With dwindling foreign aid, African nations turn to taxation of tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages.

As foreign aid dwindles, African countries are increasingly finding the taxation of tobacco, alcohol and sugary drinks as alternative sources of funding their healthcare burdens from products that damage public health.

Speaking at the roundtable hosted by Willow Health Media and Nigeria Health Watch, Dr Mercy Korir, the Editor-in-Chief of Willow Health Media, stressed that Africa must take ownership of its challenges and responses.

“This means learning from others in similar situations: what has worked, what has failed, and what can inspire approaches in countries such as Kenya or Nigeria. The focus must remain on developing solutions suited to our context,” she said.

The event titled, Beyond Aid Dependency: Unlocking Domestic Health Financing Through Health Taxes, gathered health economists, government officials, and policy experts to examine how sin taxes from tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages can improve public health while generating tax revenue.

Edwin Macharia, Global Managing Partner and co-founder of Axum, said donors mostly fund infectious diseases to curb “exporting them to their countries” while leaving the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) to African governments.

Fiscal pressures, changing patterns of disease and shrinking aid flows affect all of us

The situation has been worsened by the withdrawal of USAID, meaning “the era of relying on external funding is over,” warned Macharia, adding that “This dramatic retreat by bilateral partners has forced African governments to confront an uncomfortable reality: they must find domestic solutions to finance their health systems.”

Vivianne Ihekweazu, Managing Director of Nigeria Health Watch, emphasised the regional nature of the challenge. “The issues we are grappling with do not stop at national borders. Fiscal pressures, changing patterns of disease, shrinking aid flows, and the movement of health workers affect all of us,” she said, adding that cross-border learning is essential because solutions are most effective when countries share experiences.

Health taxes provide a “triple benefit”: they improve public health by reducing use of harmful products, raise government revenue for key projects, and ease the burden on overloaded health systems.

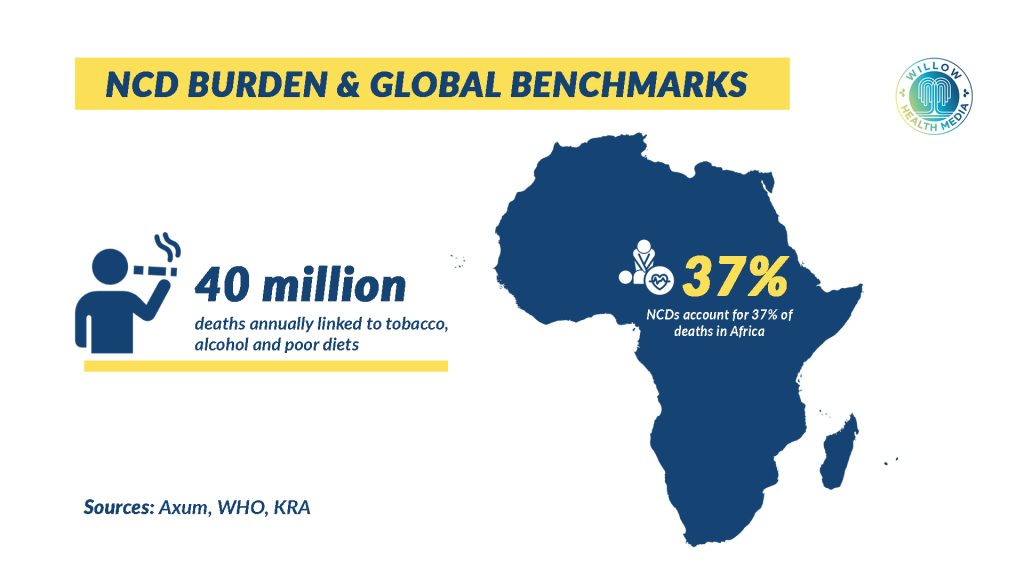

Data presented by Jonathan Munge, Project Manager at Axum, showed that non-communicable diseases (NCDs) account for 37 per cent of deaths in Africa, with 40 million people dying annually from conditions linked to tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy diets.

Evidence from countries like South Africa and Mexico shows that well-designed health taxes reduce consumption of harmful products and increase public revenue. Munge, however, noted that in Russia, for example, higher alcohol taxes cut consumption, but a later tax cut led to a sharp rise in alcohol-related deaths.

Tobacco taxes should make up 75 per cent of retail price, but only Mauritius and Morocco meet this goal

Significant gaps remain in Africa’s health taxes. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that tobacco taxes make up 75 per cent of the retail price. Currently, only Mauritius and Morocco meet this goal. The continental average is just 41 per cent, with six countries, including Angola and Zambia, imposing rates below 25 per cent.

Even Kenya, considered a regional leader, falls short. Its tobacco tax is 34.1 per cent. While Kenya’s sugar-sweetened beverage tax of 25.2 per cent is above the African average of 21.8 per cent, there is still room for progress.

