Women in Turkana were beaten up and forced to deliver before time, while newborns took goat milk as sick mothers couldn’t breastfeed them– Cecilia Longolea, Community Health Promoter

Under the blazing Turkana sun in Namortotio village, Community Health Promoter (CHP) Cecilia Ekwom Longolea walks from one home to another, checking on mothers and babies.

Her first stop is at Cecilia Akai’s house – a small Atot (traditional Turkana hut). Akai, a mother of three, is nursing her two-month-old baby, delivered safely at Natira dispensary. Longolea examines the baby, confirms the mother is breastfeeding exclusively, and reminds her of her next clinic visit.

Next, Longolea meets Lucia Echwan, who is expecting her second baby in December. The two share a painful past of once suffering at the hands of traditional birth attendants during childbirth. “I almost lost my life the first time,” says Echwan. “At the hospital, I learned how important it is to give birth safely.”

Now, Longolea monitors her pregnancy closely, checking blood pressure, nutrition and any signs of danger. She’s happy to report Echwan is in good health and attending her antenatal clinics.

“A birth plan helps a mother prepare early; she knows where she’ll deliver and when to move closer to the hospital,” explains Longolea.

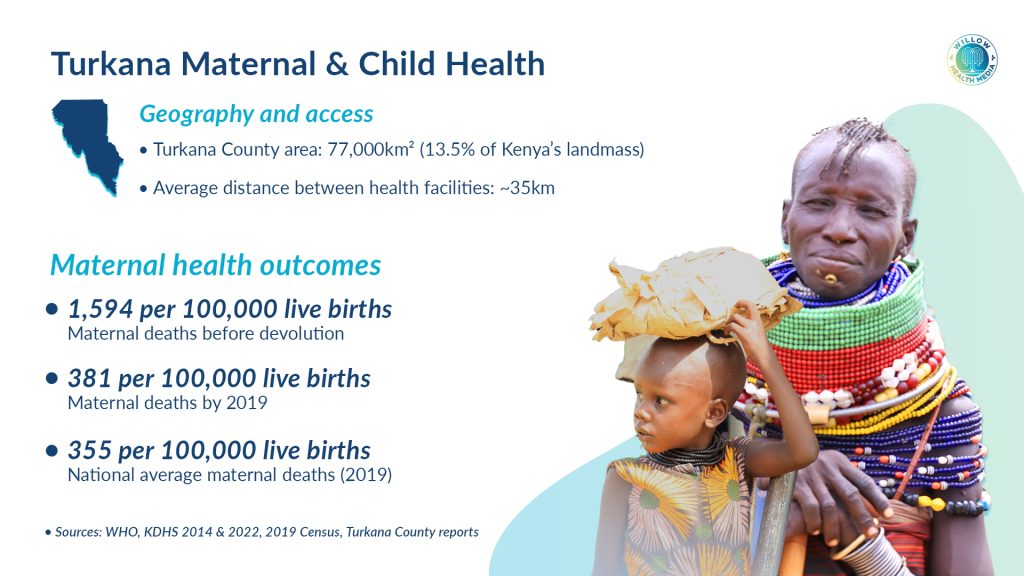

According to the county’s Head of Family Health Division, Dr Gabriel Lopodo, Turkana is one vast 77,000 km² area with health facilities about 35 kilometres apart. This makes CHPs like Longolea a lifeline for mothers and babies.

Many women gave birth at home, where one would be treated like a goat, beaten up

Before devolution, ANC clinics, nutrition and child health were alien to the Turkana due to their nomadic culture and “Many women gave birth at home where one would be treated like a goat, beaten up and forced to deliver even before the right dilation,” recalls Longolea of her own ordeal. “Tears and injuries were inevitable, and some babies ended up taking goat milk because sick mothers couldn’t breastfeed.”

But healthcare has now changed. Dr Lopodo points out that “Before devolution, we recorded 1,594 maternal deaths per 100,000 livebirths. By 2019, the number had reduced to 381 deaths, only 26 out of the national average of 355. That’s a quantum leap.”

