A single tap, a team of mothers, and one woman’s vision feeds now keeps over 600,000 children in 1,500 Kenyan schools daily.

What started as a corrugated iron sheet (mabati) structure feeding about 25 children from a church in 2012 has morphed into the largest kitchen in East and Central Africa.

When Wawira Njiru, a nutritionist, started out, word went round and the first bunch increased to “Thirty and then 35, the list just gets longer and longer,” she recalls.

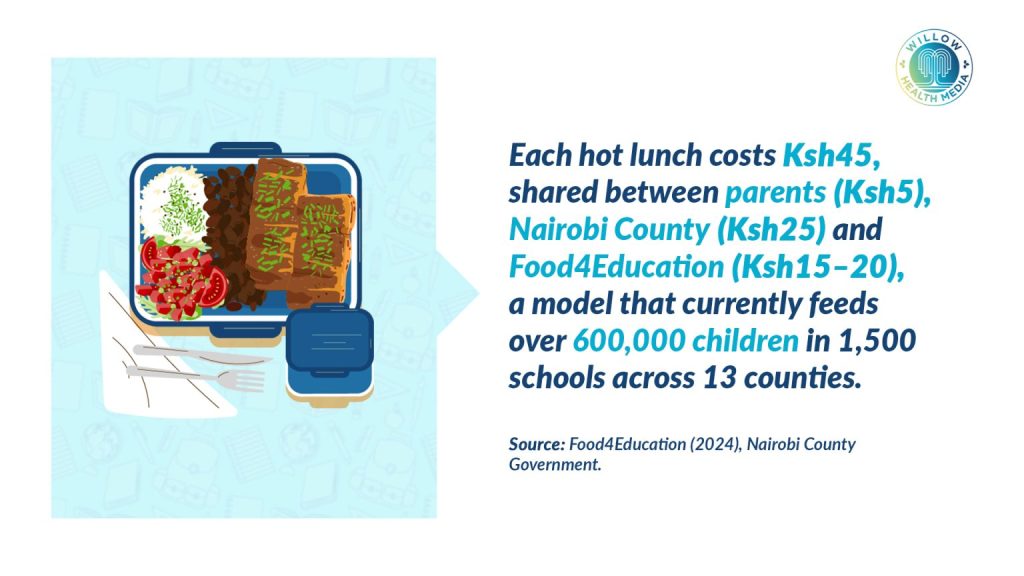

Shortly, the mathematics of need were overwhelming, but Wawira didn’t imagine it would grow into Food4Education, a school feeding project that now keeps over 600,000 needy children in school for as little as KSh45 daily; a bill shared between parents, county governments and donors.

All a student does is tap a silicon wristband on a reader at lunchtime to unlock a meal.

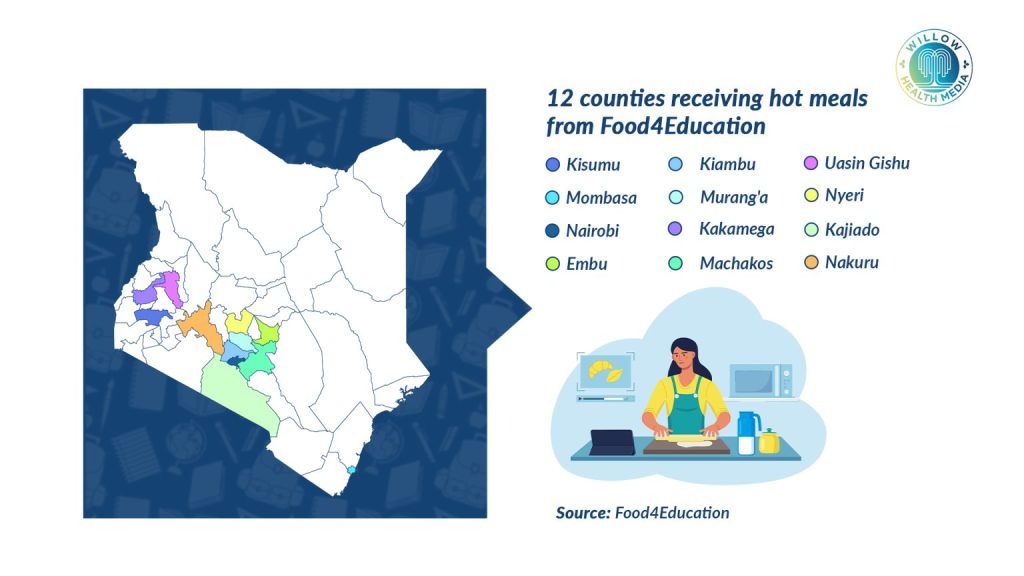

Food4Education now has served over 150 million meals in 1,500 schools across 13 counties; a feat achieved from 2015 when Wawira was inspired by India’s strategically located central kitchens that distribute meals to surrounding schools.

The project is a far cry from the initial smoke, sweat

Wawira saw the blueprint for scale: She launched the “44 Plates” campaign, raised funds and built Food4Education’s first central kitchen in 2016 with 25 meals steadily increasing to 300.

Today, the gleaming stainless steel kitchens and digital tracking systems are a far cry from the initial smoke, sweat, and struggle.

Agnes Wambui, the first employee, has seen Food4Education move from firewood to precision cooking technology.

“We used to cook with firewood. Sometimes it wasn’t dry,” she explains, her voice carrying the weight of those early mornings. “We had to prepare the food on time, but the means of cooking were very low.”

The work was gruelling and involved cooking, preparing, loading, serving and even handling cash payments as digital wristbands were still a rumour.

