Understanding intersex is key to reducing stigma, protecting health rights, and ensuring people can live authentically without unnecessary surgeries or discrimination.

Intersex is an umbrella term for people born with biological sex characteristics, such as genitals, reproductive organs, hormones, or chromosomes, that don’t fit typical male or female definitions.

It’s a natural variation in human sex, not a disease or condition. Intersex individuals may have traits of both male and female, or they may have genitals or reproductive organs that don’t match their chromosomes.

While intersex traits are often noticed at birth, the differences aren’t always obvious at that point.

People might discover they have intersex traits at puberty or in adulthood, sometimes as a result of medical testing for fertility. In rare instances, such differences are found in autopsies, after death.

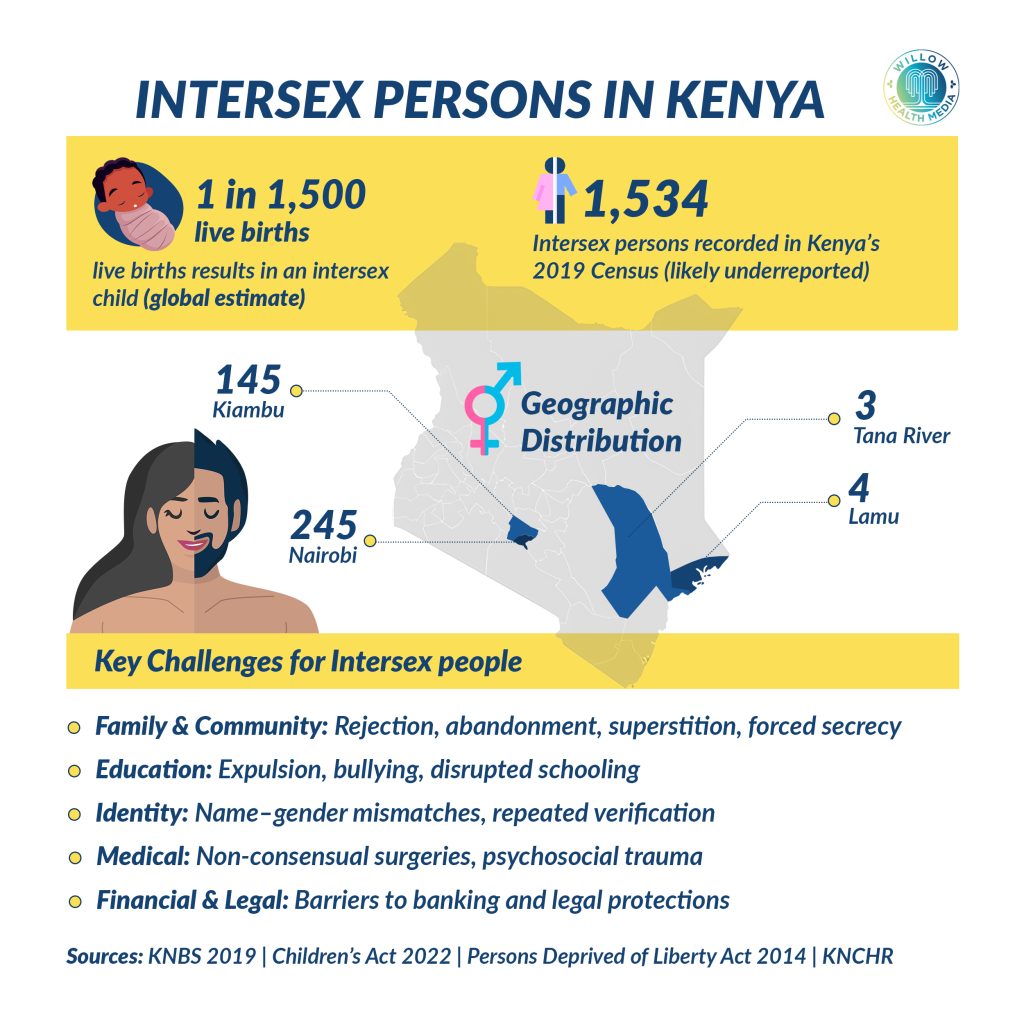

According to the 2019 census, the number of intersex persons in Kenya was 1,534, though the actual number could be higher. Nairobi leads with 245 intersex persons, followed by Kiambu with 145, and Lamu and Tana River with four and three, respectively.

Being intersex isn’t a disorder or a disease. Intersex traits can show up in about 40 ways, so there’s no description that fits everyone involved. There’s no single way an intersex person looks and no single way intersex traits affect them.

For example, one might have:

- A penis, but estrogen levels more typical of females than males

- A clitoris that is larger than expected

- A penis that is smaller than expected

- No penis, but otherwise typical male traits

- No vaginal opening

- Sex glands that contain both ovarian and testicular tissue (ovotestes)

- Ovaries and a uterus, but no vagina

- A vagina, along with undescended testes, no menstrual periods, and infertility because of a gene difference (androgen insensitivity syndrome)

In some cases, the baby’s genitalia might look completely male or completely female. In other words, they may have male anatomy on the outside but female anatomy on the inside or vice versa.

A child’s intersex status might not become obvious until puberty, when their body produces more of a hormone that is not expected according to their assigned sex.

But how does intersex come about?

According to Dr Kamau Paul Koigi, a gynaecologist and infertility expert, “by default the baby inside the uterus by around 6 or 7 weeks when genetic influence start coming into play they start off as female by default and then there is the influence of the Y chromosome and the specific genes from the Y chromosome and the production of testosterone that influence those organs to now become male, if the influence is excessive in a female then you get a female with more male like organs, and if you get a male who is developing without those hormones developing and influencing appropriately then you get a genetic male who looks more female”.

Some causes of intersex traits include Genetic conditions that affect hormone levels during development, other hormone exposures from drugs or other sources during early development, and random chromosome variations that happen at conception. In many cases, no specific cause is found.

Causes of intersex traits

- Genetic conditions,

- Other hormone exposures from drugs, other sources

- Random chromosome variations

- No specific cause

In the past, it was common for babies and young children to get surgery for traits that didn’t match their assigned gender, but that practice is being discouraged. One major reason is that people may decide later in life that they were given the wrong gender, and they want sexual organs different from those that their parents and doctors chose.

Intersex physical traits themselves usually carry no medical risks. Surgery can come with risks including: Problems with sexual functioning, reduced sensation, infertility, scarring, urinary tract infections and urine leaks.

Intersex surgery risks and complications

- Problems with sexual functioning, including reduced sensation

- Infertility

- Scarring

- Urinary tract infections

- Urine leaks

Surgery can add to future psychological distress, especially if the person later identifies as a gender different from their assigned sex.