Indeed, more mothers are attending ANC clinics and giving birth under skilled attendants, thus reducing maternal mortality fivefold, thanks to Kimormor- a One-Health approach.

Anthony Arasio from AMREF manages the Maternal and Newborn Child Health in Turkana under the USAID-funded Imarisha Jamii programme. He explains that Kimormor is a model that “Offers mobile solutions to a mobile population. To address limited access and unsustainability of healthcare access, we brought together livestock and human health needs, along with other most sought-after services like identity card issuance and birth certificate issuance. It’s a crowd puller.”

In Namanikor village, tens of kilometres from Natira, Ekom Ase and his wife Nasilan Lokaale are attending their first Kimormor event: Ase will be getting an ID card, which will enable him to register for the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF).

His livestock would be vaccinated, and children registered for birth certificates

“All our four children were delivered at home with the help of traditional birth attendants because the hospital was very far. A CHP, however, taught us the importance of child immunisation,” Ase explained. He also told Willow Health Media that his livestock would also be vaccinated and children registered for birth certificates, which was previously unheard of for pastoralist children.

One of Ase’s children received four vaccine jabs and nutritional supplements to make up for missed schedules. His wife had a Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) tape test to ascertain her nutritional wellness.

In Turkana’s male-dominated culture, it is rare for men to accompany their wives to prenatal and child health clinics. However, CHPs convinced Ase that his support was critical for his family’s health. “Men should offer leadership in healthcare too, as they provide resources needed for family treatment,” Ase argues.

The call for men to support pregnant wives to attend clinics and deliver in hospitals is now the core message at Ekitoe Angikiliok (Tree of Men), a key decision-making body in the patriarchal Turkana culture, says Nakaale Ejen, a Kraal leader.

The Turkana value for livestock is such that their health even comes second. And vaccinating both people and livestock at the same place has changed life irrevocably.

I struggled making emergency referrals of patients using donkeys; we had many deaths

Modo Eporon, leader of Ng’akile Kraal in Nadapal at the border of Kenya-South Sudan, says the Kimormor outreach is a game changer.

“More mothers and children are reached even in their migratory destinations,” he told Willow Health Media. “I used to struggle making emergency referrals of patients using donkeys to distant health centres, and we had many deaths.”

Not anymore. Eporon leads about 100 households. And his position on health matters and men’s involvement is taken as law, considering he’s a cabinet member of Ngimurok, of community religious leaders with direct revelation from their creator.

Turkana men have also been transformed into advocates against early marriages. Like Ekrin Lokon, who is helping men protect young girls as they suffer the most during childbirth, with most ending up on theatre tables for Caesarean Section deliveries.

