Jane is 17, pregnant, and alone in the world—just a birth certificate and an urgent hope the Social Health Authority might see her, hear her, help her.

It is a cold Nairobi morning, and I am standing at the edge of a narrow alley, waiting. Then I see her: small-framed, shoulders hunched beneath a faded green jumper stretched over her six-month pregnant belly. Her eyes are tired. Too tired for a 17-year-old. We will call her Jane.

There is no father in sight.

“He said he wasn’t sure if the baby was his,” she says quietly. Her voice is steady, but there’s a sadness beneath it that no teenager should carry.

Jane, from Kayole in Nairobi’s Eastlands, has no parents. No siblings. First raised by her grandmother, then passed on to an aunt. Now, with a baby on the way, she has no medical card, no insurance—just a birth certificate and a desperate need for help.

Testing the System: Can SHA Deliver?

I am here undercover, but today I am also her companion, walking with her to test if Kenya’s Social Health Authority (SHA) is living up to its promise of universal care for the vulnerable. Teenage pregnancy in Kenya is not rare, but for many like Jane, who fell pregnant in Form Two, it becomes a battle for dignity and access once the bump begins to show.

Our first stop is Pumwani Maternity Hospital, Nairobi. A receptionist listens to Jane’s situation, nods sympathetically, but says we need a referral from a local health centre first.

It’s not hostility. Just policy. But for Jane, it’s another hurdle. Another door half-opened.

Referral Runaround: Too Many Doors, Not Enough Keys

The next day, we head to Njiru Health Centre, about 20 kilometres away along Kangundo Road. The facility has grown from a humble dispensary into a Level 4 hospital. I blend in as Jane’s escort, mic hidden beneath my scarf. We explain her case.

The first officer is blunt:

“You’ll have to pay for services in cash.”

Jane’s face falls. She has nothing on her.

A second officer joins us. We start over: Jane’s age, her pregnancy, her lack of family support. This time, there’s a flicker of understanding.

“Well… it might be possible,” she says, “but confirm with Mama Lucy Hospital first.”

The referral is not denied but deferred. Still, it’s progress. We were using Uber, but were she alone, Jane would have been commuting between all the health facilities using public transport.

Finally, a Break: SHA Steps In

Mama Lucy Kibaki Hospital in Nairobi’s populous Umoja estate is about five and a half kilometres from Njiru Health Centre. There, we finally catch a break. The SHA registration officer listens patiently before sending us to SHA’s Buruburu office, over six kilometres away.

There, we meet someone who doesn’t just follow protocol. She leads with empathy. She asks Jane for her birth certificate. That’s all she needs.

An OTP is sent. Jane receives a temporary identifier—her digital lifeline to care.

“She won’t pay anything,” the officer reassures us. “The government covers her and her baby until she turns 18.”

Jane exhales. Her eyes soften. For the first time, I see something shift: a quiet relief.

The System That Could Work—If People Do

According to Robert Ingasira, former Acting CEO of SHA, this is how the system is designed to work:

“Teenage mothers are now uniquely identified in our system. They go through means testing. If they can’t pay, they are sponsored by the government.”

SHA has introduced unique identifiers for teenage mothers, allowing them to be tracked and cared for without confusion in the system. Ingasira explains that a household profile is created, including that of both the mother and newborn, making it easier to monitor and extend benefits.

“We’ve trained healthcare staff in Level 4 and 5 hospitals, CHPs, and even Huduma Centre officers to assist with registration and means testing,” he adds. “Primary care services at Levels 2–4 are free for anyone who’s registered.”

But despite the system’s design, its execution still depends on the human factor. Jane’s story is a testament to this. She was met with indifference, confusion, and finally, care. In each hospital, we found a different face of the same system.

Beyond Jane: Who Else Is Falling Through?

SHA also caters to other vulnerable groups: orphans, street children, prisoners, and refugees. Ingasira says their premiums are covered by national or county governments, or sponsors such as social protection agencies.

“We’re working with the Department of Children’s Services to register orphans and street children, and with the Ministry of Correctional Services for people in lawful custody,” he said. “The key is registration. Once you’re in the system, you can access care.”

And yet, the question remains: how many Janes are falling through the cracks?

How many teenage mothers get turned away at the first hospital and don’t come back? How many don’t know they can register at Huduma Centres or through community health promoters? How many don’t have someone to walk with them through the maze?

Jane was lucky. She found the right people—the kind ones. But systems should not depend on chance.

A Glimmer of Hope

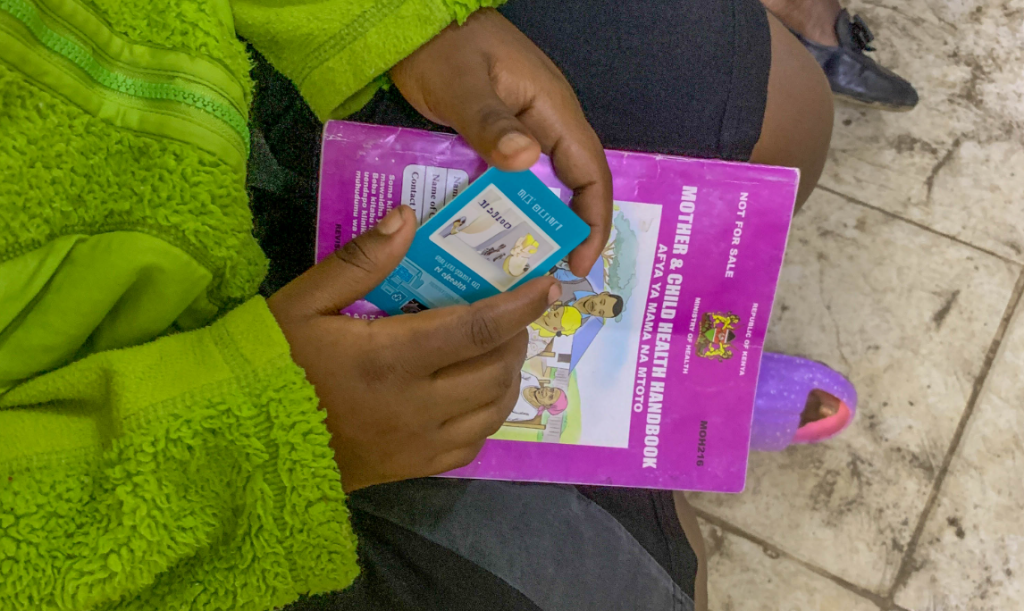

As we step out of the SHA office in Buruburu, Jane clutches her new identifier like a passport.

“At least now, I know my baby will be okay,” she says, a fragile smile blooming on her face.

This journey began in silence, in a dusty alleyway filled with questions. It ends with a glimmer of hope—not just for Jane, but for the possibility that SHA, despite its rough edges, can work.

According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), in 2023, there were 140,774 registered live births to mothers aged 15 to 19, accounting for 11.8% of all registered births in the country. Additionally, 2,049 live births were registered to girls under the age of 15, representing 0.2% of total births.

In total, 48,633 births were registered to adolescent girls aged below 18 years, underscoring the persistent challenge of teenage pregnancy in Kenya.