Kenya is among 18 priority countries to get Lenacapavir, a revolutionary option for populations unable to adhere to daily oral pills due to stigma, forgetfulness or access issues

Scientists have created a powerful new weapon against HIV: a simple injection that protects you for six months with just two shots a year. Called Yeztugo (Lenacapavir), this breakthrough drug is 99.9 per cent effective at stopping HIV infection, according to major trials in Africa.

Developed by Gilead Sciences and approved by US regulators on June 18, 2025, Lenacapavir has been hailed as a revolutionary PrEP option, especially for populations unable to adhere to daily oral pills due to stigma, forgetfulness, or access issues in what has been hailed as ‘Breakthrough of the Year’ by Science magazine.

“This is the transformative PrEP option we’ve been waiting for,” said Dr Carlos del Rio of Emory University and explained that the two shots a year solve the big problems with daily pills – people forget to take them or face stigma, besides studies showing most people prefer fewer doses.

In October 2024, Gilead struck deals with six generic drug makers to produce cheaper versions of Lenacapavir for 120 poor countries. The company promised to sell the drug at cost price until these manufacturers can supply enough doses globally.

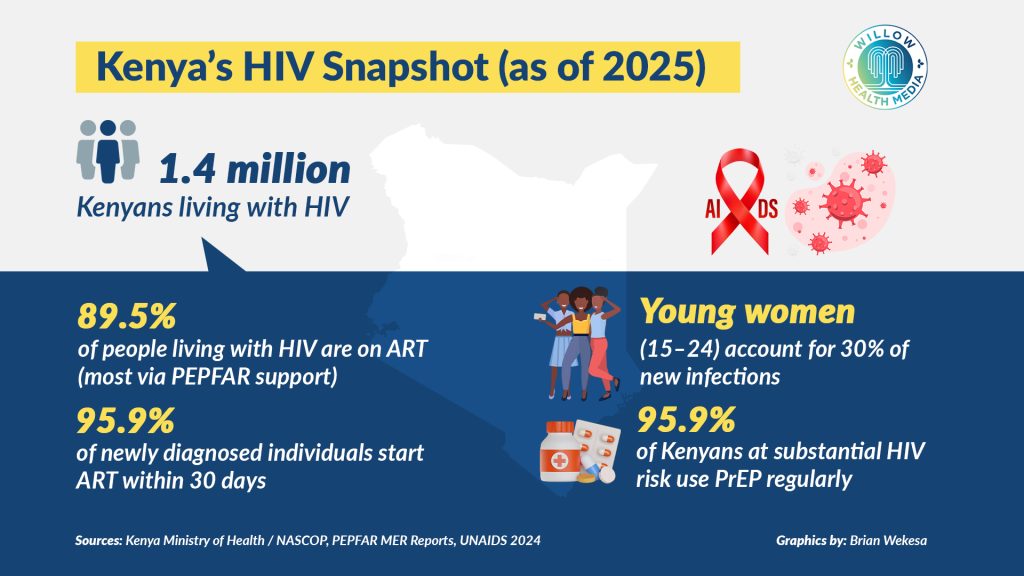

With 17,000 new infections and 21,000 AIDS-related deaths reported in Kenya in 2023 alone, the fight is far from over. Luckily, Kenya is among 18 priority countries getting the drug first for being among those that account for 70 per cent of HIV cases in eligible countries.

Gilead consulted over 100 health groups to design this rollout plan that also includes; Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, and Nigeria. Others are, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines.

Despite its promise, the price tag for Lenacapavir has raised alarm. Gilead is expected to charge about $28,218 (Ksh3.6 million) per patient annually in the US, an amount that is inaccessible for most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where HIV treatment costs on average just $75 (Ksh9,680) a year.

However, research from Dr Andrew Hill in the University of Liverpool suggests that Lenacapavir could be produced for as little as $25 (Ksh3,226) a year if manufactured generically and at scale.

The steep price tag set by Gilead has raised pressing ethical concerns around global equity with UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima arguing “If this game-changing medicine remains unaffordable, it will change nothing. I urge Gilead to do the right thing. Drop the price, expand production, and ensure the world has a shot at ending AIDS.”

Byanyima notes that Lenacapavir can be produced for just $40 per person per year, falling to $25 within a year of rollout and thus “It is beyond comprehension how Gilead can justify a price of $28,218.”

Since declaring HIV a national disaster in 1999, Kenya has made enormous strides. Prevalence dropped from 13 per cent to about 4.5 per cent, and mother-to-child transmission is at an all-time low. With support from The United States President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund, over 90 per cent of diagnosed individuals in Kenya are on antiretroviral therapy (ART), and viral suppression rates continue to rise.

Still, challenges persist especially amongst young people, key populations, and communities facing high levels of stigma. As Prof Dorothy Mbori-Ngacha, a leading paediatric HIV expert, warns, “Gen Z isn’t thinking about HIV. They are more afraid of pregnancy. But complacency is dangerous. We must keep fighting.”

The new HIV breakthrough comes in the wake of the USAID and PEPFAR funding freeze initiated by US President Donald Trump early this year. This freeze has delayed billions in aid for global health programmes and jeopardized Kenya’s HIV response.

Previously, PEPFAR supported HIV testing, treatment, Community Health Volunteer (CHV) salaries, and drug procurement in Kenya, with over 1.2 million people relying on these services. Without quick resolution, Kenya risks losing decades of progress, particularly its ability to adopt new innovations like Lenacapavir.

A PEPFAR Watch report notes that 36 per cent of program partners globally shut down within a week of funding suspension, even as UNAIDS warned that 79 per cent of recipient countries have reported major service disruptions.

As Kenya considers the rollout of Lenacapavir, the twice-yearly injectable PrEP, the big question remains: Can the health systems in remote areas support this innovation, and can the people who need it most actually access it?

Poor infrastructure, long distances, and unreliable power supply compromise storage and delivery of life-saving medicines.

A spot check on vulnerable communities within Kajiado County reveals the fragile state of healthcare service delivery. Andrew Letuyes, a Community Health Promoter (CHP), offers a sobering reminder that even the most advanced medicines are only as good as the systems that deliver them.

“When electricity goes off and there’s no backup, vaccines spoil,” he says. “Sometimes we travel 20 kilometres, only to arrive with spoilt medicine. That means many go without care.”

Letuyes also described how stigma and misinformation hinder acceptance: “People think vaccines cause some health complications. Many only agree to treatment because they trust us, not because they understand.”

He emphasized the need for cold-chain storage, transport, consistent power, and proper training. “Even airtime to call patients is a struggle. If we want to prevent disease, the system needs to work from Nairobi all the way to the most remote villages.”

Kenya stands at a crossroads. Lenacapavir represents the future of HIV prevention, but only if it is made accessible, affordable, and supported by a robust health system. To fully realize its potential, the country must assess infrastructure needs for a twice-yearly injection model.

It also needs to secure contingency funding to cover delayed donor disbursements, educate young people and at-risk groups to improve PrEP uptake and trust, and support CHPs with adequate training, logistics, and motivation.

If Kenya can rise to meet these challenges, Lenacapavir could be the final push towards achieving an AIDS-free generation by 2030.

You’re so interesting! I do not think I have read through a single thing

like that before. So wonderful to discover somebody with

genuine thoughts on this topic. Really.. many thanks for starting this up.

This website is something that is required on the internet, someone

with a bit of originality!