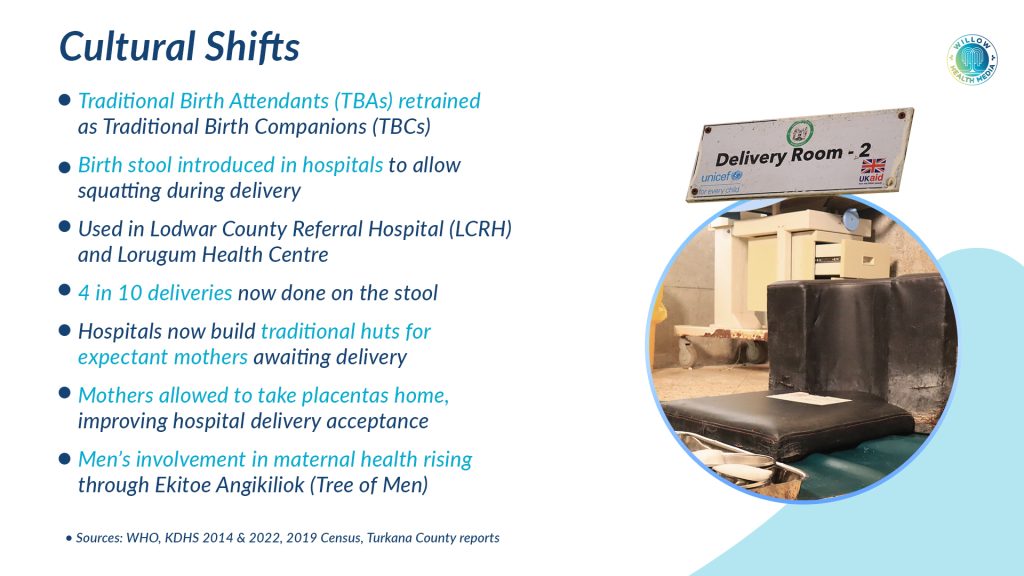

The Kimormor has successfully transformed traditional birth attendants like Nakodo Ewesit. After being trained by a CHP, Ewesit no longer delivers babies at home. Instead, she now acts as an ambassador for hospital births. Her title has even changed to “traditional birth companion” to reflect this new role of bridging modern medicine and culture.

“Delivering at home was risky as mothers with complications would sometimes die with their babies,” explains Ewesit. “Hospitals can conduct operations and help mothers deliver without losing too much blood.”

When we take care of animals, they’ll come with pregnant mothers and children for health services

Ewesit now feels Kimormor should be extended to the neighbouring Toposa community of South Sudan, as they can use “The border hospital at Nadapal, strengthens our ties and reduces feuds.”

Dr Epem Esekon, the County Executive Committee (CEC) member in charge of human health in Turkana County, has no qualms about vaccinating livestock at the Nadapal Kimormor.

“Our people’s priority is livestock. When we take care of animals, they’ll come with pregnant mothers and children for health services. We all win,” observes Esekon, adding that the Kimormor reached about 3,000 people and over 10,000 livestock.

Ekiru Kidaalo, Director of Medical Services in Turkana County, said Kimormor has increased hospital deliveries as “We’ve integrated the culturally accepted birth stool in hospitals to attract mothers who insist on delivering in a squatting position.”

Ekiru says the birth stools are common at the Lodwar County Referral Hospital (LCRH) and Lorugum health centre, and are ideal as “The squatting position is recommended by the Gynaecologists Society of Kenya as it allows women to deliver in their natural anatomical position.”

Allowing mothers to take their placentas home made them more willing to deliver in hospitals

To make it easier for mothers, health facilities in Turkana are building traditional huts where pregnant women can stay as their due date approaches. They can be accompanied by their husbands and Traditional Birth Companions.

“We create an environment that encourages them to deliver at home in our health facilities, and when they experience this, they spread the message to other mothers who then embrace hospital deliveries,” added Ekiru.

Stanley Chepyego, a nurse at LCRH, says about “Four out of 10 deliveries are done at the birth stool. We’ll need to have a special registry for this delivery to capture its success story.”

Pauline Kirwa, a senior nurse at Kerio Health Centre, says that allowing mothers to take their placentas home after birth has made them more willing to deliver in hospitals. This has led to a rise in the number of supervised hospital births.

“Simple motivators like giving mothers exercise books during ANC visits and promising them the purple Mother and Child Health handbook after hospital delivery,” Kirwa disclosed.

Dr Jacob Khaoya, Deputy Chief of Party at AMREF, pegs the success of Kimormor at designing the programme with people and their needs in mind as “Interventions that overlooked cultural values and priorities couldn’t achieve much.”

Dr Khaoya also added that collecting digital data from the Kimormor program has helped them make key decisions to sustain and improve maternal healthcare access.

Data collected by CHPs is compiled by Community Health Assistants and sent digitally to county administrators via the Electronic Community Health Information System (ECHIS).

Turkana County has already made legislations like the Community Health Services Act 2018, which largely borrow from the Kimormor approach to ensure better and sustainable health outcomes.

Graphics by Arthur Mbuguah.

Detailed, well packaged and insightful,👏