Food is dispatched from the kitchen at temperatures above 80°C

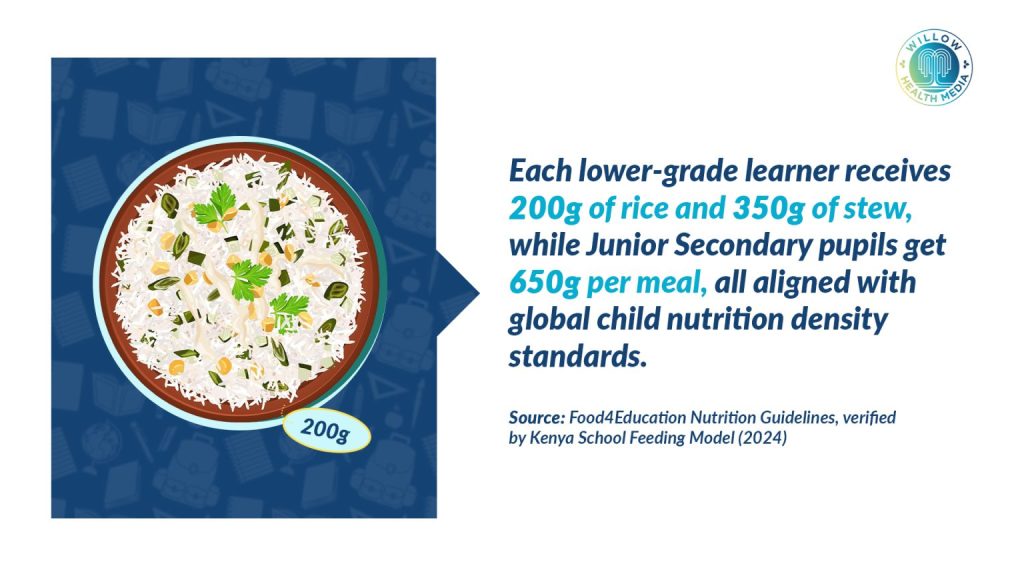

Caroline Kinuthia, a Kitchen Manager, explains how “food is dispatched from the kitchen at temperatures above 80°C” and served in schools above 65°C.

Nancy Mwangi, Team Lead at the Giga Kitchen, oversees thermal tracking so that “The child will be safe eating this food.”

But temperature is just one variable. In the laboratory, Daniel Makwata conducts what he calls “intermediate quality checks.” Every ingredient, every container, every utensil undergoes microbiological testing according to a comprehensive monthly plan.

“The water, the food itself, the delivery containers, the scoops, the jugs, the cooking vessels, we analyse all those samples,” Makwata explains. “Kitchen staff have food handler certificates, but we verify they’re maintaining good hygiene practices.”

No more delayed lessons, lost money, theft among students

The Tap2Eat system provides real-time data on feeding numbers at each school, allowing the kitchen to predict patterns “and feeding trends of every specific school.”

In schools, the Tap2Eat wristband has solved multiple problems like delayed afternoon lessons, lost money and theft among students.

Teachers like Rosemary Wanjiru now say, “With the technology, we are very fast. It’s quite efficient and has also helped them appreciate technology.”

Teresia Nyokabi, the Customer Service Lead, manages inquiries across multiple languages and says, “We have vernacular support because we’re in so many zones,” she explains. “When parents call in, most of them don’t understand English or Swahili. So we’ve made sure every team member can speak a different language to ensure we give 360-degree support.”

The engagement tool allows communication via calls, SMS, and WhatsApp, meeting parents where they are.

Natasha Musyoki, Senior Associate for Impact, notes, “We’ve seen an increase in attendance…because there’s that promise of a meal,” she reports. “We’ve seen better concentration and learning outcomes.”

The entire Food4Education operation runs on Ksh45

Teacher Wanjiru adds that “Our learners are quite healthy. That can be seen even in the way they concentrate in class. It’s a motivation. There’s no truancy.”

She says some students on sick off “Return during lunch hour just to eat.”

The entire Food4Education operation runs on just Ksh45: “The meals, the warehouse, the trucks, everyone included is Ksh45 in that cost,” Wawira explains. This covers ingredients, preparation, quality testing, transportation, staff salaries, and overhead.

Donors cover about Ksh15 per meal. In Nairobi, where economic capacity is higher, parents contribute around Ksh25 of the remaining Ksh30, with additional support covering the final Ksh5.

Each meal keeps a child in class, a mother at work

This hybrid funding model has universal feeding. “In Nairobi, it’s the only county we feed from ECD to primary, every single child, to the end of JSS, every single child,” Wawira states.

Across Africa, only 19 per cent of children receive a guaranteed school meal daily, and Wawira is already in talks with other African governments to replicate the model from Kenya’s blueprint of addressing child hunger and educational inequality.

Each meal keeps a child in class, a mother at work, and a community on its feet.

Food4Education also employs over 4,000 Kenyans, including Winfred M’Mukiri Nkuene, a cook, who comfortably pays for children’s school fees and “I’ve managed to buy a plot.”

Virginia Wangechi Mugo, a cleaner, also no longer struggles to feed her family and says, “This job turned my life around.”

Tap, Eat, Learn: How Ksh45 daily lunch keeps 600,000 children in Kenyan schools

What began in a small church kitchen has grown into a feeding revolution powered by data, mothers, and determination.

A hot meal, a silicon wristband, and a promise that no child will learn on an empty stomach… the story of how Kenya reimagined school feeding.