“These sin goods continue to undermine health conditions in Nigeria,” said Dr Olumide Okunola, Health Specialist at the World Bank. “The revenue from taxing such products is substantial and can bridge funding gaps once filled by developed countries.”

Dr Taiwo Oyedele, Chairman of Nigeria’s Presidential Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms Committee, acknowledged the complexity of the issue as “Taxing these products is not a simple solution. Millions depend on this value chain for livelihoods, from retailers to vendors and suppliers. Policymaking must balance health priorities with economic realities.”

Nigeria is pioneering a new approach by taxing drinks based on their pure alcohol content, not their volume, with Dr Oyedele explaining that under this new system, they easily realised that spirits were being “significantly undertaxed.”

Reducing consumption of beer, tobacco and sugary drinks results in declining tax revenues

Macharia, however, underscored the political alignment needed to push sin taxes, as taxpayer morale has to be considered and

“For progress, the underlying political drivers must be understood and addressed.”

Dr Sultani Matendechero, Deputy Director at Kenya’s Ministry of Health, urged for the reframing of “Sin taxes not from the perspective of revenue generation but from the perspective of a public health intervention” by making access to these products so punitive that the consumption dwindles.

But this health-centred framework exposes a built-in trade-off: reducing consumption results in declining tax revenues, but the money raised as a “side effect” should be “ring-fenced as a compensatory fund or contribution to deal with the effects of these items or other healthcare public health problems.”

Potential pitfalls of successful sin taxes on beer and tobacco include people taking to local brews like chang’aa or smoking kiraiko (unprocessed tobacco), warned Dr Matendechero , arguing “These alternatives pose even a bigger danger than what they are stopping to smoke.”

The Kenyan experience with tobacco illustrates another challenge to the market with the introduction of nicotine pouches and vaping devices, added Dr Matendechero, adding. “We will have to quickly be fluid enough to also bring those alternatives into the dragnet so that they can also be taxed.”

Ghana allocates 2.5 per cent of its national Value Added Tax to its health insurance scheme

Lydia Otieno from the Kenya Revenue Authority’s Customs division reported that Kenya collected Ksh68 billion in excise duty from these products in the 2022-2023 financial year, rising to 73.6 billion in 2023-2024, an 8.1 per cent increase. However, she acknowledged the threat posed by illicit trade.

“To avoid certain big jumps that create a strong incentive for smuggling,” Otieno said, authorities must “increase taxes gradually” while implementing “secure tax stamps as well as track and trace systems” and “strengthen border and customs enforcement.”

Several African countries are “earmarking” health tax money to specific programmes, with Ghana allocating 2.5 per cent of its national Value Added Tax to its health insurance scheme, covering 90 per cent of its budget. Similarly, South Africa dedicates 14 per cent of its health budget to HIV/AIDS and TB programmes.

Dr Abubakar Kurfi of Nigeria’s National Health Insurance Authority noted that the country could direct tax revenues toward universal health coverage (UHC). However, this approach has trade-offs. It can make spending more accountable and shield health funds from other budget needs. But it can also make government spending rigid and reduce financial flexibility during an economic crisis.

Dr Okunola pointed to the Philippines, where sin taxes bankroll UHC, with the transparency being crucial to maintaining public and political support for health taxes.

When alcohol prices go up, the wealthy switch brands or move from an 18-year-old whiskey to a 12-year-old

A key question arose: Do sin taxes hurt the poor more than the rich? According to Dr Matiko Riro, Associate Director, Health Financing at Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), argued that the impact depends on several factors, especially substitution.

“When whiskey prices go up,” he explained, “wealthier people simply switch brands or move from an 18-year-old whiskey to a 12-year-old. The poor can’t do that. They have fewer options, so the burden hits them harder.”

Dr Oyedele said a country’s economic context matters as “In Europe and the US, low inflation means a 20 per cent tax can change behaviour. In many African countries, that’s just normal annual inflation, so consumption barely changes.”

In Africa, even without tax hikes, manufacturers often raise prices by over 100 per cent, and demand stays stable, showing strong price inelasticity.

He stressed that governments must balance public health goals with the livelihoods of workers across the supply chain and pair taxes with education and behaviour-change efforts. He also noted the importance of sustainable financing and “complementary interventions including education, behavioural changes, and social issues.”

Macharia posed the accountability question of how sin tax revenue is used, considering it represents a promising but complex tool requiring careful policy design, political courage, transparency in revenue use, and constant vigilance against unintended consequences.

With foreign aid declining and disease burdens rising, African countries must find sustainable ways to finance their health systems.

Health taxes may not be a panacea, but as Dr Korir reminded the gathering, the responsibility for solving these challenges rests squarely on African shoulders, and that means trying every viable option available.