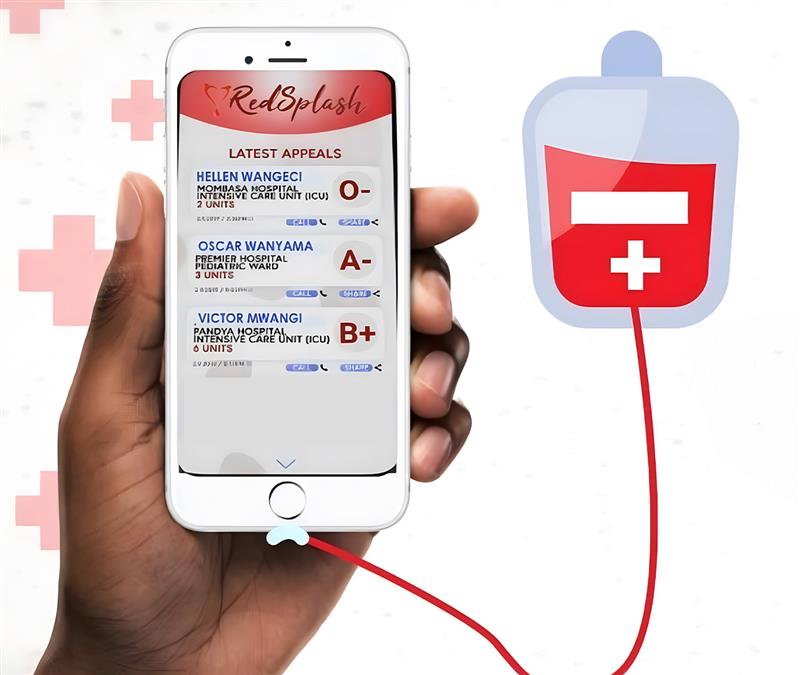

The Red Splash app works like a digital matchmaker, using a smart donor algorithm to connect someone who needs blood with the person who can give it.

Khadija Mohammed Juma uses her phone to coordinate blood donations because Red Splash, the organisation she founded, doesn’t have an official number. Her phone rings constantly-patients, families, and friends desperately seeking donors.

Khadija, the head of immunisation at Tudor Sub-County Hospital in Mvita, Mombasa County, started Red Splash in 2019 after losing a close friend’s mother who couldn’t get a blood transfusion on time due to cartels and obstructions.

“It pains me when someone loses a parent or loved one and there is something you can do, especially give blood, which is supposed to be free,” says Khadija, who was recently nominated for the Aster Guardians Nursing Awards, which honour exceptional nurses globally. Though she didn’t win, the nomination validated her work’s impact.

And the figures are telling: Kenya needs about 500,000 units of blood annually, but collects only around 200,000 to 250,000 units, leaving a critical shortage. African countries collect only 5.2 units of blood for every 1,000 people, below the ten donations or more per 1,000 people recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

“Fear and misconception about blood donation are the biggest challenges,” Khadija explains. In Mombasa County, people avoid donating due to cultural myths and misconceptions.

Fears over infertility, permanent weakness, and spiritual taboos deter blood donation

A 2021 study by the Kenya National Blood Transfusion Service and the Ministry of Health titled Barriers to Voluntary Blood Donation in Kenya corroborates her fears, finding widespread concerns about infertility, permanent weakness, and spiritual taboos that deter blood donation. The report also identified cartels and brokers within the system as major barriers.

“People start looking for blood when there’s already a need, which is too late. Instead, we should have a culture where people donate regularly, so blood waits for the patient—not the patient for blood,” she emphasises.

The country’s voluntary blood donation rate stands at four to six donations per 1,000 people, far below the WHO’s estimate that blood donation by 1 per cent of the population is generally the minimum needed to meet a nation’s most basic requirements. Seven out of ten blood transfusions rely on family or friends, not volunteer donors.

A 2022 performance audit by the Office of the Auditor General showed the Nyeri Satellite Centre collected only 9,592 units annually between 2016/2017 and 2018/2019, 33 per cent below its 14,400-unit target.

Red Splash uses a phone app with a smart donor algorithm to match patients with donors. However, Khadija’s approach extends beyond digital solutions, as her team organises blood drives at youth-centred festivals featuring games, music, and competitions.

We don’t handle blood directly; all of it goes to the blood bank, says Khadija

“Youth are our largest target donors,” she says. “These fun activities have made some of our most successful blood drives possible.”

Since 2019, Red Splash has conducted over 500 blood drives, collecting more than 75,000 pints of blood. With each pint typically separated into three components, every donation can save multiple lives. The organisation has registered about 3,000 regular donors.

Red Splash works with the Kenya Tissue and Transplant Authority (KTTA), which provides blood bags, donor beds, and storage services. Well-wishers supply water, snacks, and drinks for donors and volunteers.

However, mobile apps like Red Splash aren’t legally recognised by KTTA. A study by researcher Catherine Mwangi shows these digital platforms remain underutilised, not due to a lack of donors, but because they aren’t integrated into the national system.

“We don’t handle blood directly; all of it goes to the blood bank. But the existing policies don’t accommodate apps like Red Splash, and that needs to change,” Khadija insists.

We rely on well-wishers, and when no one chips in, I fund activities from my own pocket

The Kenya Human Tissue and Organ Transplant Bill (2024), which could formalise blood donation regulations, remains pending in Parliament. This legislative gap enables unregulated practices and blocks the integration of grassroots innovations.

As a non-profit, Red Splash operates on limited resources. “We rely on volunteers and well-wishers. Sometimes when no one chips in, I fund activities from my own pocket,” Khadija admits.

Organising drives outside urban areas presents logistical difficulties. She dreams of acquiring a mobile blood donation unit to reach rural areas in counties like Kwale and Kilifi.

For every 1,000 blood donations, around 50 units test positive for serious infections like HIV or hepatitis, highlighting safety concerns.

The WHO African Region Status Report on Blood Availability, Safety, and Quality in 2022 noted that nearly half the blood units needed to meet the WHO’s targets remain unmet across the continent.

Every blood drive, donor registration, and patient-assisted show what community-driven innovation can achieve within a strained healthcare system. Khadija’s work continues despite policy gaps and system inefficiencies.

As she prepares to return to immunisation duties, her phone rings again—another family seeking a donor. She answers promptly, knowing that behind every request is a life that might depend on her response. “With the right policies and goodwill, no one should have to beg or pay for blood,” she says with resolve. “Saving lives one drop of blood at a time, that’s what keeps me going.”

Her vision is clear: a future where blood flows freely to those in need—no brokers, no cartels, just humanity.