illness.

Between 2019 and 2022, total sales of unhealthy foods and beverages doubled from 600 million litres to 1.2 billion litres

The 2022 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey paints a similar picture of changing diets. About 20 per cent of Kenyans consume sugary drinks daily, while 70.4 per cent of women aged 15-49 report drinking sweetened beverages. More than a third of adults frequently consume unhealthy foods.

Speaking during a stakeholder forum convened by the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in November, Dr Gershim Asiki said market data illustrates just how quickly consumption is rising.

“Between 2019 and 2022, total sales of unhealthy foods and beverages doubled from 600 million litres to 1.2 billion litres,” he said. “That’s equivalent to about 15 to 22 litres per person, and some individuals are consuming hundreds of litres each year.”

Much of this consumption now happens at home rather than in restaurants, reflecting increased availability through supermarkets and retail outlets.

Nutritionists warn that affordability is not just an economic issue; it has direct biological consequences. Betty Okere, a nutritionist, explained that sugar has addictive properties that make frequent consumption more likely once people are exposed, and “Once the brain gets familiar with sugar, it will always ask for more.”

She further noted that excessive sugar intake drives increased calorie consumption and raises the risk of obesity, which in turn contributes to hypertension, heart disease, inflammation, some cancers, insulin resistance, and diabetes.

“If these products that contain extra amounts of sugar are cheap, more people can afford them,” Okere said. “We are exposing a larger group – children, young adults, and even older adults to noncommunicable diseases that are actually preventable.”

Most sugar-sweetened beverages come with empty calories; big on taste, but zero nutrition

She added that sugary drinks also create a misleading sense of fullness. “When someone is very hungry, and they take sugar, it gives a false feeling that they are no longer hungry, but they crash very fast. Soon you want another drink, and another one.”

This cycle, she said, can be more addictive than alcohol and particularly dangerous for children, who often have small amounts of pocket money and easy access to cheap sugary products. Another overlooked impact of sugary drinks and ultra-processed foods is micronutrient deficiency, even among people who appear overweight or obese.

“Most sugar-sweetened beverages come with empty calories,” Okere explained. “They are big on taste but contain no nutrients.”

As a result, people may consume excess calories while lacking essential nutrients such as iron or potassium. “You may find someone who looks big, but they are anaemic or at risk of heart complications,” she said.

Okere contrasted this with whole foods like fruits, which contain sugars that are absorbed more slowly and come with fibre and essential nutrients, “Yet because of price, someone may choose a 20-shilling drink over a papaya or mango that costs the same,” she said.

Beyond health, the economic impact of rising NCDs is substantial. According to a World Bank analysis cited by APHRC, Kenya loses about Ksh230 billion every year due to NCDs, a figure projected to rise to Ksh600 billion by 2030 if current trends continue.

“These are healthcare costs, productivity losses, and premature deaths,” Dr Asiki said. “They affect families, employers, and the entire economy.”

WHO argues that health taxes are among the most effective tools to reverse these trends by reducing consumption while generating revenue for overstretched health systems. However, only about 13 per cent of countries that tax sugary drinks earmark the revenue for specific purposes such as health promotion or NCD prevention.

In Kenya, existing taxes often group sugary drinks together with other “luxury goods,” including bottled water, weakening their health impact. According to Dr Asiki, for taxes to discourage consumption, they should exceed 20 per cent of the product’s value.

40 million people die annually from conditions linked to tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy diets

Okere agrees, noting that taxation can work on two fronts: prevention and promotion. “When prices go up, fewer people can afford these products, and consumption comes down,” she said. “At the same time, the revenue can fund nutrition education and health promotion.”

She added that tax revenues could also be used to incentivise manufacturers to reformulate products with less sugar or to support companies producing healthier foods through rebates or subsidies.

Researchers caution that taxes alone are not enough. Dr Shukri Mohamed of APHRC said a bundle of policies , including front-of-pack labelling, restrictions on marketing to children, healthier food procurement in schools and hospitals, and subsidies for nutritious foods, can shift consumer behaviour more effectively.

“If a soda costs 100 shillings today and 500 tomorrow, you will think twice about buying it,” she said. “Price matters, but information and availability matter too.”

Speaking during a recent roundtable exploring how sin (excise) taxes are reshaping Africa’s healthcare financing, Jonathan Munge, Project Manager at Axum, stated that evidence from countries like South Africa and Mexico shows well-designed health taxes reduce consumption of harmful products and increase public revenue.

Dr Sultani Matendechero, Deputy Director at Kenya’s Ministry of Health, urged the reframing of sin taxes, “Not from the perspective of revenue generation but from the perspective of a public health intervention,” by making access to these products so punitive that the consumption dwindles.

The WHO’s reports deliver a clear message: taxing sugary drinks and alcohol works, but only if taxes are strong, broad, and regularly updated. Weak and outdated systems allow unhealthy products to remain cheap, fuelling rising NCDs and injuries while draining health systems and economies.

Graphics by Brian Wekesa.